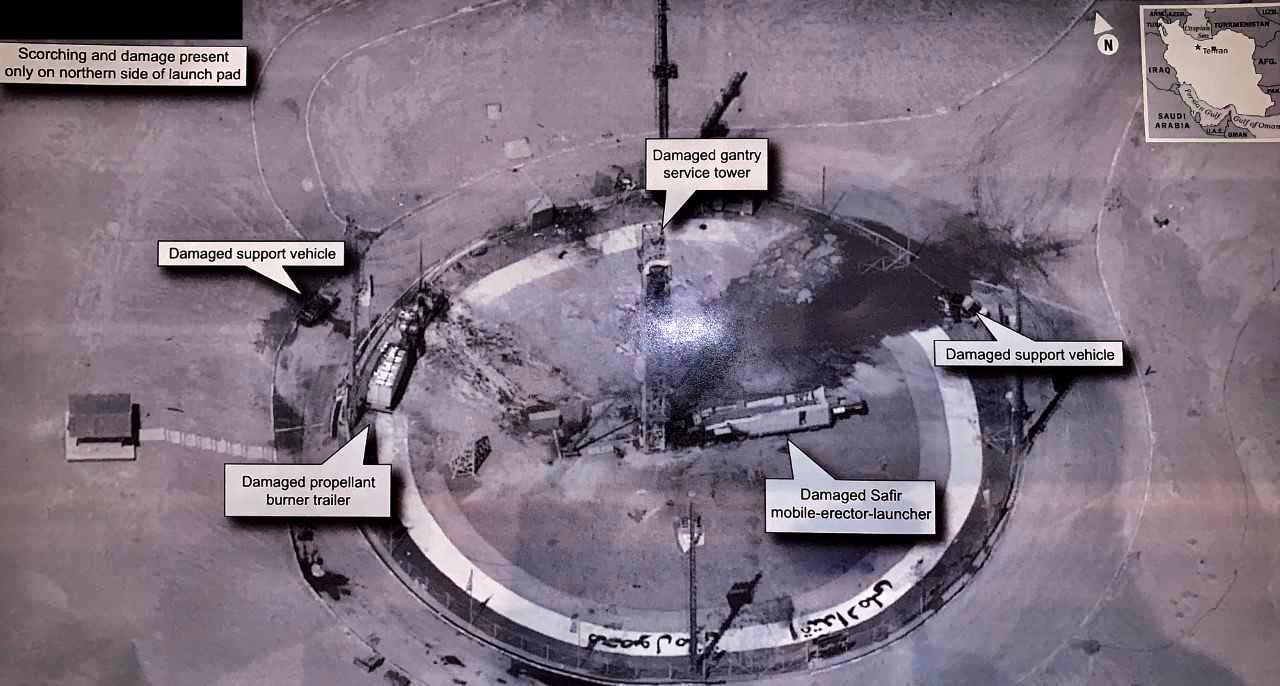

A day after commercial satellite images revealed a smoke plume over an Iranian launch pad, President Trump tweeted a remarkably high-resolution aerial photograph of the remote satellite launch facility Friday — apparently from a classified satellite or airborne drone — and denied U.S. involvement in the accident.

“The United States of America was was not involved in the catastrophic accident during final launch preparations for the Safir SLV Launch at Semnan Launch Site One in Iran,” Trump tweeted. “I wish Iran best wishes and good luck in determining what happened at Site One.”

The Safir is a two-stage Iranian satellite launcher, and the accident was the third time Iran has failed to place a satellite into orbit this year.

Trump’s attachment to the tweet of a photograph showing a detailed aerial view of the launch drove imagery analysts and satellite experts into a frenzy. The image Trump tweeted appeared to be taken from a cell phone or other type of camera, showing a digital or printed rendering of a surveillance photograph captured from an intelligence-gathering drone or satellite.

In either case, Trump’s disclosure appears to reveal new details about the U.S. government’s normally secret intelligence-gathering capabilities. U.S. presidents can declassify information at their own discretion.

The United States of America was not involved in the catastrophic accident during final launch preparations for the Safir SLV Launch at Semnan Launch Site One in Iran. I wish Iran best wishes and good luck in determining what happened at Site One. pic.twitter.com/z0iDj2L0Y3

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 30, 2019

Within hours, analysts and amateur satellite trackers joined forces on social media and Internet forums to track down a possible source of the image Trump tweeted.

Christiaan Triebert, a visual investigations journalist at the New York Times, deduced from shadows in the image that it was taken between 1:30 and 2:30 p.m. local time, probably on Thursday. Open-source orbital data compiled by amateur trackers indicated that a top secret U.S. government spy satellite flew over the Semnan launch site during that time, according to Michael Thompson, a graduate student at Purdue University studying astrodynamics and spacecraft navigation.

Using public data, Thompson calculated that the satellite, officially designated USA-224, passed over the Iranian space center shortly after 2:10 p.m. local time Thursday.

Marco Langbroek, an experienced tracker of satellite movements who lives in the Netherlands, confirmed that the USA-224 spacecraft was over the Semnan launch base around that time. In a post to the SeeSat-L Internet forum, where enthusiasts share their satellite sightings, Langbroek wrote the “angle from which the image seems to be taken … matches the post-culmination direction for USA-224.”

