Gearing up for a predawn blastoff July 31, launch crews have positioned a Delta 4-Heavy rocket in the starting blocks on a seaside launch complex at Cape Canaveral as engineers inside a tightly-controlled clean room a few miles away put the final touches on a NASA probe that will travel closer to the sun than any mission before.

The mission’s key components were on the move earlier this month, with the Parker Solar Probe’s shipment from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory to Florida’s Space Coast on April 3. After arriving in Florida aboard a U.S. Air Force cargo plane, the spacecraft was trucked to a clean room at the Astrotech Space Operations payload processing facility in Titusville.

Meanwhile, technicians inside the Delta 4 rocket’s assembled the launcher’s three first stage booster cores since their arrival from United Launch Alliance’s factory in Decatur, Alabama, on two shipments aboard the company’s Mariner rocket transport ship last July and August. Workers connected the Delta 4-Heavy’s upper stage in early March, then transferred the launcher to Cape Canaveral’s Complex 37B launch pad April 16.

Hydraulic lifts hoisted the rocket vertical inside the launch pad’s mobile gantry April 17, beginning checkouts that will include several launch day rehearsals, including a fueling test, in the coming months.

Liftoff is scheduled for July 31 during a two-hour launch window that opens at approximately 4:15 a.m. EDT (0815 GMT).

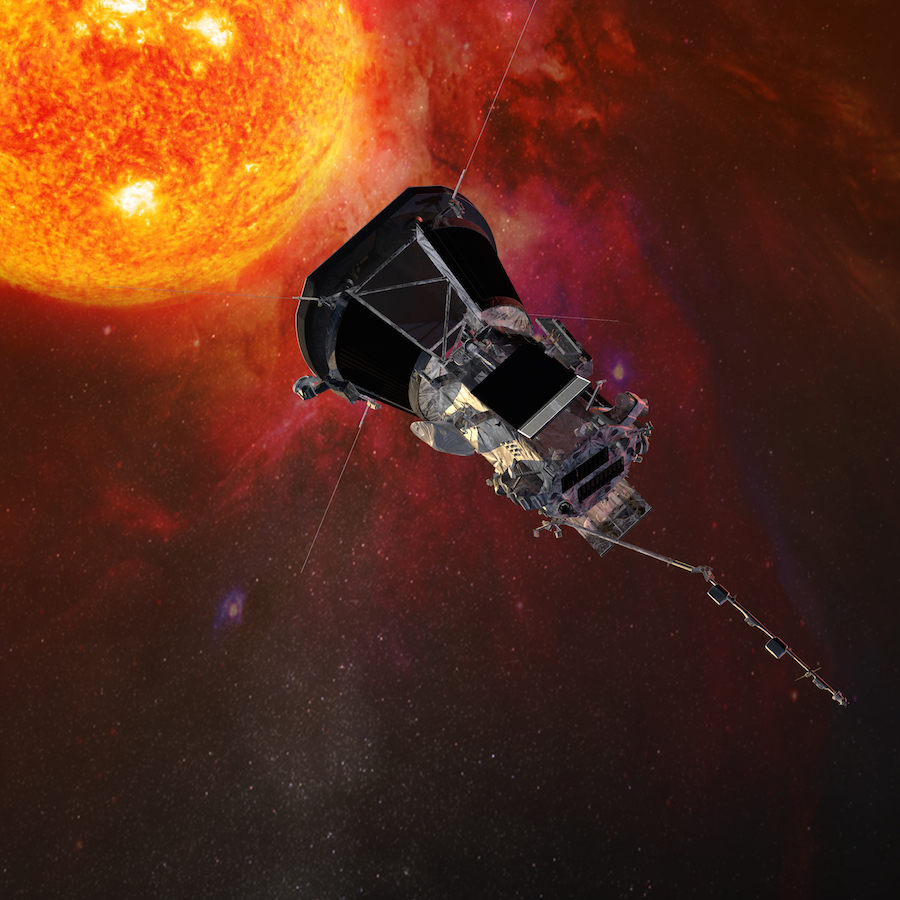

Named for Eugene Parker, the scientist who predicted in 1958 the influence of the solar wind, the Parker Solar Probe will fly closer to the sun than any past mission, reaching a point in December 2024 as close as 3.8 million miles — less than 6.2 million kilometers — from the sun’s visible surface, also known as the photosphere.

The Helios 2 spacecraft, a joint project by NASA and the German space agency, is the current record-holder. It flew 27 million miles — 43.4 million kilometers — from the sun in April 1976.

