European engineers who developed a small satellite hitching a ride to the International Space Station aboard a SpaceX supply ship Monday are gearing up for a first-of-a-kind experiment to examine ways to snare a chunk of space junk and tug it back to Earth.

Developed in a public-private partnership, the RemoveDebris mission will test the utility of nets and harpoons to capture tumbling objects in orbit, repurposing devices commonly used in fishing to pluck debris out of orbit and bring them into Earth’s atmosphere to burn up.

Guglielmo Aglietti, principal investigator for the RemoveDebris mission, calls the project a “proof-of-concept.”

They crux of the mission, Aglietti said in an interview, is to prove that cleaning up space junk can be relatively inexpensive — something that could be affordable by commercial companies, or governments operating under budget limitations.

“We want to learn as much as possible,” said Aglietti, who is also director of the Surrey Space Center, a research institute affiliated with the University of Surrey and Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd., a British manufacturer of small satellites. “Even if some experiment doesn’t go exactly as planned, provided we get all the data, it’s still a positive outcome.”

The RemoveDebris satellite will launch in a container inside a SpaceX Dragon cargo craft set for launch at 4:30 p.m. EDT (2030 GMT) Monday from Cape Canaveral. The commercial supply ship is carrying more than 5,800 pounds (2.6 metric tons) of food, provisions and experiments to the space station’s six-person crew.

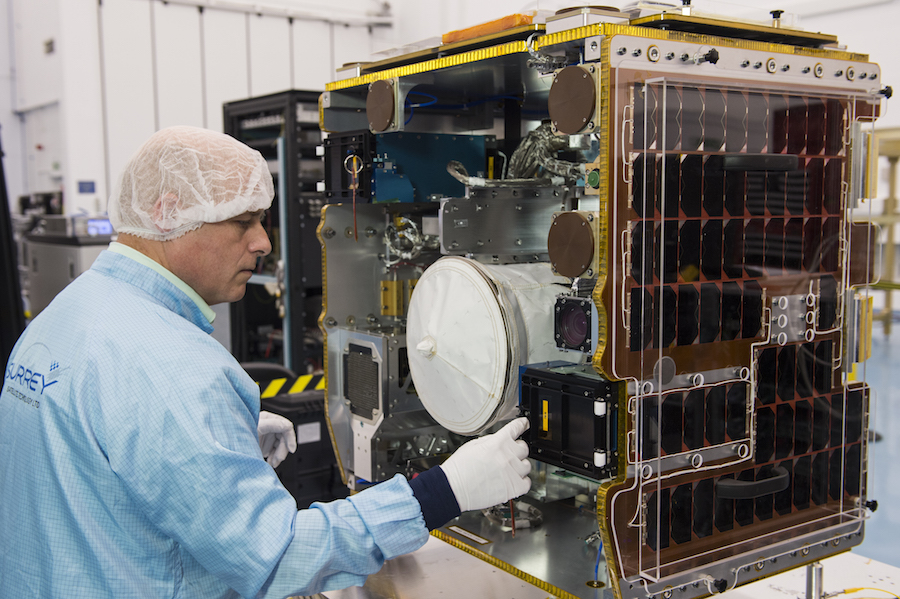

RemoveDebris accounts around 220 pounds, or 100 kilograms, of the Dragon’s cargo load.

But the small spacecraft, developed by SSTL in the United Kingdom, punches above its weight. The RemoveDebris mothership contains two CubeSats, a net and a harpoon, a laser ranging instrument, and a “dragsail” designed to unfurl behind the main satellite and hasten its fall back into Earth’s atmosphere using aerodynamic resistance.

Assuming the Dragon resupply mission takes off Monday, the cargo capsule is due to reach the space station early Wednesday. Astronauts will unpack the RemoveDebris satellite, along with tons of other equipment, in the following weeks.

Some time this spring, the crew will take the one-meter cube-shaped spacecraft from its shipping container, remove shields used to protect it during launch, then place it on a sliding tray inside the Japanese Kibo lab module airlock.

Fixed to a NanoRacks carrier, the spacecraft will transfer through the airlock to the Japanese lab’s outside science deck, where the Kibo module’s robotic arm will grab it and move to a predetermined position for release.

Aglietti said RemoveDebris is currently slated for deployment from the space station in late May, but the schedule is not yet confirmed.

“The mission will really start once we are deployed out of the space station, hopefully at the end of May or the beginning of June,” he said.

RemoveDebris will be the biggest satellite launched from the space station. That has placed the mission under extra scrutiny from NASA managers, who want to ensure the satellite poses no hazard to the orbiting outpost or its crew.

