A powerful commercial communications satellite driven by plasma thrusters rode a reused SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket booster away from Cape Canaveral early Monday, climbing into orbit to connect companies, homes, airplanes and ships across much of the Eastern Hemisphere.

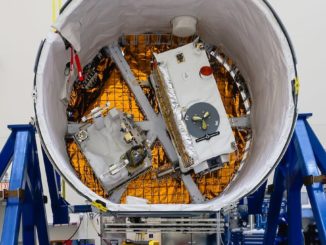

Cocooned inside the Falcon 9’s nose cone, SES 12 satellite lifted off from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad at 12:45 a.m. EDT (0445 GMT) Monday, around 16 minutes later than planned.

SpaceX previously delayed the launch from May 31 to conduct additional checks on the launcher.

The 229-foot-tall rocket pivoted its engines to steer east over the Atlantic Ocean, joining the rising waning gibbous moon in a starry sky as the rumble from its nine Merlin main engines rippled across the Florida spaceport.

The Falcon 9 dropped its previously-flown first stage into the Atlantic Ocean nearly three minutes after liftoff, and its modified Merlin upper stage engine powered up to generate more than 200,000 pounds of thrust.

SpaceX did not intend to retrieve the first stage on Monday’s mission. It was based on an earlier-generation design no longer in production.

The launcher’s payload fairing jettisoned a few moments later, and the second stage engine switched off nearly eight-and-a-half minutes into the mission, beginning a nearly 18-minute coast across the Atlantic Ocean.

The engine reignited at around T+plus 26 minutes as the Falcon 9 and SES 12 sailed over Africa, hurling the payload into an orbit arcing more than 36,000 miles, or 58,000 kilometers, above Earth tilted at an angle of 26 degrees to the equator.

SES officials confirmed ground controllers established contact with SES 12 a few minutes later, indicating the satellite was healthy following launch.

Assembled by Airbus Defense and Space in Toulouse, France, the SES 12 satellite carries plasma thrusters mounted to articulating robotic arms for nearly all its in-orbit maneuvers, eliminating the need for large conventional liquid propellant tanks.

SES 12 weighs 11,867 pounds (5,383 kilograms) with its supply of xenon propellant for the electric thrusters, while a satellite with similar capability would weigh up to 10 metric tons if it carried the customary hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants used by conventional spacecraft.

The weight savings allowed SES to fit SES 12 on a smaller, less expensive rocket, and permitted engineers to combine two communications missions into one spacecraft. SES 12 will provide direct-to-home television broadcasts, video and data relay services, and broadband connectivity across the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific, and Australia during its 15-year mission.

“This is basically two satellites in one,” said Martin Halliwell, SES’ chief technology officer. “If we built this thing years ago, we would have actually built two satellites, but we had the opportunity with Airbus together to bring them into one common bus by using the electric orbit-raising capability.”

SES 12 will use its plasma jets to climb into a circular geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator after deployment from the Falcon 9 rocket into the initial elliptical transfer orbit.

A small reservoir of conventional chemical propellant will help nudge the spacecraft out of its initial transfer orbit, but most of the orbit-raising maneuvers will use the plasma thrusters, Halliwell said.

SES 12 will slide into an operating post along the equator at 95 degrees eest longitude for its commercial telecom mission.

The Falcon 9 rocket launching SES 12 used a previously-flown “Block 4” version first stage refurbished after a September 2017 mission with the U.S. Air Force’s X-37B spaceplane.

The newly-built upper stage included upgrades introduced by SpaceX for the “Block 5” version of the Falcon 9 rocket.

“We’ve actually stripped everything off the first stage, so there are no landing legs on-board,” Halliwell said before the launch. “This is going straight into the ocean. The first stage is a Block 4 and the upper stage is a Block 5.

“We get a lot of performance from this vehicle,” he said in a pre-launch briefing with reporters.

The drawback of using low-thrust plasma jets for orbit-raising is it takes months, instead of weeks, to maneuver a communications satellite into geostationary orbit. But the high-altitude orbit targeted by the Falcon 9 rocket’s upper stage will save some of SES 12’s own fuel supply, adding years to its expected operational lifetime.

“The good side of all this is it actually extends our life capability from 15 to 22 years, so that’s enormous,” Halliwell said. “Secondly, it allows us to get into (geostationary) orbit a little bit quicker, so we’re going to save about 20 days on our orbit-raising. This allows us to come into service in late January or February of next year.”

“This is the most powerful spacecraft that we’ve ever had built for us,” Halliwell said. “The total output power is around about 16 kilowatts on the payload, 19 kilowatts overall. It’s really, really big.”

“More content. More immersive viewing experience. Blazing internet speeds. Reliable cell coverage,” Halliwell said in a post-launch statement. “All of these dynamic customer requirements can now be met with the successful launch of SES 12, which will provide incremental high performance capacity and offer greater reliability and flexibility to our customers.”

At 95 degrees east longitude, SES 12 will be co-located with the SES 8 communications satellite, which launched on a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral in 2013. SES 12 replaces telecom capacity currently provided by the aging NSS 6 launched by an Ariane 4 rocket in 2002.

The SES 12 and SES 8 satellites together will reach 18 million television homes, beaming HD and Ultra HD programming to customers in the Middle East, South Asia, the Asia-Pacific, and across Australia and neighboring islands.

The high-throughput payload aboard SES 12 will support broadband Internet and data services for remote users, airplane passengers, cruise ships and merchant vessels.

SES 12 will join a growing SES fleet, which includes satellites in geostationary orbit and 16 spacecraft and 16 O3b broadband stations orbiting at a lower altitude of around 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) over the equator.

“This is an incredibly flexible satellite that we’re putting into our fleet,” said John-Paul Hemingway, CEO of SES Networks. “By the time we get this up there, we’re going to have nearly 70 satellites in our entire constellation across both geostationary and medium Earth orbit.”

SES 12 has “wide beam coverage from the eastern parts of Europe and eastern parts of Africa all the way over to Australia, and up into the southern parts of Russia,” Hemingway said. “It really is great coverage, and of course we’ve got the very focused high-throughput beams that we can lay down wherever we need to have that capacity.”

The launch of SES 12 marks a pause in SES’ geostationary fleet expansion and replacement campaign. The company’s next geostationary satellite, SES 17, is set for launch in 2020 aboard an Ariane 5 rocket.

Four additional O3b satellites are booked to launch into medium Earth orbit in 2019 on a Russian-built Soyuz booster provided by Arianespace, and SES has purchased seven next-generation O3b mPower broadband satellites for launches starting in 2021. Launch arrangements for the O3b mPower craft have not been announced.

The next SpaceX launch is scheduled for late June from Florida with a Dragon supply ship carrying several tons of supplies to the International Space Station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.