SpaceX is likely to land the first stage of the Falcon 9 rocket set for launch April 30 on a drone ship just off the coast of Cape Canaveral, not at the company’s onshore recovery site as originally planned, after a ground test of the company’s Crew Dragon capsule at the landing pad ended in an explosion Saturday.

Workers were examining wreckage from the Crew Dragon spacecraft at Landing Zone 1, the site where Falcon 9 boosters return to Cape Canaveral, prompting the company to apply for authority from the Federal Communications Commission to land the first stage on next week’s mission on SpaceX’s drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean.

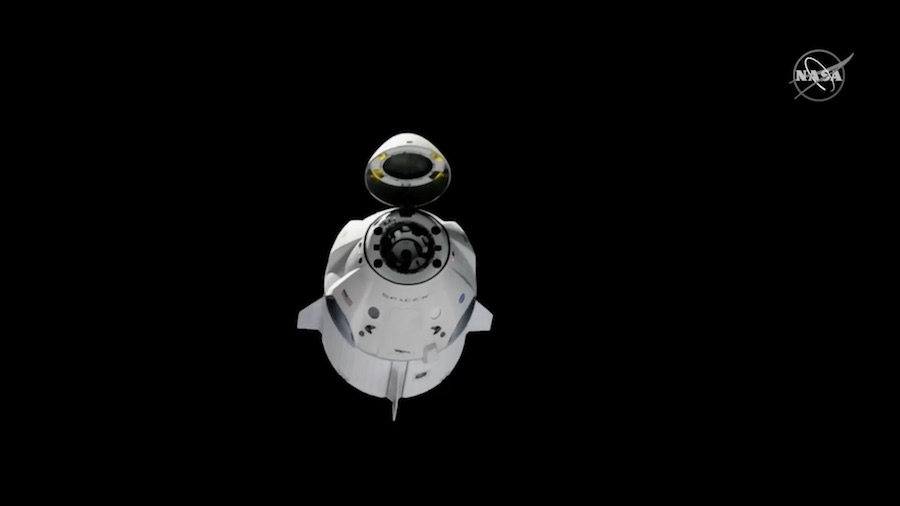

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, featuring a brand new first stage, is set for liftoff at 4:22 a.m. EDT (0822 GMT) April 30 from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad. The launcher will carry into orbit a Dragon cargo capsule packed with several tons of supplies and experiments heading for the International Space Station.

Industry officials confirmed Tuesday that SpaceX will likely attempt a drone ship landing on next week’s mission to “ensure the integrity” of the Landing Zone 1 area and “preserve valuable information” in the aftermath of Saturday’s Crew Dragon test mishap.

According a SpaceX license application dated Monday, the drone ship will be positioned roughly 17 miles (28 kilometers) southeast of pad 40, or due east of the easternmost point of Cape Canaveral. Weather permitting, the rocket’s predawn return to Earth should be visible from land.

The landing will allow SpaceX to refurbish and re-fly the booster on a future mission. Falcon 9 launches with Dragon cargo freighters carry sufficient fuel reserves for the first stage to reverse course and return to Cape Canaveral, rather than land on SpaceX’s drone ship.

A NASA spokesperson said, as of Monday, that the Dragon cargo mission remained scheduled for launch April 30. It will be SpaceX’s 17th resupply mission to the station since 2012 under a NASA contract valued at more than $3 billion.

A hold-down firing of the Falcon 9’s Merlin main engines at pad 40 is scheduled for Thursday.

SpaceX and NASA officials in the coming days are expected to review any potential impacts on the resupply mission stemming from the investigation into the Crew Dragon test accident.

The Crew Dragon spacecraft, also known as Dragon 2, is a much different spacecraft than SpaceX’s first-generation Dragon capsule.

Saturday’s accident occurred during a hotfire test of the Crew Dragon’s SuperDraco abort thrusters, according to SpaceX and NASA officials. The SuperDraco thrusters, which would be activated to save astronauts from a failing rocket, do not fly on the Dragon variant set for launch next week.

The spacecraft that exploded on the test stand Saturday was the same vehicle that completed a six-day test flight to the International Space Station last month. SpaceX was conducting ground tests on the capsule in preparation for its reuse on an in-flight abort demonstration in the next few months, a test intended to verify the SuperDraco thrusters can safely propel the spacecraft away from a Falcon 9 rocket under extreme aerodynamic pressures.

