Sixty more satellites for SpaceX’s Starlink broadband network launched Monday on a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral, bringing the total number of Starlink platforms deployed in orbit since last May to 300.

More Starlink missions are on tap in the coming months, with the next slated to fly aboard another Falcon 9 launcher as soon as early March.

Monday’s mission began with a burst of flame from SpaceX’s Falcon 9 booster, followed by the release of hold-down clamps to allow the 1.2-million-pound Falcon 9 to climb into a partly cloudy sky over Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad.

The 229-foot-tall (70-meter) rocket lifted off at 10:05:55 a.m. EST (1505:55 GMT) powered by thrust from nine kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines.

The Falcon 9 quickly cleared lightning towers at pad 40 and steered toward the northeast, sending a window-shaking roar across the Florida spaceport.

Two-and-a-half minutes into the mission, the Falcon 9’s first stage booster shut down its engines and separated, allowing a single Merlin engine on the launcher’s second stage to fire into orbit.

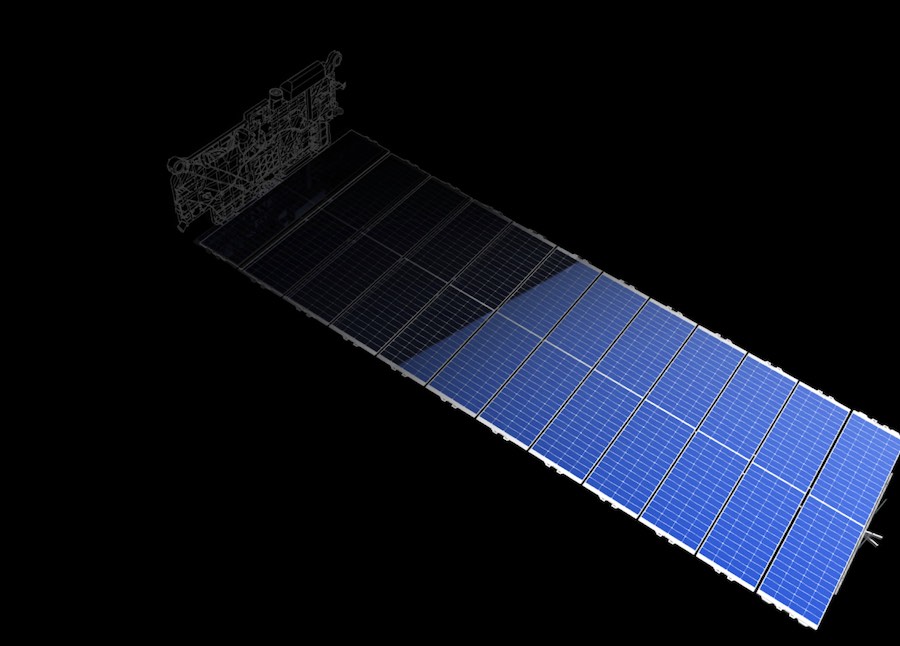

Seconds later, the Falcon 9’s payload shroud jettisoned as the rocket soared into space, revealing the launcher’s more than 34,000-pound (15.6-metric ton) payload package, comprised of 60 flat-panel signal relay nodes for SpaceX’s Starlink network.

While the second stage accelerated into orbit, the first stage of the Falcon 9 descended back through the atmosphere and attempted landing on SpaceX’s football field-sized drone ship “Of Course I Still Love You” holding position nearly 400 miles (630 kilometers) northeast of Cape Canaveral.

But the rocket missed the drone ship and appeared to make a soft landing in the water nearby, according to streaming video from the offshore vessel. The missed landing marked the first time a first stage booster on a Falcon 9 rocket has missed a landing attempt on a SpaceX drone ship since 2016.

The rocket used on Monday’s mission was a veteran of three previous launches and landings. It’s not likely to be reused after landing in sea water.

Two other SpaceX vessels were positioned in the Atlantic Ocean to try to catch the two halves of the Falcon 9’s payload shroud. SpaceX did not announce the results of the fairing recovery attempt, but a company employee said engineers are still experimenting with catching the aerodynamic shroud using fast-moving ships fitted with giant nets. Previous catch attempts have been hit or miss.

