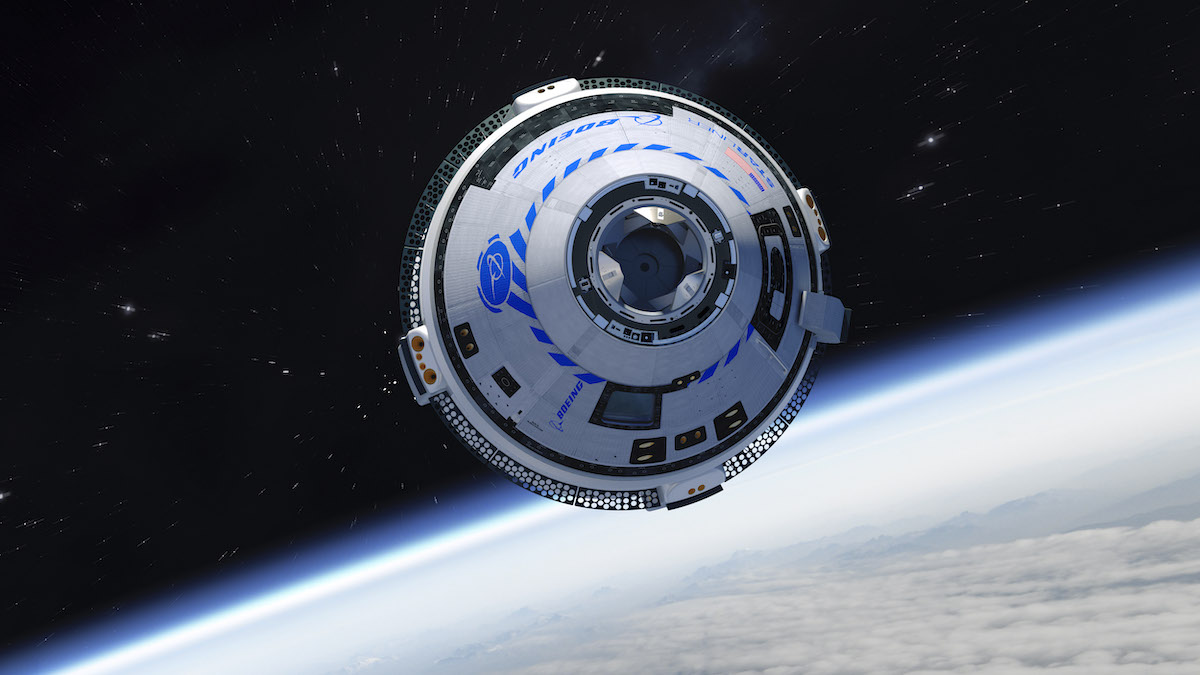

Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule flew into the wrong orbit soon after lifting off from Cape Canaveral on an unpiloted demonstration flight Friday morning, burning too much fuel and precluding the new commercial spaceship from docking with the International Space Station.

Mission managers say the capsule will target an early landing in New Mexico Sunday, bringing Boeing’s Starliner Orbital Flight Test to a premature conclusion.

The human-rated space taxi, developed through a multibillion-dollar contract with NASA, was supposed to link up with the space station Saturday on a shakedown mission before U.S. astronauts are cleared to fly on the next Starliner mission in 2020.

But the Starliner could not complete an automated orbit insertion maneuver a half-hour after launch from Cape Canaveral due to a timing error on the spacecraft, NASA and Boeing officials said. A brief interruption in communication with the capsule through NASA’s network of tracking and data relay satellites derailed an attempt by mission control to override Starliner’s autopilot and command the burn from the ground.

The ship’s failure to dock with the space station will leave some of the mission’s critical objectives unaccomplished, dealing a setback to NASA’s goal to resume launching astronauts from U.S. soil for the first time since the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

“We did have obviously some challenges today,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a post-launch press conference at the Kennedy Space Center. “When the spacecraft separated from the launch vehicle, we did not get the orbital insertion burn that we were hoping for.”

The Starliner later performed a maneuver to reach a stable, but unplanned orbit that will allow the capsule to safely circle the Earth until the ship’s next available landing opportunity Sunday at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico.

After some initial consideration of keeping the Starliner in orbit beyond Sunday to perform additional tests, officials decided Friday afternoon to proceed with the landing Sunday at White Sands, according to Bridenstine.

Two landing opportunities are possible Sunday in New Mexican desert, one at around 8 a.m. EST (6 a.m. MST; 1300 GMT), and another at 3:50 p.m. EST (1:50 p.m. MST; 2050 GMT). As of mid-afternoon Friday, officials had not decided which landing opportunity to choose.

The Starliner timer malfunction occurred within the first hour of a planned eight-day mission, minutes after an otherwise successful launch aboard an Atlas 5 rocket.

NASA has contracts with Boeing and SpaceX to transport crews between Earth and the space station. Since 2011, the U.S. space agency has purchased seats from Russia for astronauts to travel to the space station, spending more than $80 million per round-trip ticket in recent agreements with Russia’s space agency.

