EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated Oct. 16 with SpaceX confirmation of 30,000 satellites in the ITU filings.

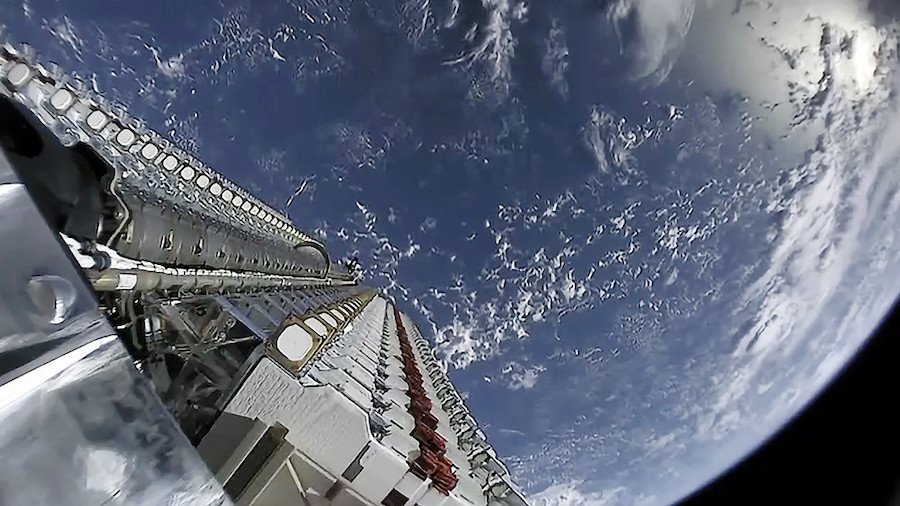

SpaceX is seeking approval to add up to 30,000 more satellites to its Starlink broadband network, on top of 12,000 spacecraft already authorized by U.S. government regulators, according to filings submitted to the International Telecommunication Union.

The Federal Communications Commission submitted documents to the ITU on Oct. 7 outlining SpaceX’s ambition to operate the 30,000 additional Starlink satellites.

First reported by Space News, SpaceX’s latest plans to expand the Starlink network would involve placing 30,000 satellites in multiple orbital planes at altitudes ranging from 203 to 360 miles (328 to 580 kilometers).

The FCC submitted 20 documents on behalf of SpaceX to the ITU as “coordination requests,” each covering SpaceX’s plans for 1,500 satellites. The ITU is an agency of the United Nations responsible for allocating international radio spectrum rights and ensuring no interference between space-based radio transmitters.

SpaceX launched the first 60 satellites for the Starlink network aboard a Falcon 9 rocket in May. Another Falcon 9 launch is scheduled to carry more Starlink nodes into orbit from Cape Canaveral in late October or November, followed by as many as 24 Starlink launches next year.

In a statement confirming the submissions to the ITU, SpaceX company highlighted increasing demand for low-latency broadband services.

“As demand escalates for fast, reliable Internet around the world, especially for those where connectivity is non-existent, too expensive or unreliable, SpaceX is taking steps to responsibly scale Starlink’s total network capacity and data density to meet the growth in users’ anticipated needs,” a SpaceX spokesperson said in a statement.

Officials said SpaceX is laying the groundwork to grow the planned total network capacity and density of the Starlink constellation up to 10 times that of earlier plans. SpaceX officials have previously stated the Starlink constellation will grow commensurate with market demand.

Basic information about the planned Starlink satellites, such as their use of steerable spot beams for customer links, is included in the ITU filings.

But the documents do not offer any details about the launch schedule for the satellites. According to ITU rules, satellite operators have seven years to launch at least one spacecraft using the requested frequencies and operate it for 90 days. At that point, the operator can receive priority rights to the requested spectrum over potential competitors.

If SpaceX intends to move ahead with the 30,000 additional satellites, the company will have to file requests for permission from the Federal Communications Commission, the government agency charged with issuing licenses to U.S.-based commercial satellite operators.

The FCC has already authorized the launch of 12,000 Starlink satellites, but SpaceX continues to adjust how it plans to deploy the spacecraft.

The initial set of Starlink satellites will fly in 341-mile-high (550-kilometer) orbits inclined 53 degrees to the equator. In August, SpaceX requested approval from the Federal Communications Commission to fly up to 1,584 Starlink satellites in 72 different orbital pathways, a change from the the commission’s earlier authorization for SpaceX to operate the same number of spacecraft in 24 planes.

The FCC has not yet ruled on that request.

SpaceX says the realignment will allow the Starlink network to begin providing broadband services to parts of the United States with fewer satellites and launches than previously planned. The Starlink fleet could offer service to the northern United States, Canada and locations at similar latitudes as soon as next year, the company said.

