A $1.8 billion U.S. Air Force communications satellite rode a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket into orbit Wednesday from Cape Canaveral, joining three similar craft perched more than 22,000 miles above Earth to ensure government leaders can remain in contact with military commanders in the worst-case scenario of nuclear war.

The Air Force relay satellite, built by Lockheed Martin with payload contributions by Northrop Grumman, will join three other Advanced Extremely High Frequency satellites to form a global network military officials say will be resilient to jamming, cyber attacks, and even nuclear war.

“This is the nation’s only strategic and tactical protected communications satellite network,” said Mike Cacheiro, Lockheed Martin’s vice president of protected communications and AEHF program manager. “It’s also the only system that survives through a near nuclear burst and can provide communications through scintillated environments that other communications systems could not.

“So, on a really bad day, you really want to have this system in place,” Cacheiro said in a conference call with reporters before Wednesday’s launch.

The AEHF 4 satellite, weighing around 13,600 pounds (6,170 kilograms), lifted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station at 12:15 a.m. EDT (0415 GMT) after an apparently flawless countdown.

Powered by a Russian-made RD-180 main engine and five Aerojet Rocketdyne-built solid rocket boosters, the Atlas 5 rapidly climbed away from Florida’s Space Coast with 2.6 million pounds of thrust, turning toward the east over the Atlantic Ocean en route to the AEHF 4 satellite’s eventual perch in geostationary orbit over the equator.

The five strap-on solid-fueled motors dropped away from the Atlas 5’s kerosene-burning core stage less than two minutes into the flight, and the launcher’s Swiss-made nose fairing jettisoned around three-and-a-half minutes after liftoff.

Soaring into the rarefied environment of space, the Atlas 5’s first stage shut down and detached in the fifth minute of the mission, leaving the rocket’s Centaur upper stage — powered by a hydrogen-fueled RL10C-1 engine — to send the AEHF 4 spacecraft into an “optimized” geostationary transfer orbit.

The previous three AEHF satellites launched on Atlas 5 rockets in 2010, 2012 and 2013, but they flew on a lighter, cheaper version of the Atlas 5 with three strap-on boosters. Air Force officials decided to launch AEHF 4, and two more follow-on satellites planned for liftoff in 2019 and 2020, on the most powerful Atlas 5 variant with five solid rocket motors.

The extra lift capability enabled by the two additional solid rocket boosters allowed the Atlas 5’s Centaur upper stage to deposit the AEHF 4 satellite closer to its final operating position in geostationary orbit.

Cacheiro said the orbit reached on Wednesday’s mission will allow the AEHF 4 satellite to more quickly arrive in its perch in geostationary orbit. Like most geostationary communications satellites, AEHF 4 will use an on-board engine to maneuver into its final orbit.

The cost of adding two boosters to the Atlas 5 rocket was outweighed by the benefits of deploying AEHF 4 in a higher orbit, Cacheiro said.

“The money’s well worth (it) in terms of the impact to the satellite and the overall program,” Cacheiro said. “It surely will provide a savings in fuel for additional life, but it’s really also a question of how quickly we get to (geostationary) orbit.”

The Centaur’s third engine firing Wednesday, timed for nearly three-and-a-half hours after liftoff, aimed to place the AEHF 4 spacecraft in an elliptical geostationary transfer orbit with an apogee, or high point, of 21,933 miles (35,299 kilometers), a perigee, or low point, of 5,539 miles (8,914 kilometers), and an inclination of 12.8 degrees.

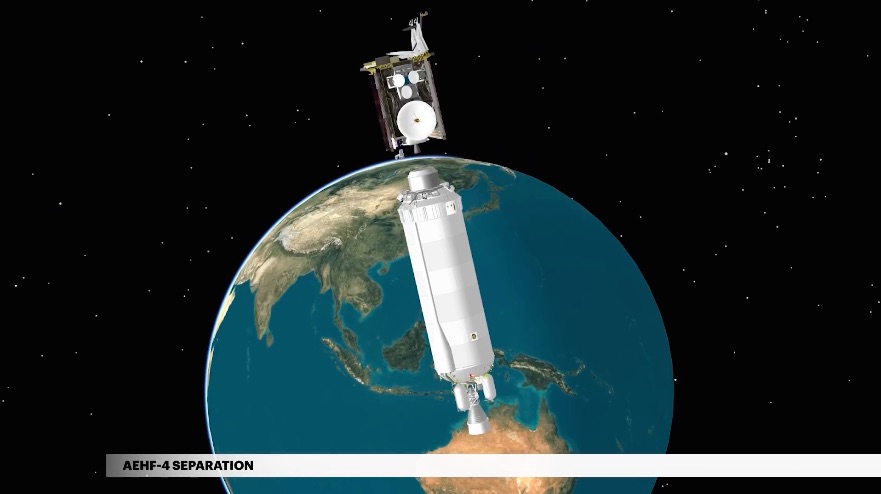

United Launch Alliance confirmed the rocket deployed the AEHF satellite into an on-target orbit at 3:47 a.m. EDT (0747 GMT), and Lockheed Martin said ground controllers immediately established a radio link with the new spacecraft.