New commercial crew ships developed by Boeing and SpaceX are intended to end U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz capsules for human transportation to the station. NASA signed contracts with Boeing and SpaceX in 2014 — valued at $4.2 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively — to begin flying crews into space before the end of 2017.

That schedule has been delayed more than two years. SpaceX accomplished a successful Crew Dragon test flight to the station in March, but the capsule was destroyed in an explosion during a ground test of its abort engines in April.

After introducing a fix to the cause the explosion, SpaceX is gearing up for a high-altitude launch abort test in January, and says it can be ready to fly astronauts to station soon after that.

Bridenstine said Friday it was too early to know whether the Starliner malfunction — and its inability to reach the space station — will affect NASA’s plans to fly astronauts on the next Starliner mission.

“I think it’s too early to make that assessment,” Bridenstine said.

John Mulholland, Boeing’s Starliner program manager, identified the rendezvous with the International Space Station and the verification of the Starliner’s docking system performance among the Orbital Flight Test mission objectives during a pre-launch press conference Tuesday.

But Steve Stich, deputy manager of NASA’s commercial crew program, said Friday a successful docking on the unpiloted test flight is not a prerequisite for proceeding with a crewed mission.

“Both Boeing and SpaceX proposed a mission to do an uncrewed test flight that demonstrated a docking,” Stich said. “I would not say that it’s a requirement. It’s something that is nice to have, but I wouldn’t say it’s a requirement for crewed flight.”

“We still will get to do a deorbit and entry and check out those critical pieces of the mission,” Stich said. “If you think about the critical parts of the mission for the crew, it’s launch and landing. So we’ll collect that data and we’ll understand the root cause of this problem, and then we’ll have to go see what’s the next step relative to the next mission.”

The Starliner spacecraft, with an instrumented test dummy nicknamed “Rosie” strapped in the cockpit, lifted off at 6:36:43 a.m. EST (1136:43 GMT) Friday on top of a modified United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

Upgrades to the Atlas 5, such as a dual-engine Centaur upper stage and an added aerodynamic skirt for improved stability, appeared to function as designed as the 172-foot-tall (52.4-meter) launcher arced northeast from Cape Canaveral in a spectacular dawn ascent to deliver the Starliner spacecraft on a trajectory toward the space station.

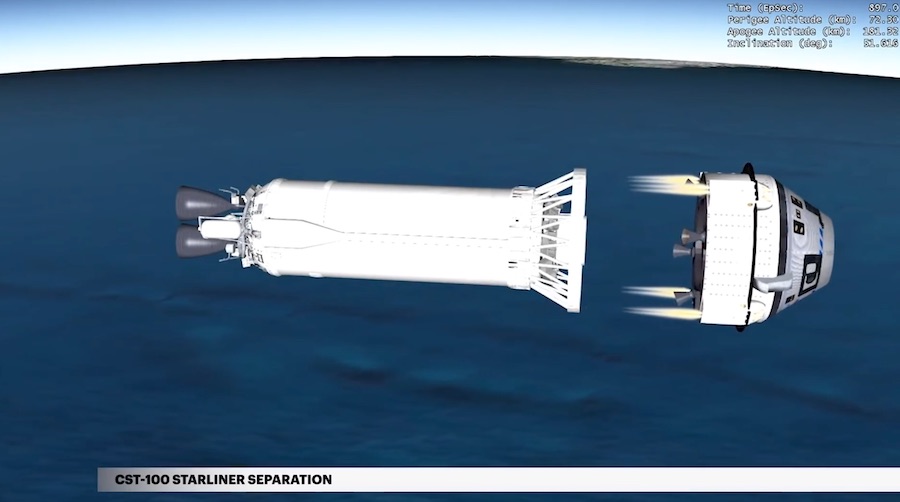

The Atlas aimed to deploy the Starliner spacecraft just shy of the velocity required to enter a stable orbit. And the rocket’s Centaur upper stage did just that, delivering the capsule on the proper suborbital trajectory and releasing Starliner to fly on its own roughly 15 minutes after liftoff.

Engineers designed the unusual Atlas 5 launch profile to limit g-forces on future Starliner astronaut crews during an abort in the event of a rocket failure.

A 40-second burn by four of the Starliner’s orbital maneuvering and attitude control engines was planned around 31 minutes into the mission. The maneuver was programmed to raise the low point, or perigee, of the Starliner’s orbit above the atmosphere, preventing the capsule from plunging back to Earth before completing a single 90-minute lap around the planet.

But a mission clock on-board the spacecraft apparently had a wrong setting, leading the ship to mistakenly believe it was operating in a different phase of its mission.

“Once the vehicle thought it was at a different time in the mission — being autonomous, a lot of this runs on a timer — it began to do burns and attitude control,” said Jim Chilton, senior vice president of Boeing’s space and launch division.

According to Bridenstine, the spacecraft consumed more propellant than anticipated as it errantly fired its control thrusters. A joint team of NASA and Boeing flight controllers in Houston noticed the problem and tried to intervene, but the Starliner did not receive their manual commands to perform the orbit insertion burn in time.

