A NASA authorization bill released by the House Science Committee Friday proposes major changes to the direction of the agency’s human spaceflight programs, with a goal to land crews on the moon by 2028, not the 2024 schedule set by the Trump administration.

The House version for NASA Authorization Act of 2020, which would set NASA policy if enacted into law, calls for the space agency to develop plans for sending a crewed mission to orbit Mars by 2033.

The bipartisan legislation would appear to stand in the way of any plans to build a permanently-occupied moon base or develop methods to mine water ice inside craters at the moon’s poles, which could be converted into breathing oxygen, drinking water and rocket fuel.

The bill was introduced Friday by the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology, and is cosponsored by the committee’s top Democrat and ranking Republican member. The legislation must be passed by the committee, which can amend the language in the bill, before it moves on to a vote on the House floor.

“Today’s bipartisan NASA Authorization Act of 2020 is the product of hearings, testimony, and careful work to set up NASA and our nation’s civil space program for success,” said Rep. Kendra Horn, D-Oklahoma, chair of the space and aeronautics subcommittee of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology.

“Space should not be a partisan issue, and I am proud of the across-the-aisle teamwork which made this legislation possible,” she said in a statement. “Americans should be the first to set foot on the red planet, and (this act) moves us closer to that goal by directing a steady and sustainable course of action.”

The Senate version of the NASA authorization bill passed in the Senate Commerce Committee in November, and is awaiting a vote on the Senate floor. The Senate bill does not set a schedule target for a human landing on the moon — the first since 1972 — but senators said the legislation was intended to support the Trump administration’s goal of a crewed return to the lunar surface in 2024.

NASA was targeting the 2028 timeframe for a human landing on the moon before Vice President Mike Pence announced 2024 as the goal in a speech in March 2019.

The most recent NASA authorization act was enacted into law in 2017.

The proposed House authorization act would direct NASA to develop a human-rated lunar lander in a government-run development program to launch on an upgraded version of the Space Launch System, NASA’s heavy-lift rocket designed to launch astronauts into deep space on the Orion crew capsule.

The Senate version of the authorization act supports developing human-rated lunar landers through public-private commercial agreements between NASA and industry.

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation, an organization that advocates for the commercial space industry, criticized the House authorization bill.

“As written, the NASA authorization bill would not create a sustainable space exploration architecture and would instead set NASA up for failure by eliminating commercial participation and competition in key programs,” the CSF said in a statement. “As NASA and the White House have repeatedly stated, any sustainable space exploration effort must bring together the best of government and commercial industry to achieve a safe and affordable 21st century space enterprise. We look forward to working with members of the House Space Subcommittee to address a number of concerns with the bill.”

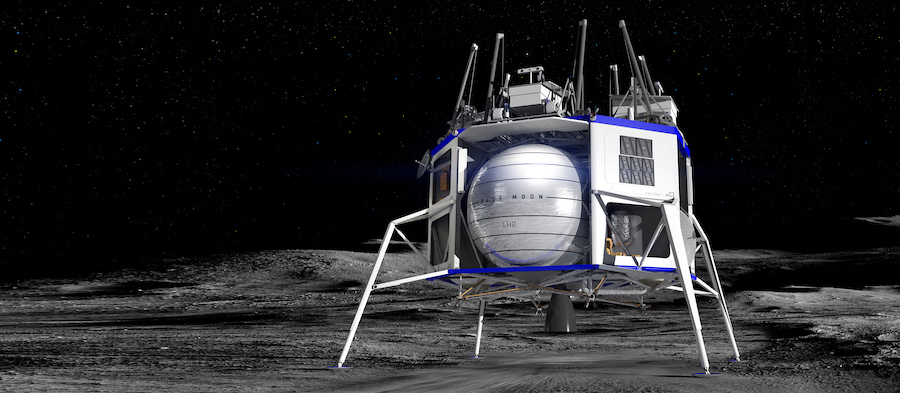

NASA is currently pursuing development of commercial human landers that can launch on commercial rockets, part of the agency’s emphasis on cost-sharing partnerships NASA officials say will reduce government expenditures and foster a growing market in the private space sector. Under that architecture, commercial rockets could launch individual elements of a lander — such as ascent, descent and transfer stage — and the modules could be robotically assembled at the Gateway, a mini-space station NASA plans to construct in a high elliptical lunar orbit.

