European Space Agency member states on Thursday committed nearly 12.5 billion euros ($13.7 billion) to fund ESA programs over the next three years, promising money to grow Europe’s fleet of satellites studying Earth’s changing climate, contribute to NASA-led lunar exploration efforts, and continue ESA’s participation in the International Space Station until 2030.

The funding approved Thursday at the conclusion of a two-day meeting of senior government representatives from ESA’s 22 member states represents a 21 percent boost over the 10.3-billion-euro three-year budget committed at the last such ministerial-level meeting in 2016.

The overall funding level closely matches ESA’s proposed budget going into the ministerial council meeting.

“You have a happy DG in front of you,” said Jan Wörner, ESA’s director general, in a press conference Thursday after the ministerial council meeting, named Space 19+, in Seville, Spain.

ESA member states will spend 12.45 billion euros ($13.7 billion) on the space agency’s programs over the next three years, nearly equaling what ESA’s leadership proposed at the start of the ministerial council meeting. The member states committed more than 1.9 billion euros ($2.1 billion) in additional funding to cover ESA’s basic activities and science program for two more years, in case there is no ministerial council meeting in 2022.

“With this conference, we’ve been able to see how strong European unity has been around this table, and how much this unity is the backbone of Europe’s strength,” said Frédérique Vidal, co-chair of the ministerial council meeting and the French minister for higher education, research and innovation. “We have made Europe a leader in space together, and together we will be able to maintain that position and enhance it still more.”

Manuel Heitor, the other co-chair of the ministerial council meeting, said the ESA budget approved Thursday represents a “consensus” among European governments. The budget marks a “further step in European competitiveness in the global space arena,” said Heitor, Portugal’s minister of science, technology and higher education.

Germany is the space agency’s largest contributor, allocating more 3.29 billion euros ($3.6 billion), or 22.9 percent of ESA’s budget, for all of ESA’s programs over the next three years, plus two additional years of money for science programs and basic activities.

France, ESA’s second-largest financial backer, committed more than 2.66 billion euros ($2.9 billion) for the same time period.

Here is a list of ESA’s five largest national contributors over the next five years:

- Germany: 3.294 billion euros ($3.6 billion)

- France: 2.664 billion euros ($2.9 billion)

- Italy: 2.282 billion euros ($2.5 billion)

- United Kingdom: 1.655 billion euros ($1.8 billion)

- Spain: 852 million euros ($938 million)

Details of the ESA budget are available in this document.

Although the overall funding level agreed at this week’s budget summit closely matched ESA’s proposal, the member states committed more money to certain segments of the space agency’s budget than expected, and less to others.

ESA will get more than 2.5 billion euros ($2.8 billion) for Earth observation programs over the next three years, including more than 1.8 billion euros (nearly $2 billion) for the Copernicus program, a fleet of Earth-observing satellites designed to track the health of our planet.

That’s a 29 percent increase over ESA’s Copernicus budget request of 1.4 billion euros ($1.5 billion).

“European Parliament has declared a climate emergency, which will mean a European reduction in carbon (emissions) of 55 percent by the year 2030, compared to the level of 1990, meaning that climate is a top priority. And Copernicus is addressing the climate question to a large extent,” said Josef Aschbacher, director of ESA’s Earth observation program.

“So I think Europe, collectively through our member states today at Space 19+, has taken its responsibility to put action to the political words which they have declared and which are being decided,” Aschbacher said.