Around the same time as the first stage reached the ocean, a SpaceX launch controller announced that the Falcon 9 upper stage had arrived in orbit and was poised to release the 60 Starlink satellites, the mission’s primary objective.

After firing thrusters to enter a controlled spin, the upper stage released retention rods holding the Starlink satellites to the rocket. That allowed the spacecraft — each weighing about a quarter-ton — to fly away from the Falcon 9 as the vehicles soared over the North Atlantic Ocean.

One change introduced Monday different from past Starlink missions was the release of the Starlink payloads into an elliptical transfer orbit, instead of a circular orbit.

SpaceX did not respond to questions from Spaceflight Now on the reason for the change in launch profile, but a host on the company’s webcast Monday said all future Starlink missions will use the new trajectory to inject the satellites into an elliptical orbit after a single upper stage burn.

“We are executing a direct inject of the Starlink satellites into an elliptical, or oval-shaped, orbit,” said Jessica Anderson, a manufacturing engineer at SpaceX. “In prior Starlink missions, we deployed the satellites into a 290-kilometer (180-mile) circular orbit, which required two burns of the Merlin vacuum engine on the second stage.

“Keep in mind the stack of 60 Starlink satellites combined is one of the heaviest payloads we fly, so putting them directly into this orbit requires more vehicle performance and makes recovery more challenging,” she said. “Going forward, and starting with today, we will deploy the satellites shortly after the first burn of the second stage, putting the Starlink satellites into an elliptical orbit.

“Once checkouts are complete, the satellites will then use their on-board ion thrusters to move into their inteded orbits at an operational altitude of 550 kilometers (341 miles).”

According to preflight predictions, the Starlink craft on Monday were programmed for deployment in an elliptical, or egg-shaped, orbit ranging between 131 miles (212 kilometers) and 239 miles (386 kilometers) in altitude, with an inclination of 53 degrees to the equator.

As a result of the orbit change, the Falcon 9’s second stage remained in orbit after release the Starlink satellites Monday. It is expected to passively re-enter the atmosphere in the coming months, instead of performing a controlled de-orbit burn, as the stage did after previous Starlink launches.

Like SpaceX’s previous Starlink launches, the satellites deployed in a tight cluster. SpaceX ground teams will activate krypton ion thrusters and other systems on the satellites to maneuver them into a higher orbit, targeting an altitude of 341 miles for operational service broadcasting signals in Ku-band.

The first phase of SpaceX’s Starlink program, which aims to beam consumer broadband to customers around the world, will include 1,584 of the flat-panel satellites — including spares — in orbit 341 miles above Earth.

SpaceX has approval from the Federal Communications Commission to operate nearly 12,000 Starlink satellites in Ku-band, Ka-band and V-band frequencies, with groups of spacecraft flying at different altitudes with various orbital tilts, or inclinations.

Last year, SpaceX signaled to the International Telecommunication Union that it may seek authority to operate up to 30,000 additional broadband satellites in low Earth orbit, potentially bringing the total Starlink fleet to 42,000 platforms.

But SpaceX says the fleet’s growth will hinge on demand, and the company must launch roughly 20 more missions before completing the first phase of its Starlink network.

SpaceX also needs to test the network and begin selling the Starlink service, and work continues on user terminals to link customers on the ground with the satellite network in space. The company has not announced a price or Internet speeds for its consumer-grade service.