“By the time we were able to get signals up to actually command it to do the orbital insertion burn, it was a bit too late,” Bridenstine said.

Mission managers said a brief break in the satellite communication link between mission control and the Starliner spacecraft appeared to have prevented the ground commands from reaching the capsule.

In the end, Chilton said flight controllers commanded the spacecraft to maneuver into an unplanned orbit to preserve the opportunity to land the capsule as soon as Sunday morning at Boeing’s primary landing site at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico.

“The orbit we’re in today, the reason we picked it and put it there, is that allows us to return to White Sands in 48 hours,” Chilton said. “Without knowing exactly what was going on, the team quite rightly said, ‘Let me put the spacecraft in an orbit that I know I can control and get home, and give the engineering team time to thoroughly figure out whats going on.'”

Chilton said ground teams have stabilized the spacecraft after the misguided orbit insertion maneuver.

“The flight control team put the spacecraft in a safe orbit,” he said. “We’re flying tail to the sun, making sure we maximize charging (through the solar panels). All systems are good.”

The mission timer has reset, so engineers do not expect any additional problems stemming from the clock system malfunction.

Flight controllers were expected to assess later Friday what they can do to salvage some of the Starliner’s mission objectives. A pair of orbit-raising burns were planned Friday afternoon to better align for a landing opportunity at White Sands Sunday.

“We’re doing a propellant inventory management,” Chilton said. “It appears we have about 75 percent of the flight test propellant available, and the team will go figure out what subset of our overall test objectives can be achieved with the propellant remaining, while preserving a safe return to White Sands.”

In addition to the deorbit, re-entry and landing, mission planners will perform some propulsive demonstrations in orbit to exercise the spacecraft’s thrusters. Chilton said Boeing teams could test the spacecraft’s “far field,” or long distance, navigation capability and conduct checkouts of the Starliner’s optical rendezvous sensors.

There was also a chance the Starliner crew capsule could approach the vicinity of the space station for testing, officials said Friday. But that idea was apparently scrapped Friday as managers elected to proceed with a landing in New Mexico Sunday.

“We learned a lot today about the vehicle and the spacecraft,” Stich said. “This vehicle was set up to fly today the exact trajectory we’ll fly with crew on-board.”

Bridenstine suggested that if astronauts were flying on the Starliner capsule, they could have responded and taken manual control to perform the orbit insertion burn.

Boeing astronaut Chris Ferguson, a former NASA space shuttle commander, will be joined by NASA astronauts Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann on the first Starliner mission with humans on-board. Fincke and Mann joined Bridenstine and other top space officials for a press conference after Friday’s launch.

“This anomaly has to do with automation,” Bridenstine said. “Nicole and Mike are trained specifically to deal with the situation that happened today, where the automation wasn’t working according to plan. If we had crew in there, No. 1, they would have been safe … And, in fact, had they been there, we may be docking with the International Space Station tomorrow.”

“We train extensively for this type of contingency, and had we been on-board, there could have been actions that we could have taken,” said Mann, a Marine Corps fighter pilot-turned-astronaut.

Stich, a former NASA space shuttle flight director, said engineers will analyze what went wrong between the time the Starliner spacecraft separated from the Atlas 5 rocket and the programmed time of the orbital insertion burn less than 20 minutes later.

“In that critical timeframe, clearly we missed something with this timer,” Stich said. “We didn’t see it in any of the simulations … It’s in this timeframe, where the automation hands over from the launch vehicle to the spacecraft, that clearly the timer mixed up. So we’ll have to go figure out what happened, and then go solve the problem.”

Officials were not sure Friday whether the timing issue was caused by an inherent problem on the spacecraft, such as a design flaw, or something that happened on the capsule in flight.

Stich said engineers will also verify the timing issue, while resolved for now, will not crop up again during the crucial return phase of Starliner’s mission.

“The spacecraft has recovered well, and is doing well,” he said. “So we’ll work this over the next couple of days. When we look ahead, we’ll work with the Boeing team to make sure we’re safe for entry.

“We understand we had a problem with this timing with this very important insertion maneuver,” Stich said. “We’ll have to look forward and look at the deorbit burn and entry just to make sure there’s no hidden problems there. So we’ll look at the software and do some runs in the simulator … to make sure that’s all safe.”

The Starliner spacecraft is designed to return to a touchdown on land, unlike previous U.S. crew capsules, which landed at sea. Parachutes and airbags will help cushion the craft’s landing.

The Starliner setback is another black mark on a troubled year for Boeing. The company’s 737 MAX passenger jet has been grounded worldwide since March after two fatal crashes in five months, both blamed on faulty software in the plane’s flight control system.

Chilton, a veteran engineer and Boeing program manager, said the Starliner team is disappointed in the outcome of Friday’s mission.

“These are passionate people who are committing a big chunk of their lives to put Americans back in space from our soil, so it’s disappointing for us,” Chilton said. “But that doesn’t mean we’re not going to diagnose it, figure out what’s the right thing to do going forward — what kind of next flight test we fly — and keep going.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.