SpaceX and NASA have said little about Saturday’s accident, but the mishap is expected to delay the Crew Dragon program by months. A different test vehicle will have to be used for the in-flight abort test, which was planned to be one of the final milestones before NASA approves the spacecraft to carry astronauts to the space station.

With the Demo-1 capsule no longer available for the in-flight abort, SpaceX will have to shuffle its plans and outfit a different vehicle for the high-altitude escape test.

The unpiloted Crew Dragon test flight to the space station in early March, designated Demo-1, achieved all of its major objectives, including the first automated docking of a U.S. spacecraft to the station. But NASA officials said at the time that engineers needed to complete further testing and analysis on the Crew Dragon’s thrusters and parachutes, along with pressurant tanks on the spacecraft and the Falcon 9 rocket, before deeming the capsule ready for human occupants.

NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley are assigned to the Crew Dragon’s first piloted mission, named Demo-2.

The most recent schedule indicated the Demo-2 launch was targeted for no earlier than July 25 from pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Officials familiar with the schedule said before Saturday’s mishap that the Demo-2 mission was likely to be pushed back to late September or early October.

The Crew Dragon is one of two commercial spaceships funded by NASA to ferry astronauts to and from the space station.

SpaceX has won a series of NASA contracts totaling more than $3.1 billion since 2010 to develop the human-rated Crew Dragon spacecraft. The crew contracts are separate from SpaceX’s multibillion-dollar cargo-carrying deal with NASA.

A similar set of contracts were awarded to Boeing, worth more than $4.8 billion, to support the design and development of the CST-100 Starliner spacecraft.

The Crew Dragon is designed to launch aboard SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket from pad 39A at Kennedy, while the Starliner capsule will lift off on United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 rocket from nearby pad 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Both are designed to accommodate up to seven crew members, but will typically ferry four astronauts at a time, along with cargo.

SpaceX’s crew capsule returns to Earth with a splashdown at sea under four parachutes. Cushioned by airbags, the Starliner will land under chutes on the ground in the Western United States.

Both vehicles use liquid-fueled “pusher” escape systems to quickly boost the capsules away from a launch emergency. Other crew capsules, such as Russia’s Soyuz, NASA’s 1960s-era Apollo and future Orion spacecraft, use a “tractor” abort system relying on top-mounted towers with solid-fueled rocket motors to “pull” the vehicle away from its launch vehicle.

Once the rocket is out of the atmosphere, the abort towers are jettisoned because they are no longer needed. The Crew Dragon’s SuperDraco thrusters, which SpaceX originally designed to support propulsive pinpoint touchdowns, stay with the spacecraft from liftoff through landing.

SpaceX did away with the propulsive landing plan in 2017, electing to return the Crew Dragon capsules to Earth with more conventional ocean landings.

The Crew Dragon’s thrusters consume hypergolic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants, which chemically ignite when mixed together. The ship’s Draco thrusters are used for in-orbit maneuvers and pointing, while eight larger SuperDraco thrusters — packaged in pairs into four propulsion modules — are used for launch aborts.

Each SuperDraco engine has a 3D-printed chamber and can produce up to 16,000 pounds of thrust, with the ability to restart multiple times.

Boeing has also run into trouble during abort testing.

During a hotfire of the Starliner’s abort engines last year, stuck valves in the craft’s propulsion system led to a fuel spill on a test stand in New Mexico.

Each CST-100 service module carries four launch abort engines, built by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The engines would only fire in flight in the event of a launch emergency, igniting with 40,000 pounds of thrust each for a few seconds to propel the capsule away from its rocket.

Like the Crew Dragon’s SuperDraco engines, the Starliner abort engines burn a mixture of toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants, and are designed to almost instantly ramp up to full thrust and fire for only a few seconds. The requirement demands the abort engines to guzzle huge quantities of propellant pushed into the thrusters at high pressure.

Boeing officials said the fuel leak did not damage the test article, but the mishap forced engineers to make minor design changes to part of the Starliner’s propulsion system, including hardware and software modifications.

Earlier this month, Boeing said new valves were being installed into the Starliner’s abort engines for another hotfire test, followed by a pad abort test to prove the system’s ability to safely propel the capsule away from danger on the launch pad.

SpaceX successfully accomplished the pad abort test in May 2015 using a boilerplate version of the Crew Dragon. When the agency negotiated the commercial crew contracts, NASA did not require either company to complete an in-flight abort demonstration, and Boeing decided to forego such a test.

Boeing now plans the Starliner’s first orbital test fight, without astronauts, in mid-August, followed by the capsule’s first test flight with astronauts in November. Both demo missions will dock with the space station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.