“It’s good to return with our mission partners to see the culmination of expertise, skill and partnership that we have worked diligently toward to make this AEHF launch a success,” said Cacheiro said in a post-launch statement. “This is a substantial milestone for AEHF, and as we look ahead, we continue to improve and upgrade this mission to deliver these vital communications capabilities to the Air Force.”

The AEHF 4 satellite was expected begin raising its orbit to circularize its altitude more than 22,000 miles over the equator, where its velocity will match the rate of Earth’s rotation, giving the new craft a fixed geographic coverage zone. Other post-launch steps planned for the satellite include the extension of its power-generating solar arrays, and deployment of multiple antennas.

The AEHF fleet replaces the Air Force’s aging Milstar network, which consists of five satellites launched on Titan 4 rockets from 1994 through 2003. The new system introduces higher data rates and other improvements to the Milstar network.

“When we have the fourth AEHF satellite launched and transitioned to operations, we’ve achieved our baseline constellation of four satellites around the Earth, and that will give us the ability, if we choose, to use the extended data rate, or XDR code, which is 10 times the data rate that we currently use on the Milstar constellation,” said Col. David Ashley, AEHF program manager at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center.

The AEHF satellites are cross-linked in orbit, allowing the spacecraft to relay signals to one another without transmitting to Earth. Each satellite also carries gimbaled dish antennas to reach users on-the-move, phased array antennas with beams can be steered electronically rather than mechanically, and nulling antennas to provide “extremely high anti-jam capability to in-theater users,” according to Northrop Grumman, which developed the AEHF communications payload.

“At a time when the military is facing evolving jamming and cyber threats, protected communications capabilities are more important than ever,” Cacheiro said. “Advanced EHF is built to withstand and overcome even the toughest and most sophisticated jamming threats that are out there. For that reason, it is central to our assured resilient communciations for our warfighters and our commanders-in-chief.

“Advanced EHF is not only incredibly secure,” he continued. “It delivers unprecedented speed and bandwidth for protected communications. In fact, one Advanced EHF satellite provides ths same capacity of the existing constellation of five Milstar satellites that we have on-orbit today.

“At a time when you want to deliver videos from our warfighters, what used to take days now takes hours,” Cacheiro said. “What used to take hours for data messages now takes minutes. For voice data, what used to take minutes now takes seconds. We are truly bringing unprecedented capability to the warfighter.”

The AEHF satellites are designed for 14-year service lives.

The AEHF system’s highest data rate service, XDR+, will not be available until 2020, when the military services will have the ground terminals needed to use the full capability of the AEHF satellites, officials said.

“With this fourth satellite, it’s going to form a ring around geosynchronous orbit and allow the constellation to transition to XDR+,” Cacheiro said. “Whether it’s the president, or forward deployed troops in peace or war, our promise to the customer, the Air Force, and to the warfighter is to provide systems that become national assets.”

What differentiates the AEHF network from other military communications satellite programs is its ability to withstand threats.

“Our spacecraft has been designed to be strategically hardened … It actually is designed to keep things from coming in and radiation from penetrating,” Cacheiro said.

“One of the very unique elements of the Advanced EHF program can be equated to almost machine learning or artificial intelligence,” he said. “We have autonomous detection and recovery, so for every event that occurs, our satellite is programmed to counter that event with a specific action.

“That’s a pretty intense capability, so if there’s a near event, our satellite detects it, safes itself, and continues to support its mission,” Cacheiro said.

AEHF 4 was supposed to launch last year, but the Air Force requested Lockheed Martin modify a part on the satellite to meet a new mission requirement, according to Cacheiro, who declined to identify the new requirement publicly.

The AEHF system is a joint program between the U.S. military, Canada, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The Australian government could join the partnership soon, Ashley said

Lockheed Martin built the first three AEHF satellites in a block buy from the Air Force, but the military waited until 2013 to order the fourth AEHF spacecraft, raising the AEHF 4 satellite’s unit cost to $1.8 billion due to production inefficiencies, Cacheiro said.

“That production gap drove both some inefficiencies in our ability to produce it, as well as an increased cost,” Cacheiro said.

Two more AEHF satellites, AEHF 5 and 6, are set for launch on Atlas 5 rockets in July 2019 and March 2020, according to Ashley.

The Air Force has spent more than $10 billion on the AEHF program since its inception, including research and development, production and launch costs, according to Pentagon budget documents.

ULA’s next launch is scheduled for Nov. 29 from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, when a Delta 4-Heavy rocket — the biggest in the company’s launcher fleet — will carry a top secret U.S. government spy satellite into orbit.

Wednesday’s launch was the fifth and last Atlas 5 flight of the year. The next Atlas 5 mission is expected no earlier than March with Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner crew capsule, which will be flying on an unpiloted demo mission to the International Space Station ahead of a crewed test flight later next year.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.