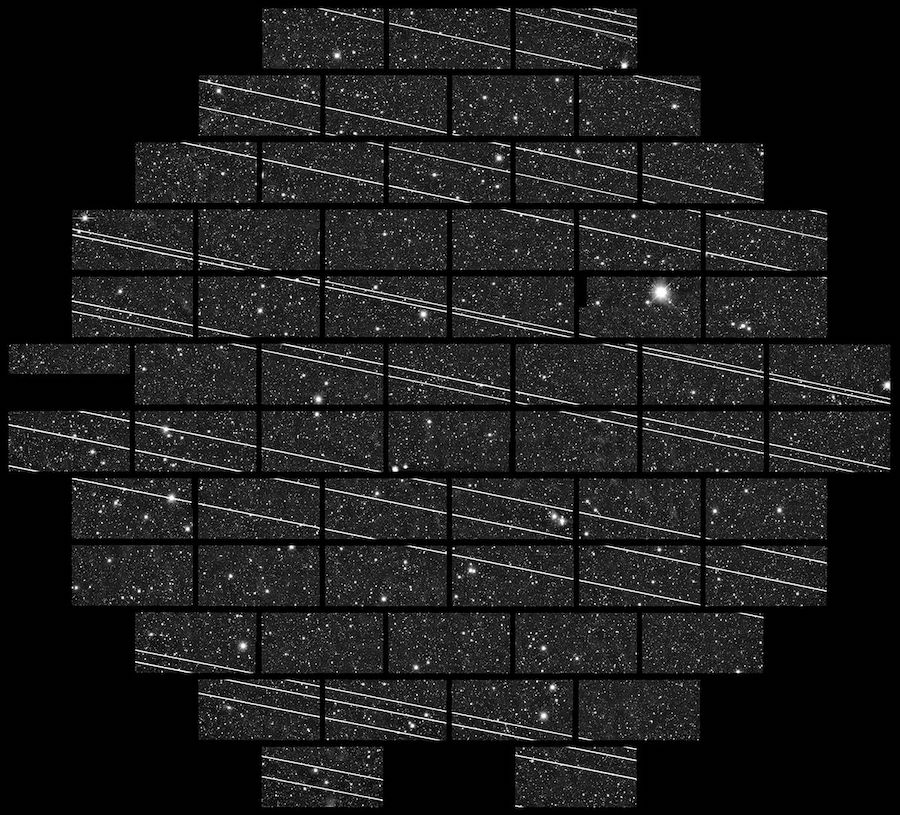

The rapid-fire deployment of Starlink satellites — coupled with plans for other large satellite fleets — has astronomers worried that the proliferation of small spacecraft could impact observations by ground-based telescopes.

The Starlink satellites are brighter than predicted, sometimes reflecting sunlight and becoming as bright as the most luminous stars in the night sky. But the brightest sightings occur only soon after a launch, when the satellites are flying at lower altitudes and are clumped close together.

The satellites are harder to spot as they spread out in the weeks after a launch and begin raising their orbits to their 341-mile-high operating altitude. But scientists caution they will pose a threat to high-power telescopes, such as the U.S. government-funded Vera C. Rubin Observatory under construction in Chile.

The International Astronomical Union — a global body chartered in 1919 to “promote and safeguard the science of astronomy” — said last week that it “considers the consequences of satellite constellations worrisome.”

“They will have a negative impact on the progress of ground-based astronomy, radio, optical and infrared, and will require diverting human and financial resources from basic research to studying and implementing mitigating measures,” the IAU said in a press release.

“A great deal of attention is also being given to the protection of the uncontaminated view of the night sky from dark places, which should be considered a non-renounceable world human heritage,” the IAU said.

At the request of the IAU, scientists from the Vera Rubin Observatory, the University of Michigan, the Centro Astronómico Hispano-Alemán, the European Southern Observatory and the European Space Agency modeled the frequency, location and brightness of satellites in planned “mega-constellations” flying in low Earth orbit.

The IAU said the results of the simulations are preliminary. Some of the simulations assumed more than 25,000 broadband satellites could be deployed in low Earth orbit, in which case between 1,500 and a few thousand spacecraft could be above the horizon at any given time, depending on the observer’s latitude.

The “vast majority” of those satellites would not be visible to the naked eye, according to the IAU. The simulations showed that around 250 to 300 of the spacecraft above the horizon at any given time would have an elevation of more than 30 degrees, the region of the sky where astronomers perform most of their observations.

At astronomical dawn and dusk — when the sun is 18 degrees below the horizon — simulations suggest around 1,000 satellites could be illuminated by sunlight and above the horizon. Around 160 of the illuminated spacecraft could be higher than 30 degrees in the sky at one time, and those are the satellites that pose the greatest threat to astronomical research.

The numbers of illuminated satellites will decrease in the middle of the night, according to the IAU.

In response to astronomers’ concerns, SpaceX launched one satellite in early January with an experimental darker coating. The long-term effectiveness of the external treatment will not be known until the satellite reaches the Starlink fleet’s operational altitude.

Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, said in December the company was in dialog with astronomers about the issue.

