STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

Thirteen years outbound from Earth and a billion miles past Pluto, NASA’s New Horizons probe is healthy and on course for a historic New Year’s Day flyby of its next target, a frozen remnant left over from the birth of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago, project scientists say.

Unofficially dubbed Ultima Thule (pronounced TOO-lee) in a NASA naming contest, the small 20-mile-wide body is one of countless denizens of the vast Kuiper Belt extending beyond the orbit of Pluto, taking 296 years to complete one trip around the sun. New Horizons is the first spacecraft to target a close encounter with a Kuiper Belt object, passing within 2,170 miles of Ultima Thule on Jan. 1.

“Ultima Thule comes from Latin and it means ‘beyond the farthest frontiers,’ which is exactly what we’re doing,” said Alan Stern, the New Horizon’s principal investigator. “We’re making the farthest exploration of worlds in the history of space exploration. The spacecraft is now about a billion miles farther out than Pluto, which itself was the farthest world ever explored.”

At Ultima Thule’s distance of 4 billion miles from the sun — 43 times farther than Earth — it will take radio signals carrying high-resolution pictures, spectroscopic data and other priceless information, traveling at 186,000 miles every second, six hours seven minutes and 58 seconds to cross the gulf to Earth.

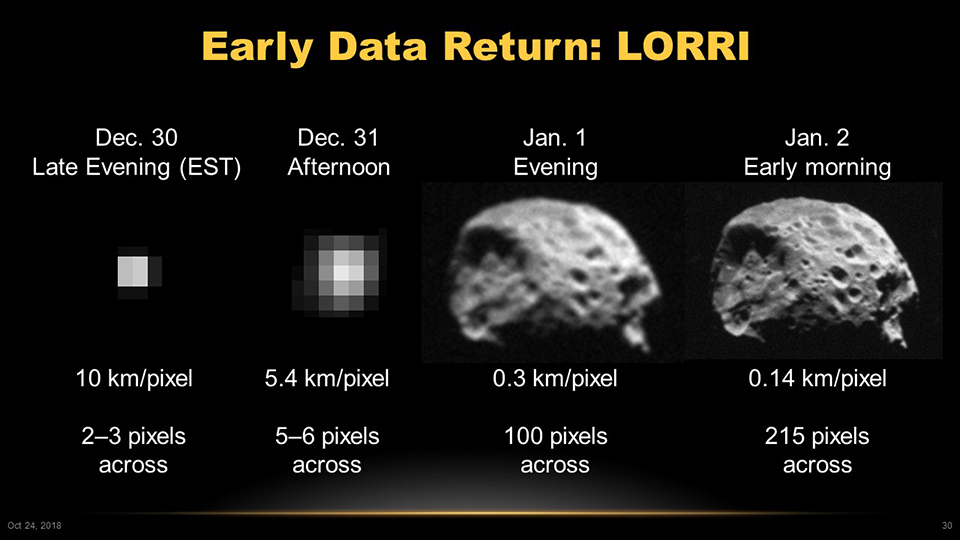

Given the enormous distance and the spacecraft’s 30-watt radio transmitter, it will take 20 months to beam back the full treasure trove of data collected before, during and after the flyby. But a sampling of high-resolution images is expected to reach scientists gathered at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory the evening of Jan. 1 and the morning of Jan. 2.

“We have no idea what to expect,” Stern told reporters Wednesday at the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Knoxville, Tenn.

“We’re going to an entirely new type of world, something formed much farther out than anything we have ever explored and which has been kept in this tremendous deep freeze of the outer solar system for the entire four billion years since its formation,” he said.

Said Carey Lisse, a New Horizons Science Team collaborator at the Applied Physics Laboratory: “If New Horizons’ (Pluto) flyby has taught us anything, expectations aren’t reality. We got totally surprised at Pluto, we’re going to get surprised again.”

“Ultima Thule could be heavily cratered, highly pitted or it could even be smooth from ancient flows and ancient activity,” he said. “We don’t know. We simply aren’t going to know until we get there in January. I’m waiting to be surprised.”