The launch of RemoveDebris was supposed to happen last year, but officials bumped it to a later SpaceX cargo flight.

“It took a little bit longer to make sure that all the right boxes were ticked,” Aglietti said.

The demo craft’s high-flying experiments will not begin until the satellite is well away from the space station, Aglietti said. In fact, the satellite will remain in a dormant mode for around a half-hour after its release, before switching on to begin checkout procedures.

Ground controllers at SSTL’s campus in Guildford, England, will put the spacecraft through four primary experiments.

“Basically, it has a net, a harpoon and a dragsail on-board,” said Jason Forshaw, the RemoveDebris mission’s project manager at SSTL. “The concept is it’s going to go up there, and it’s going to eject small little satellites that will be used as artificial space junk.”

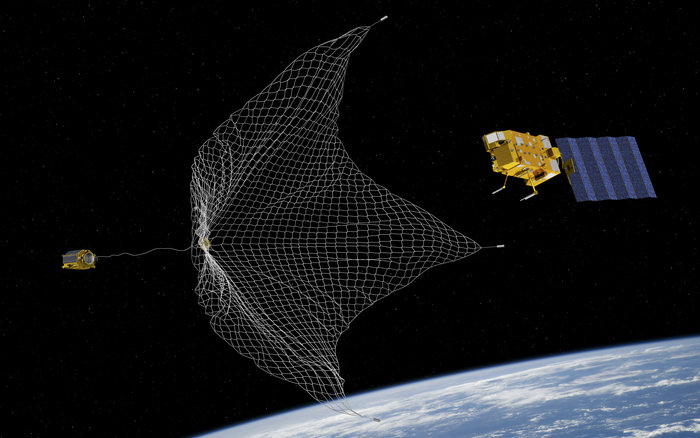

One of the CubeSats, about the size of a loaf of bread, will inflate a balloon to mimic the dimensions of a bigger piece of tumbling space junk. Flying a short distance away, RemoveDebris will release a net to envelop the CubeSat — named DebrisSat 1 — which will be cut loose to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere.

“The net, as a way to capture debris, is a very flexible option because even if the debris is spinning, or has got an irregular shape, to capture it with a net is relatively low-risk compared to … going with a robotic arm, because if the debris is spinning very fast, and you try to capture it with a robotic arm, then clearly there is a problem,” Aglietti said. “In addition, if you are to capture the debris with a robotic arm or a gripper, you need somewhere you can grab hold of your piece of debris without breaking off just a chunk of it.”

Another CubeSat, named DebrisSat 2, will separate from the RemoveDebris mothership to test out tracking and ranging lasers and algorithms. The RemoveDebris satellite will use DebrisSat 2 to test out close-up navigation technology needed for an orbiting garbage collector to approach an out-of-control piece of space junk.

The LIDAR instrument “can observe debris, and figure out all the parameters of what this debris is doing in order to plan your capture,” Aglietti said. “We have a normal camera, and then a LIDAR, which uses lasers to illuminate the object and figure out what the object is doing, and try to quantify the parameters, not just looking and seeing it, but also trying to see the spin rate, for example.”

The third RemoveDebris experiment will test the functionality of a harpoon, which would be used to fire at a dead satellite and spear it, allowing the junk to be maneuvered out of orbit for a fiery re-entry.

But RemoveDebris will not test the harpoon on an actual satellite. The technology is still untried in space, and there are legal concerns about using it to lasso someone else’s spacecraft without permission.

“Maybe it’s a bit more risky because you have to hit your debris in a place that is suitable to be captured by the harpoon,” Aglietti said. “Clearly, you have to avoid any fuel tanks … That would produce some undesired effects.”

Instead, RemoveDebris will extend an arm with a target for the harpoon on the end, then fire the projectile on a tether.

“We have harpoons, we have nets,” Forshaw said in a TEDx talk last year. “These all seem like simple concepts, and they are. They’ve been used for thousands of years underwater to capture things such as sea creatures. However, taking technologies that are mature on Earth, in the oceans, and actually bringing them up there into space and seeing (if) these concepts work for the first time — nobody has ever used a net or a harpoon for these purposes in space before.”