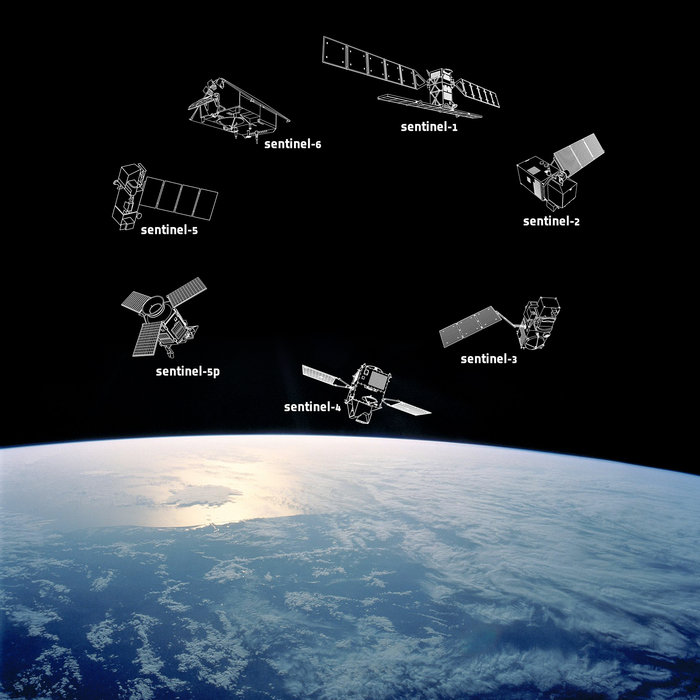

ESA is responsible for developing the space segment for the Copernicus program, including the Sentinel series of satellites and Earth-observing instruments. The program is led by the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union, a separate entity from ESA.

The additional funding will help improve the performance of future Copernicus satellites, and allow the development of new missions, such as a constellation of spacecraft to monitor carbon dioxide emissions, ESA officials said. Funding contributions to complete the next generation of Copernicus satellites will also be required from the EU.

“In short, what we are doing is a more robust and a more performing system which we are offering to the European Commission as our contribution from ESA,” Aschbacher said Thursday.

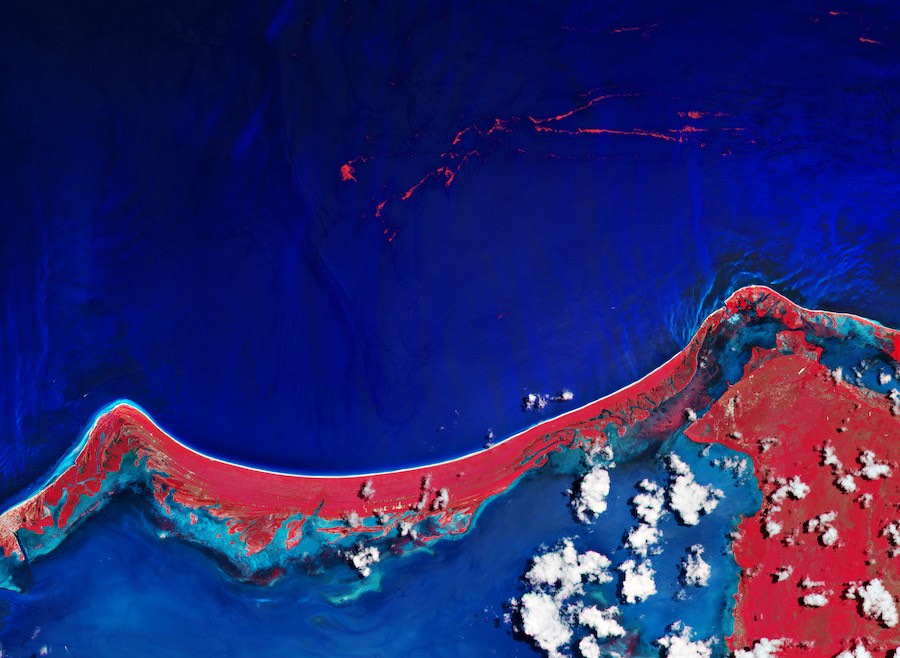

Copernicus data are distributed worldwide free of charge, supplying information for atmospheric and marine monitoring, land use surveys, climate change research and mitigation, emergency management and disaster response, and security applications.

Europe has launched seven Sentinel satellites since 2014, and plans to launch replacement craft in the early 2020s for the first pairs of Sentinel 1 radar observatories, Sentinel 2 optical satellites, and Sentinel 3 oceanography missions.

The first Sentinel 6 satellite, designed to measure changes in sea level, is scheduled to launch in November 2020, and Sentinel payloads will be hosted on the new generation of European weather satellites launching in the early 2020s to collect measurements of air pollution and atmospheric composition.

Europe’s Copernicus program is is the largest producer of Earth observation satellite data in the world. The extra funding committed in this year’s ministerial meeting will not only continue funding replacement Sentinel satellites, but will allow Europe to develop new, more advanced missions to focus on specific climate measurements.

“The most important thing maybe for us is Earth observation,” said Thomas Jarzombek, the federal government coordinator of German aerospace policy. “A lot of people out there are concerned because of climate change. It is important to understand what’s really happening in the atmosphere. Therefore, we invest hugely in Earth observation to understand better what’s happening.”

Germany is poised to benefit from its leadership in funding ESA’s Earth observation programs. ESA spreads contracts across its member states based on the size of each nation’s financial contribution.