The USA-224 satellite is a suspected KH-11 type electro-optical surveillance satellite owned by the National Reconnaissance Office. It launched Jan. 20, 2011, aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 4-Heavy rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

KH-11 satellites are believed to carry telescopes with 7.9-foot (2.4-meter) mirrors, the same size as the primary mirror of the Hubble Space Telescope.

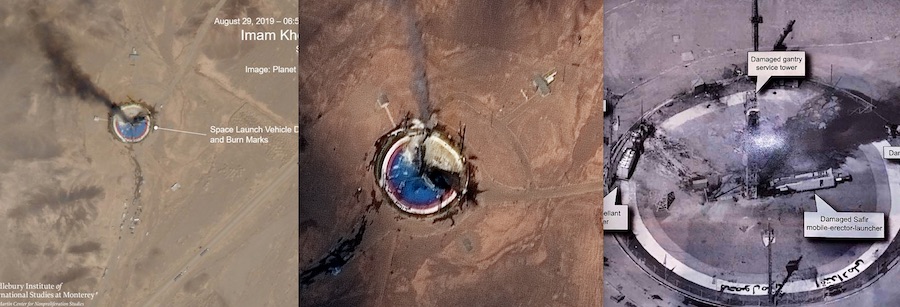

An image captured by Thursday by Planet, a U.S. company that operates a fleet of small Earth-observing satellites, showed a smoke plume coming from the circular launch pad at a space center in north-central Iran’s Semnan province.

The image acquired by Planet, first published by NPR, suggested an explosion occurred on the launch pad, perhaps minutes before the privately-owned satellite took the photo.

Reuters quoted an anonymous Iranian official who said the Safir rocket exploded “due to some technical issues” before its launch with a small satellite. Iranian officials have not disclosed any casualties from the accident.

A higher-resolution view released by Maxar Technologies showed more detail from the company’s WorldView 2 satellite.

Planet’s flock of CubeSats can resolve objects on the ground as small as 3 meters, or about 10 feet. WorldView 2’s best resolution is around 18 inches, or 46 centimeters. The photo shared by Trump on Twitter appears to be from a significantly more capable imaging instrument.

The image collected by the U.S. government is “miles” better than commercial satellite photos, said Ankit Panda, an adjunct senior fellow in the Defense Posture Project at the Federation of American Scientists. “Night and day difference.”

“You can tell someone just held up a cell phone and snapped it,” said Jeffrey Lewis, an arms control expert at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, California. “Look at the flash and arm shadow. At least someone blocked out the classification marking.”

“Trump’s tweeted image was not from any sensor we in the (open source) community can access,” tweeted Allison Puccioni, a U.S. Army veteran and former civilian senior analyst and operations planner for the Navy SEALs.

“The dissemination of this image seems out-of-step with the U.S. policy regarding its publication of such data,” tweeted Puccioni, an expert in imagery and geospatial analysis who is now affiliated with the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University. “Not sure what the political objective of dissemination was.”

U.S. government officials have released images from government spy satellites before, but in degraded form to disguise the spacecraft’s capabilities.

Despite the superior quality of the government-produced image, it was Planet’s fleet of orbiting sentinels that led to the first public knowledge that something went wrong on the Iranian launch pad.

The presence of support vehicles in the imagery suggests the accident occurred during launch preparations, perhaps during fueling of the Safir rocket, experts said.

The Iranian government said recently teams were preparing a microsatellite named Nahid for launch in the coming weeks. An Iranian official tweeted an image Saturday purporting to show him with the Nahid satellite after the launch pad explosion, suggesting it was not present during the Safir accident.

Dave Schmerler, a senior research associate at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, told Spaceflight Now that commercial satellite imagery from Planet has “revolutionized” the ability of open source analysts to study weapons activity around the world.

“I can get a picture of pretty much any place on the planet every day at 3 meters” with Planet’s satellites, Schmerler said in an interview. “So at 3 meters, I can see vehicles moving, I can see the pad changing.”

“We were watching this site for a couple of months after we noticed in June that they were clearing off the circular pad that the failure just happened at,” Schmerler said. “Some time earlier this year there was a flash flood, and it had covered the pad in mud.”

Planet has more than 100 “Dove” CubeSats in orbit to collect regular images of every place on Earth. The San Francisco-based company has also launched 15 larger “SkySat” satellites to take higher-resolution images.

Planet sells its imagery to commercial customers and the U.S. government, which uses the wide coverage offered by the Dove CubeSats to detect changes and other activity that could then be photographed by the NRO’s much bigger narrow-angle surveillance satellites.

Before Planet’s proliferation of Earth-observing satellites, it was harder for open source analysts to track activities at remote, hidden launch facilities, such as those in Iran or North Korea.

“What you’d have to do is wait for someone to say a DoD (Department of Defense) official said that something is happening at the site, and then you’d have to contact a traditional satellite imaging company, and you’d have to pay a couple thousand dollars to task a satellite to go look for a specific place,” Schmerler said in an interview with Spaceflight Now.

“That’s like throwing a dart in the dark,” he said. “You have no idea what you’re getting, but hopefully it shows some type of activity to corroborate or conflict with the reports coming out. Now that we have daily imagery, it’s kind of like sensory overload. At some point, it might even be a problem because we have so much data.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.