That record will be shattered early in Parker Solar Probe’s mission. With the help of a big boost from the Delta 4-Heavy rocket, the most powerful launcher currently certified to carry NASA missions into space, and an extra impulse from a solid-fueled Star 48BV upper stage provided by Orbital ATK, the 1,500-pound (685-kilogram) Parker Solar Probe will reach Venus on Sept. 28 for a flyby that will use the planet’s gravity to redirect the spacecraft’s orbit inside the orbit of Mercury.

The big rocket, upper stage and repeated encounters with Venus are required to nudge Parker Solar Probe closer to the sun, effectively slowing the spacecraft from its initial 18-mile-per-second speed — relative to the sun — at Earth’s orbit to allow solar gravity to pull it closer.

“Since we’re going so close to the sun, we have to lose a lot of energy, a lot of angular momentum, associated with the Earth’s orbit,” said Jim Kinnison, Parker Solar Probe’s mission system engineer, in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “To do that, we need a really big rocket that can provide us with a high (escape velocity). The Delta 4-Heavy was the best we could get, but even that wasn’t sufficient. We still need a third stage to provide even more of a boost for us. The third stage will do that, but we’re also targeting Venus for gravity assists to lose even more.”

SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket can carry heavier cargo than the Delta 4-Heavy, but the launcher must complete multiple successful flights before NASA will allow it to dispatch the agency’s most expensive science probes. At the time of NASA’s selection of the Delta 4-Heavy rocket for the Parker Solar Probe mission in early 2015, the Falcon Heavy was still three years from its first test flight.

Parker Solar Probe will reach its first perihelion — or close-up solar flyby — on Nov. 1 at a distance of around 15 million miles (24.1 million kilometers).

Six more flybys with Venus will crank the probe closer to the sun over the course of 24 orbits through 2025.

Parker Solar Probe will eventually fly through the corona, a super-heated envelope of plasma surrounding the sun where temperatures soar to millions of degrees. The temperature at the surface of the sun is hundreds of times cooler, but still a blistering 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (6,000 degrees Celsius).

“That just doesn’t make sense,” said Nicola Fox, Parker Solar Probe’s project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, which built the spacecraft and leads the science team. “You have a heat source, and it gets hotter as you move away. It’s like walking away from a campfire and suddenly getting hotter. It breaks the laws of nature. It breaks the laws of physics.”

Scientists believe the million-mile-per-hour solar wind, a stream of plasma that travels outward through the solar system, is generated inside the corona.

Fox said that inside the corona, plasma “gets incredibly energized, so much so that it actually takes off and can break away from the huge pull of the sun with so much energy that it can move out, and it bathes all of the planets. It carries with it the sun’s magnetic field.”

The result, Fox said, is that the Earth is impacted by solar activity, producing geomagnetic storms as the solar wind interacts with the planet’s magnetosphere, activating colorful auroral displays, potentially damaging satellites and disrupting communications and electrical grids.

“We live in the atmosphere of the sun, so when the sun sneezes, the Earth will catch a cold,” Fox said in a presentation last month at the SXSW festival in Austin, Texas. “We feel whatever is going on on the sun.”

Key questions Parker Solar Probe was designed to address include charting the flow of heat and energy that accelerates the solar wind, collecting data that could help scientists forecast solar storms that might affect Earth.

During its closest approaches in 2024 and 2025, Parker Solar Probe will experience 478 times the sunlight present at Earth, which orbits around 93 million miles (150 kilometers) from the sun. The spacecraft’s velocity will jump to roughly 430,000 mph — 120 miles per second or nearly 700,000 kilometers per hour — during its final perihelion passages.

Parker Solar Probe carries a heat shield to protect the spacecraft’s most critical parts from the scorching temperatures, but the craft’s power-generating solar panels and some parts of its scientific payload will remain exposed.

“We will be orbiting through the 3-million-degree plasma region,” Fox said. “That sounds really hot, but the plasma there is not very dense. If you imagine turning your oven on to 400 degrees and letting it heat up, you could put your hand inside that oven. It won’t burn you unless you touch something, so there’s a difference between temperature and heat.

“There aren’t that many particles around, so the actual amount that couples into the front side of our heat shield means that the front side is about 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1,400 degrees Centigrade (Celsius),” Fox said.

Behind the heat shield, or thermal protection system, the main body of the spacecraft will be warmed a little hotter than room temperature, but still within engineering tolerances for crucial parts like the probe’s computer and propulsion system.