“Everybody in every industry wants to be in the development of the top-most technology, and this is probably one of the reasons why everybody wants to be in Earth observation, because this is a place where European companies can get ahead of anyone else in the world,” said Pedro Duque, a former astronaut and Spain’s acting minister of science, innovation and universities.

A top priority for new Copernicus missions is a fleet of three satellites to monitor carbon dioxide emissions, and help scientists distinguish between CO2 emitted from human activity — called anthropogenic emissions — and natural CO2 sources.

“CO2 is a priority for Europe,” Aschbacher said. “The requirements which have been given to us by the user community … demand a much more powerful, much better-performing satellite or satellites to measure CO2.”

The new funding for the Copernicus program will help engineers improve the resolution of the CO2 monitoring satellites, allowing the carbon observatories to pinpoint CO2 sources in square grids around 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) in size. Their swaths, or viewing strips, will be increased by 50 percent to some 186 miles (300 kilometers) wide, according to Aschbacher.

“Also, we have been asked to make sure that we are distinguishing anthropogenic from natural emissions of CO2, and therefore we need three more instruments on-board to do that, auxiliary instruments we call them … All of this adds up in terms of money,” Aschbacher said. “It’s more expensive than the original configuration.”

Europe plans to launch the CO2 monitoring satellites in 2025 or 2026 to begin collecting CO2 data to gauge progress in implementing carbon reduction targets in the Paris climate agreement.

The bonus funding allocated during this week’s ministerial council summit also helps move forward other new Copernicus missions, such as a hyperspectral imaging spacecraft to support sustainable farming and other applications.

“The users consider this a very important instrument for many applications, including food security, Africa, migration and topics that are related to it, and therefore want to have it as a free flyer,” Aschbacher said. “That means you need your own platform, a launcher, the integration and all the elements connected to it. Obviously, that costs extra money, and this will be used to do that.”

ESA and the EU are also looking at several other new Copernicus missions, such as a satellite dedicated to polar sea-ice and snow snow cover measurements.

“Copernicus is now the world-leading Earth observation program,” said Wörner, ESA’s director general. “This shows that there is an awareness for our planet, and I think this is good because the taxpayers, the citizens … are asking to do something. And you can only do something if you have the right information.”

ESA commits to International Space Station until 2030, allocates funds for lunar missions

European governments this week also extended their participation in the International Space Station program until 2030, and approved further ESA contributions to the NASA-led Artemis program, which aims return astronauts to the lunar surface in the 2020s.

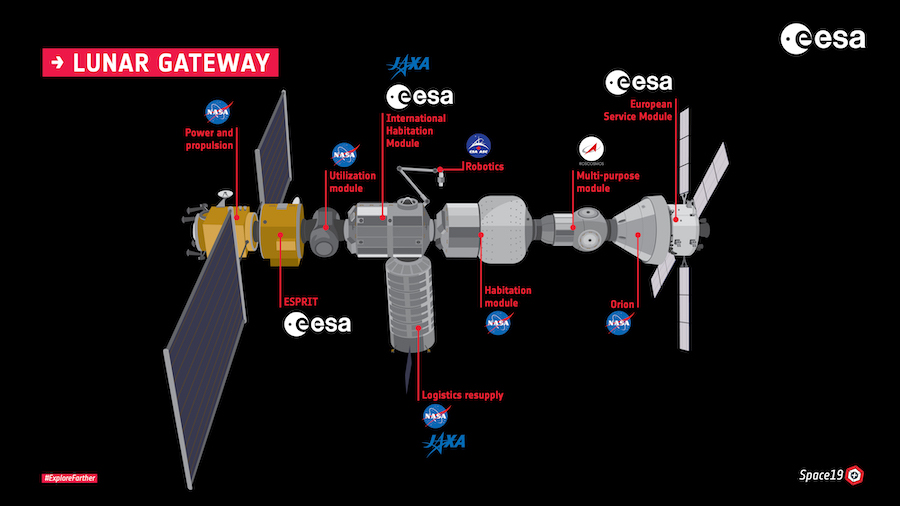

The Trump administration has charged NASA with landing astronauts on the moon before the end of 2024. The U.S. space agency is racing to meet that goal, accelerating development of a human-rated lunar lander and a mini-space station called the Gateway in orbit around the moon to serve as a waypoint and safe haven for expeditions heading to the lunar surface.