“Astronomy is one of a few things that gets little kids excited about space,” Shotwell said. “There are a lot of adults that get excited, too, who either depend on it for their living or for entertainment. But we want to make sure we do the right thing, to make sure little kids can look through their telescopes. It’d be cool for them to see a Starlink. I think that’s cool. But they should be looking at Saturn and the moon.”

The other company on the cusp of launching hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of broadband satellites is London-based OneWeb.

OneWeb has launched 40 satellites to date, with plans to launch roughly 32 to 36 more every month to deploy an initial fleet of nearly 650 spacecraft. But like SpaceX, OneWeb has plans to grow from there.

The satellites owned by OneWeb are smaller than the Starlink spacecraft, and they orbit higher, allowing the company to provide global coverage with fewer satellites than SpaceX. The higher altitude also means they will be dimmer to ground observers, the company says.

“We’re going to do the most we can to mitigate (astronomers’ concerns),” said Adrian Steckel, OneWeb’s CEO. “We’re not visible to the naked eye. We are visible to telescopes. It’s hard to get around some of those facts.”

Scientists have also questioned whether constellations of thousands of satellites broadcasting broadband data will interfere with radio astronomy, which uses giant antennas to listen to faint radio signals generated from distant stars and galaxies.

“With respect to radio frequency … we’ll try,” Steckel said earlier this month. “We’re going to do the most we can. I don’t know if there will be a solution that will make everybody happy. At least we’re in dialog, and we’re trying to get feedback on what can we do.”

The IAU said there is still uncertainty in the eventual impacts of huge flocks of satellites on astronomy.

“At the moment it is difficult to predict how many of the illuminated satellites will be visible to the naked eye, because of uncertainties in their actual reflectivity,” the IAU said, referencing the unknown outcome of SpaceX’s experiments with darker coatings.

“The appearance of the pristine night sky, particularly when observed from dark sites, will nevertheless be altered, because the new satellites could be significantly brighter than existing orbiting man-made objects,” the IAU said. “The interference with the uncontaminated view of the night sky will be particularly important in the regions of the sky close to the horizon and less evident at high elevation.”

The IAU said astronomical impacts during the period of time when Starlink satellites are brightest — soon after a launch — depend on how long the spacecraft are flying at lower altitudes, and the frequency of launches.

“Apart from their naked-eye visibility, it is estimated that the trails of the constellation satellites will be bright enough to saturate modern detectors on large telescopes,” the IAU concluded. “Wide-field scientific astronomical observations will therefore be severely affected. For instance, in the case of modern fast wide-field surveys, like the ones to be carried out by the Rubin Observatory (formerly known as LSST), it is estimated that up to 30 percent of the 30-second images during twilight hours will be affected.”

Formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, the Vera Rubin Observatory will capture deep, wide-field images of the entire available sky, allowing astronomers to learn more about dark energy and dark matter, and detect potentially hazardous asteroids with orbits near Earth, among other objectives.

“Instruments with a smaller field of view would be less affected,” the IAU continued. “In theory, the effects of the new satellites could be mitigated by accurately predicting their orbits and interrupting observations, when necessary, during their passage. Data processing could then be used to further ‘clean’ the resulting images. However, the large number of trails could create significant and complicated overheads to the scheduling and operation of astronomical observations.”

The IAU’s statement last week focused on optical astronomy. Astronomers continue studying the possible interference that signals transmitted by broadband satellites in low Earth orbit will have on radio astronomy.<

The IAU said there are no internationally-agreed rules of guidelines on the brightness of satellites. The group said it will present its findings to the United Nations to bring the attention of world government representatives on the issue.

“The IAU stresses that technological progress is only made possible by parallel advances in scientific knowledge,” the group said. “Satellites would neither operate nor properly communicate without essential contributions from astronomy and physics. It is in everybody’s interest to preserve and support the progress of fundamental science such as astronomy, celestial mechanics, orbital dynamics and relativity.”

SpaceX’s next launch is scheduled for 1:45 a.m. EST (0545 GMT) March 2, again from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral, when a Falcon 9 rocket will loft a Dragon cargo capsule into orbit on a resupply mission to the International Space Station.

Another Starlink launch on a Falcon 9 rocket is also scheduled as soon as March 4 from nearby pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.