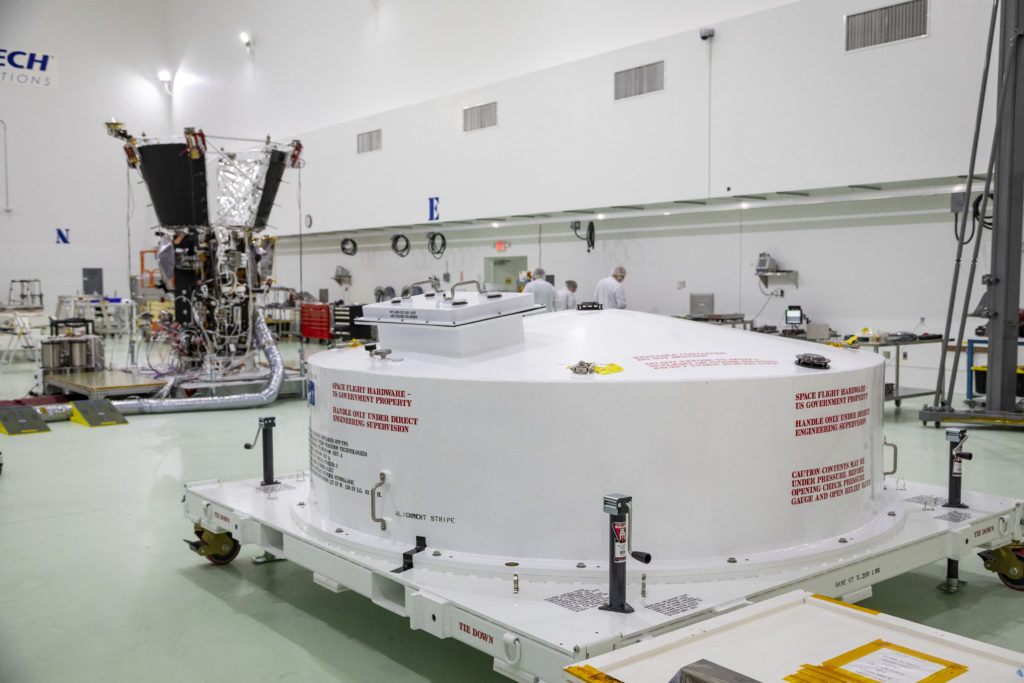

Parker Solar Probe’s heat shield arrived at the Astrotech facility in Titusville, Florida, on April 18 in a ground shipment from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL, in Laurel, Maryland.

One of the major activities at Astrotech in the lead-up to launch will be the installation of the heat shield, a 4.5-inch thick (11.4-centimeter) piece of carbon composite that stretches around 8 feet (nearly 2.5 meters) wide.

“The idea of exploring this region around the sun has been around for about 60 years,” Kinnison said. “The primary thing that’s kept us from doing that is the heat shield technology that will allow you to survive there … That was one of the more critical technologies that we had to develop.”

Once the heat shield is bolted on to the spacecraft, engineers will transfer Parker Solar Probe to a hazardous fueling facility where it will be loaded with hydrazine propellant. Then ground crews will connect the probe to its Star 48 upper stage motor and encapsulate it inside the Delta 4’s payload fairing before moving the spacecraft to the launch pad.

Officials are still working to resolve a couple of technical issues before clearing Parker Solar Probe for launch.

Peg Luce, the acting director of NASA’s heliophysics division at NASA Headquarters, said earlier this month that engineers are studying the failure of several platinum resistance thermometers on the spacecraft.

“The platinum resistance thermometers are lightweight, highly sensitive temperature sensors used to help provide feedback to the spacecraft’s cooling system and solar arrays,” said Dwayne Brown, a NASA spokesperson. “We put all spacecraft through a rigorous test program to make sure all systems are working as designed and it is normal for a test program to uncover issues.”

Luce said the thermometers, which contain fine wiring, could be repaired or replaced during pre-launch processing in Florida, if necessary. After assessing the situation during recent review of Parker Solar Probe’s status, officials unanimously approved the spacecraft’s shipment from Maryland to Florida, Brown said.

“There are a number of tests that we’re doing back at the lab to understand what’s going on,” Kinnison said. “These sorts of things happen with spacecraft where you come up with an issue at the end of the day, and the team pulls together and figures out what needs to be done, and we get it done. That’s what I’m expecting to happen here.”

In a presentation to a heliophysics advisory committee April 5, Luce said the mission managers are also examining “some late breaking problems that are being worked and watched very carefully” regarding the Star 48 upper stage motor.

“It all looks like that will be smoothed out in time for launch,” Luce said.

But she said NASA will not go forward with the launch if there are any lingering concerns.

“We are not going to fly this mission if we have concerns about it, and if we have to take more time, we will,” Luce said.

Parker Solar Probe’s launch period extends through Aug. 19, and is limited by the position of Venus in its orbit around the sun. If the mission misses its launch opportunity this year, the next chance to send Parker Solar Probe into space will come in May 2019.

More photos of the Delta 4-Heavy rocket’s arrival at its launch pad are posted below.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.