For crewed missions to the lunar surface, NASA currently plans to purchases services from the commercial owners of the landers. Under the House bill, the government would retain ownership of the lunar landing craft.

The space agency’s Artemis program, named for the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology, aims to land the first woman and next man on the moon in 2024.

The House bill also calls for the construction of a “Gateway to Mars” in cis-lunar space — a region in the vicinity of the moon — but lawmakers write in the the authorization bill that the Gateway shall not be required for human lunar landing missions. House lawmakers want the Gateway, which would be tended by astronauts on an intermittent basis, to serve as a technological testbed for systems needed to transport crews to and from Mars.

NASA is already developing the Gateway. While NASA says it will not require commercial lunar landers to use the Gateway as a staging point for the agency’s first planned crewed landing mission in 2024, the long-term Artemis program architecture foresees the Gateway as a waypoint for transit between Earth and the lunar surface.

Lawmakers in the House want NASA to create a “Moon to Mars” program office with an objective of landing humans on Mars “in a sustainable manner as soon as practicable,” according to the text of the authorization bill. The proposed legislation in the House does not mention the Artemis program by name, but Artemis has numerous references in the Senate bill.

“The NASA Authorization Act of 2020 supports the (Trump) administration’s bold space exploration goal to return to the moon and go on to Mars while maintaining NASA’s other important science and aeronautics work,” Rep. Brian Babin, R-Texas, ranking member on the House space and aeronautics subcommittee.”

The House bill also would extend U.S. government support for the International Space Station from 2024 to 2028. The Senate authorization act calls for an extension of the space station’s life to 2030.

“The bill ensures continuity of purpose for major programs like the Space Launch System, Orion, Gateway, and Commercial Crew; directs development of a Human Landing System; and ensures continued operations of the International Space Station to at least 2028,” Babin said in a statement.

NASA should conduct precursor crewed missions to the moon to reduce risks for eventual human missions to Mars through development and testing of systems and techniques necessary for a crewed expedition to the Red Planet, lawmakers wrote in the House bill.

The text of the House bill specifically identifies plans for a permanent lunar base and utilizing lunar resources, such as water ice, as non-essential elements for the initial crewed missions to orbit and land on Mars.

Besides the rejection of the Trump administration’s 2024 target for a crewed landing on the moon, one of the biggest changes to NASA’s strategy proposed by the House authorization bill is a shift from procuring commercial lunar landers to backing a government-run lander development program.

Lawmakers on the House Science Committee wrote that NASA shall “employ an architecture that utilizes the Orion vehicle and an integrated lunar landing system carried on an Exploration Upper Stage-enhanced Space Launch System for the human lunar lander missions.”

The committee wrote that NASA should pursue the integrated, government-owned lander approach “to reduce risk and complexity and make maximum use of taxpayer investments to date.”

The Exploration Upper Stage is an enlarged second stage for the SLS rocket. The SLS Block 1B configuration will debut the enhanced four-engine upper stage to replace a single-engine unit on the Block 1 variant.

NASA says the Exploration Upper Stage is necessary to launch an Orion crew capsule and a heavy cargo on the same mission, and NASA dialed back funding for the new upper stage in recent years to focus on building the SLS core stage, which ran into years of delays due to manufacturing difficulties.

Boeing is NASA’s lead contractor on the SLS core stage and the Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS, and the company expects to ramp up work on the EUS this year after completing assembly of the SLS core stage for the huge rocket’s inaugural flight — an unpiloted test launch from the Kennedy Space Center scheduled for 2021.

Boeing is one of several industry teams that proposed a commercial human-rated lunar lander to NASA last year. The Boeing concept was the only proposal publicly disclosed that is designed to launch a fully-integrated lander on an SLS rocket without requiring a stop-over at NASA’s Gateway.

The text of the House authorization bill broadly endorses a similar architecture for a crewed lunar landing mission.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.