NASA has committed to the International Space Station through 2024, after which the White House has sought to end direct federal funding for the station in favor of pursuing a commercial approach to human spaceflight in low Earth orbit. But a bipartisan group of senators released a NASA authorization bill earlier this month that — if passed — would extend NASA’s commitment to the station through 2030.

With ESA’s pledge to remain in the space station program, Wörner said the agency is “ready and eager” to give each member of its 2009 class of astronauts at least two flights. So far, two of ESA’s six astronauts from the 2009 class have been assigned two missions to the station. German astronaut Alexander Gerst completed his second flight last year, and Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano is currently in orbit on his second mission.

French astronaut Thomas Pesquet is scheduled for his second expedition on the space station in 2021, and his mission will overlap with the first spaceflight by Matthias Maurer, a German astronaut who joined the ESA astronaut corps in 2015, Wörner said.

David Parker, ESA’s director of exploration, said about one-quarter of the agency’s 1.95 billion euros ($2.1 billion) budget for exploration in the next three years is earmarked for lunar missions.

“We have a program of about 300 million (euros) associated with the lunar Gateway activities, and about 150 million (euros) for lunar robotic activities, but then you have to add to that the cost of contributions to the European service modules to take humans to the moon in cooperation with NASA on the Orion program,” Parker said.

ESA wants to provide a habitation and research module for the Gateway outpost, along with an element for refueling, docking and telecommunications.

ESA member states put up money for two Orion service modules at this week’s summit in Seville. The power and propulsion modules will fly with NASA’s Orion spacecraft carrying astronauts to the moon on the Artemis 3 and Artemis 4 missions, which will lift off on top of NASA’s Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket.

European engineers have already built and delivered to NASA the first Orion service module for the unpiloted Artemis 1 test flight, and the second Orion service module is well along in construction in Germany.

Government representatives meeting in Seville also agreed to fund early development of a robotic lunar lander that could deliver cargo, experiments and supplies to the moon’s surface in support of human missions.

In a statement Thursday, ESA said it foresees the agency’s partnership with NASA to allow European astronauts to fly to the moon for the first time.

ESA also won funding to begin working on a major European contribution to a robotic mission to bring soil and rock samples from Mars back to Earth.

Working on concert with NASA, ESA would provide a fetch rover to collect sample tubes gathered by NASA’s Mars 2020 rover, which is set to launch to the red planet next year. NASA will launch the ESA fetch rover, build a lander to get it to the Martian surface, and supply a rocket to launch the samples back into space.

ESA will oversee the construction and launch of a separate spacecraft to rendezvous with the sample container in orbit around Mars and return the specimens to Earth for analysis.

A formal go-ahead on the U.S. side for a Mars sample return mission could come within months.

ESA member states also allocated funds to complete testing and launch preparations on the ExoMars rover scheduled for launch next July. But that launch schedule hinges on the satisfactory completion of parachute drop tests after the ExoMars lander’s decelerator failed in testing earlier this year.

ESA’s science program gets a boost

Member states approved a 10 percent increase to ESA’s space science budget in Seville, the most significant boost in ESA science funding in 25 years.

The science budget increase could allow ESA to move forward the launch of an ambitious European-led space-based gravitational wave observatory named LISA from 2034 to 2032. ESA plans to launch an X-ray telescope named Athena in 2031, and scientists hope to use both missions to simultaneously study the same targets, such as black holes, and help astronomers unravel new clues about high-energy physics in the distant universe.

ESA also wants to be ready to contribute to a NASA-led robotic mission to Uranus or Neptune that could launch in 2030. NASA is waiting for input from a decadal survey review by independent scientists before deciding whether to go ahead with the Uranus or Neptune mission, or prioritize another flagship interplanetary probe.

The funding hike will also enable ESA to develop a series of smaller, lower-cost space science missions to complement big-ticket projects like Athena and LISA.

A European mission named Hera will also go forward after receiving budget commitments from ESA member states.

Scheduled for launch in 2024, Hera will follow up on NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, mission after it collides with an asteroid in 2022. DART will demonstrate deflection techniques that could push a future asteroid off of a collision course with Earth.

NASA’s DART spacecraft will target a double asteroid known as Didymos. Scientists will monitor the probe’s collision with the smaller of the two Didymos objects — about the size of the Great Pyramid of Giza — to measure how the kinetic impact alters its orbit around its larger mountain-sized asteroid companion.

Hera will arrive at Didymos in 2026 and survey the aftermath of DART’s impact.

The Hera mission is part of a new space safety “pillar” of ESA’s budget proposed to the agency’s member states in Seville.