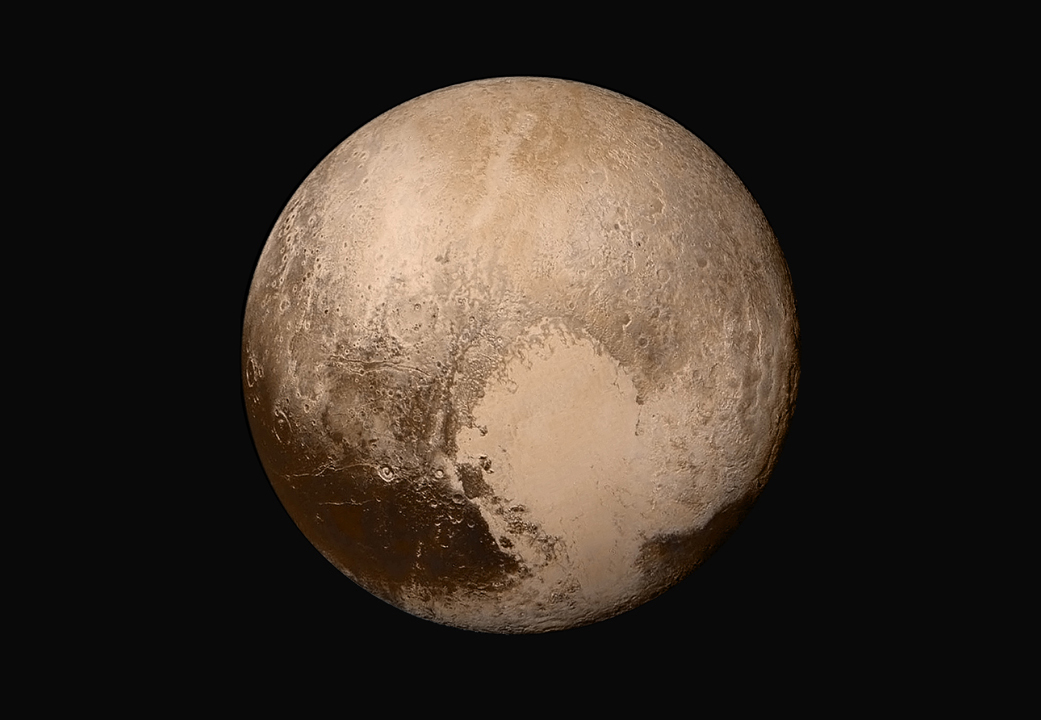

Launched in January 2006, New Horizons flew past Jupiter in February 2007, using the giant planet’s gravity to fling it onto a fast-track trajectory to Pluto. Even so, it took another eight years to reach its target in July 2015, flying past at a distance of 7,800 miles to collect the first close-up pictures of the famously demoted dwarf planet.

Even before the encounter, mission planners sought help from the Hubble Space Telescope to look for possible targets of opportunity beyond Pluto that might be close enough to New Horizons’ trajectory to permit a subsequent flyby.

Ultima Thule was discovered by Hubble in 2014 and after the Pluto encounter, NASA managers approved a mission extension and New Horizons’ course was adjusted to set up the Jan. 1 flyby.

Based on occultation observations in which Ultima Thule passed in front of a background star, scientists believe the target is either bi-lobed or elongated. New Horizons first “saw” its quarry on Aug. 16, at a distance of more than 100 million miles, but it is so much smaller than Pluto it appeared as a barely distinguishable pinpoint of light.

It will not be much more than that until New Year’s Eve.

“When we were 10 weeks out from Pluto, we could already resolve its disk about as well as the Hubble Space Telescope and each week we can see more and more detail,” Stern said. “But Ultima 10 weeks out is just a dot in the distance. And it will remain as a dot in the distance until literally the day before the flyby when we start to resolve it.

“By the day after the flyby, we’ll have high resolution images, we hope even higher resolution than the best images of Pluto. So it’s going to be quick.”

During the spacecraft’s approach, scientists will use its cameras to scan the area around Ultima Thule — the official name is 2014 MU69 — to look for any signs of dust, moonlets, rings or other possible hazards that might pose a danger to New Horizons. Flight planners can divert the spacecraft with an engine firing as late as mid December, moving the aim point farther away if required.

“There’s some danger and some suspense because we don’t know in detail what the hazard environment might be,” Stern said. “Our spacecraft is traveling at 32,000 miles an hour, that’s about 10 miles per second almost, and a collision with even the smallest shard would probably be fatal to the spacecraft. We’re conducting a hazard watch using the on-board telescopes and cameras and we’re prepared … to divert from the closest approach to a little be father out where it may be safer.”

New Horizons is equipped with a suite of sophisticated instruments: a color camera and infrared spectral imager, an ultraviolet spectral imager, a high-resolution camera and sensors to detect electrically charged solar wind particles, high-energy particles and dust. Its radio and high-gain antenna also are used for radio science investigations.

If all goes well, New Horizons will map the body’s geology, surface color and composition, search for signs of ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane and water ice, search for satellites and/or rings and look for any signs of cometary coma-like features.

Regardless of what it finds, New Horizons’ flyby of Ultima Thule “is going to be historic.”

“The New Year’s going to bring us some wonderful new knowledge from the edge of our solar system,” Stern said. “We’re going to set some new records and we are really looking forward to bringing this to the public, to engage the public in what NASA does best, which is to explore. There is one thing you can say about Ultima for sure, it’s far out.”

The same day Stern was outlining the road ahead for New Horizons, a Southwest Research Institute team he headed released a preliminary report demonstrating the feasibility of an electric-propulsion spacecraft designed to orbit Pluto, using the gravity of its large moon Charon to repeatedly change course and eventually fling it out into the Kuiper Belt.

The spacecraft would use the Charon gravity assists to visit each of Pluto’s four smaller moons for close-up observations and even to directly sample the dwarf planet’s tenuous atmosphere during low-altitude passes.

“This tour is far from optimized, yet it is capable of making five or more flybys of each of Pluto’s four small moons, while examining Pluto’s polar and equatorial regions using plane changes,” said Tiffany Finley, who designed the orbital tour. “The plan also allows for an extensive up-close encounter with Charon before dipping into Pluto’s atmosphere for sampling before the craft uses Charon one last time to escape into the Kuiper Belt for new assignments.”

Stern, a staunch supporter of the Pluto-is-a-planet school of thought, said the Southwest Research Institute study proves a single spacecraft can both explore the Pluto system in detail as well as carry out multiple observations in the Kuiper Belt.

“Who would have thought that a single mission using already available electric propulsion engines could do all this?” Stern said in a release describing the mission’s feasibility. “Now that our team has shown that the planetary science community doesn’t have to choose between a Pluto orbiter or flybys of other bodies in the Kuiper Belt, but can have both, I call this combined mission the ‘gold standard’ for future Pluto and Kuiper Belt exploration.”