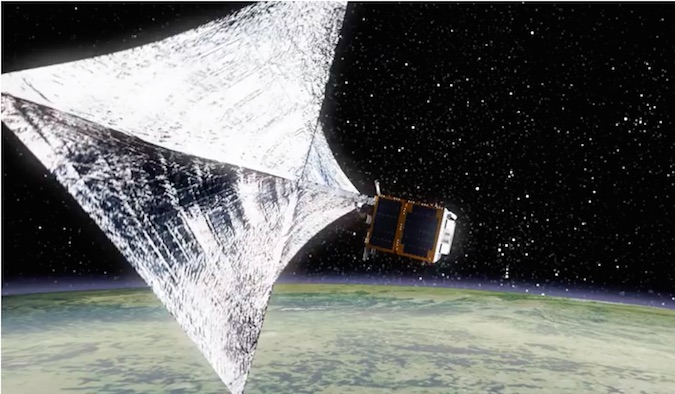

Finally, RemoveDebris will open up an expandable sail to act like an airbrake or spoiler, generating drag from collisions with air molecules in the rarefied outer atmosphere. At the space station’s altitude of around 250 miles (400 kilometers), the dragsail will bring the RemoveDebris satellite back into the denser layers of the atmosphere, where it will burn up.

“All the elements of the mission should be de-orbited very quickly,” Aglietti said. “Clearly, for a mission like ours, we don’t to further contribute to the problem of space debris. We want to make sure that all the pieces we are putting up there are going to come down pretty quickly. For us, a launch from the International Space Station is particularly good because it’s in such a low orbit, that in any case, even if some of the experiments do not work out as planned, it doesn’t matter because everything is going to come down and burn up in the atmosphere.”

Budgeted at 15.2 million euros — $18.7 million at today’s currency exchange rates — the RemoveDebris mission was partially funded by the European Commission. The rest of the project was paid by the 10 companies involved in the demonstration, including SSTL, Airbus Defense and Space, and Ariane Group.

“Since the beginning of the space era, orbital debris has progressively been building up and there are now almost 7,000 tons of it around the Earth,” said Martin Sweeting, SSTL’s executive chairman. “It is now time for the international space community to begin to mitigate, limit and control space junk, and I am very pleased that the RemoveDebris consortium is leading the way with an innovative ADR (Active Debris Removal) mission which I hope will be a precursor to future operational ADR missions.”

In-space collisions have happened before.

In 2009, a commercial Iridium communications satellite collided with a deactivated Russian military craft, destroying both objects and creating thousands more pieces of space junk.

“Satellites that get old also have residual fuels on them,” Forshaw said. “Sometimes these fuels mix, so satellites are remarkably good at exploding by themselves.”

“One of the core questions is who is responsible for all of this,” Forshaw said. “Who is responsible for keeping space tidy? There, space law is complicated. Every single item in space, whether it be a full satellite or a piece of glass, is actually owned by somebody. You can’t take away their property without their permission. Besides, if a tiny little fragment hit your satellite, you wouldn’t even know who did it.”

As companies like OneWeb, SpaceX and others build out planned “mega-constellations” of hundreds and thousands of communications satellites, the space debris problem will remain top of mind for many in the industry.

OneWeb and SpaceX say they will steer their planned broadband communications satellites back into Earth’s atmosphere once their missions are complete, but some of the spacecraft could become stranded if they suffer unexpected failures.

“There are really two solutions: Either we ensure things launched into space have the ability to come back down themselves, and/or we launch missions up there to actually capture some of this space junk and bring it back down to Earth, where it will burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere,” Forshaw said.

“Once the whole campaign is finished, and the (RemoveDebris) satellite is de-orbited, it would be great if companies offered this as a service, and there will be bigger missions when they will go and capture a real piece of debris using some of the technologies we have demonstrated,” Aglietti said.

One company established to remove space debris out of orbit is Astroscale, headquartered in Singapore. Astroscale is developing a commercial space debris capture experiment in partnership with SSTL.

The European Space Agency also has a mission concept called e.Deorbit, which would launch in 2024 to rendezvous with Envisat, a defunct Earth observation satellite that failed suddenly in 2012. Envisat is the size of a double-decker bus, and experts anticipate it will remain in space for up to 150 years, posing a hazard to other satellites in the same region of space nearly 500 miles (800 kilometers) above Earth.

The e.Deorbit mission, if approved by ESA member states, would bring Envisat down in a controlled manner. The RemoveDebris mission will check to see if some of the fundamental parts of such an endeavor will work.

“At the end of the day, everything boils down to funding,” Aglietti said. “We all agree, in the space sector, that it is a good idea to start to remove larger pieces of debris, which are the ones that cause the major threat. The problem is just financial.

“That was why we’re testing cost-effective technologies,” he said. “In my opinion, the stumbling block is the cost … If the cost to do it is exorbitant, then people will prefer to take the risk that their new satellite is going to be hit by a piece of debris. If we manage to lower the cost of the missions, then this is much more likely to happen.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.