The Starlink network could provide coverage over all populated areas after 24 launches, SpaceX said.

Space debris experts and astronomers have raised concerns about threats posed by SpaceX’s Starlink fleet, and other satellite constellations planned by Amazon and OneWeb.

In June, SpaceX said three of the 60 satellites launched in May had stopped communicating with ground teams and will “passively” deorbit due to aerodynamic drag. SpaceX said it was purposely deorbiting two more Starlink satellites to demonstrate their capability bring spacecraft back into the atmosphere for destructive re-entries at the end of their missions.

SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk said in May that the first batch of 60 Starlink satellites were experimental, but could become part of the operational Starlink fleet after completing in-orbit tests. Each of the 60 satellites launched in May weighed around 500 pounds, or 227 kilograms, at the time of launch.

The Falcon 9 rocket that launched the first 60 Starlink satellites deployed them in a 273-mile-high (440-kilometer) orbit, where they activated electric thrusters to begin raising their altitude up to 341 miles. SpaceX previously planned to operate the initial Starlink satellites at 714 miles (1,150 kilometers), but company said the 341-mile-high operating altitude allows the spacecraft to naturally re-enter the atmosphere sooner in the event of a failure.

The European Space Agency said it maneuvered its Aeolus Earth observation satellite out of the way of one of the two Starlink satellites SpaceX was intentionally deorbiting in early September. Initial tracking data from the U.S. military suggested the descending Starlink satellite and the Aeolus spacecraft had about a 1-in-50,000 chance of hitting in orbit, which did not meet the standard industry threshold of a 1-in-10,000 chance of a collision before conducting an avoidance maneuver.

ESA and SpaceX agreed not to conduct an avoidance maneuver based on the initial probability of an impact. But further tracking data upped the chances of a collision, and ESA controllers’ email messages to SpaceX went unanswered. SpaceX said its team did not see the emails due to a computer bug in the company’s on-call paging system.

ESA finally decided on its own to fire thrusters on the Aeolus satellite to slightly adjust its course and eliminate any chance of a collision. Had it seen the email messages from ESA, SpaceX said it would have coordinated with the Aeolus ground team to determine the best approach to avoid a run-in between the two satellites.

SpaceX said it will “implement corrective actions” to resolve the glitch in communications.

“This example shows that in the absence of traffic rules and communication protocols, collision avoidance depends entirely on the pragmatism of the operators involved,” said Holger Krag, head of space safety at ESA. “Today, this negotiation is done through exchanging emails — an archaic process that is no longer viable as increasing numbers of satellites in space mean more space traffic.”

SpaceX says the Starlink satellites are equipped with automated collision avoidance systems. Using orbital tracking data uploaded from the ground, the satellites’ on-board software decides when to conduct a maneuver to avert a possible collision with another object in space.

According to ESA, there are currently around 2,000 operating satellites orbiting the Earth, and around 22,000 objects the size of a softball or larger are regularly tracked and listed in the U.S. military’s Space Surveillance Network catalog.

The launch of up to 42,000 Starlink satellites would nearly triple the catalog of space objects.

SpaceX said it also will take measures in response to astronomers’ worries about the possibility that streaks of light from passing Starlink satellites could spoil images from ground-based observatories.

Some scientists raised concerns after the first batch of 60 Starlink satellites were more reflective than expected, especially in the first few days after their launch, when they were flying at lower altitudes and clumped together in relatively close proximity.

The Royal Astronomical Society said in June that the large number of broadband satellites proposed by SpaceX, Amazon, OneWeb and Telesat “presents a challenge to ground-based astronomy.”

“The deployed networks could make it much harder to obtain images of the sky without the streaks associated with satellites, and thus compromise astronomical research,” the society said in a statement.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory, funded by the National Science Foundation, said in May it was working with SpaceX to “jointly analyze and minimize any potential impacts” on astronomical observations caused by radio transmissions coming from the Starlink satellites.

“These discussions have been fruitful and are providing valuable guidelines that could be considered by other such systems as well,” the NRAO said in a statement. “To date, SpaceX has demonstrated their respect for our concerns and their support for astronomy.”

The NRAO said it continued to monitor, analyze and discuss the “evolving parameters” of the Starlink system. The NRAO identified several proposals under consideration, including exclusion zones and other mitigations around the National Science Foundation’s current and future radio astronomy facilities.

In an effort to mitigate the concerns of optical astronomers, SpaceX plans to make the base of future Starlink satellites black, a change that is expected to reduce their brightness at dawn and dusk.

SpaceX says it will adjust Starlink orbits should it be necessary for extremely sensitive space science observations.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.