Going into this week’s ministerial council meeting, ESA’s leadership sought around 900 million euros (nearly $1 billion) for programs focused on space safety and related applications. Member states this week approved about 541 million euros ($600 million) for space safety programs.

“We did not get the overall amount, but it’s not that we’re close to suicide because we can do what we wanted to do, but some of the actions have to be a little bit delayed,” Wörner said.

For example, work to develop satellites designed to track solar storms and help predict their effects on Earth will move slower than ESA hoped. The space weather mission would include at least two spacecraft — one launched to the L1 Sun-Earth Lagrange point a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, and another launched to the L5 point, located some 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away.

The L5 location is the third point of an equilateral triangle formed with the Earth and the sun, yielding views of storms developing on the sun before they rotate to face Earth. No space weather observatory has ever flown there before.

Wörner said ESA intended to go “full speed” on the space weather mission. Instead, teams will use preliminary funding to start developing instruments for the observatory.

But other missions under the space safety segment of ESA’s budget will go ahead. Along with the Hera asteroid deflection mission, an automated space debris mitigation mission named e.Deorbit was fully funded in Seville. The e.Deorbit mission will validate technologies to rendezvous with a derelict satellite and remove it from orbit.

ESA’s telecommunication program received 1.51 billion euros ($1.6 billion) over the next three years. That represents a 30 percent increase over the telecommunications budget from the last ministerial council meeting, but 13 percent less than ESA’s request in Seville.

New priorities for ESA’s telecommunications program include development of “fully flexible satellite systems” that can be integrated with 5G networks. There’s also funding for high-speed optical communications technology development.

ESA member states allocated 2.24 billion euros ($2.5 billion) for space transportation initiatives over the next three years, including funds to improve the competitiveness of Europe’s new Ariane 6 and Vega C launchers, both scheduled for their inaugural flights in 2020.

The budget also has money to move forward with a new European “micro-launcher” to compete in the burgeoning small satellite launch market with companies like Rocket Lab and Virgin Orbit.

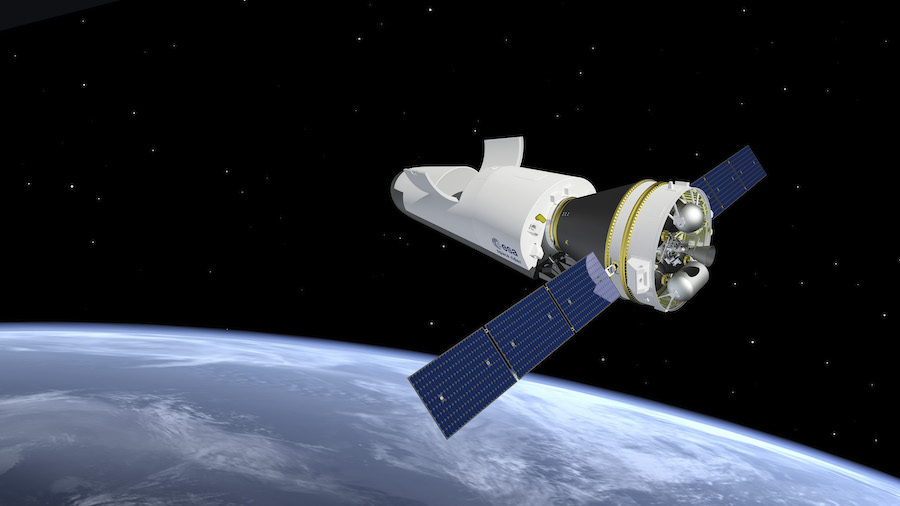

A consortium of 10 European countries, led by Italy, committed funding to complete development of a reusable spaceship named Space Rider.

Italy is funding around 75 percent of the Space Rider’s development costs. It will launch on top of a Vega C rocket, carry nearly a ton of scientific and engineering payloads into orbit, then re-enter the atmosphere and parachute into the sea for recovery and reuse on another flight.

The Space Rider has the shape of a lifting body — similar to the U.S. Air Force’s X-37B space plane — allowing it to steer close to populated islands for splashdowns at sea. The Space Rider builds on a suborbital test flight of ESA’s Intermediate Experimental Vehicle in 2015.

ESA says the Space Rider could be ready for its first flight in 2022, and is designed to operate in orbit for at least two months on each mission.

“Space Rider will not only fly, but will also land,” Wörner said. “This is very important. So we have a full-fledged space transportation program.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.