China’s Long March 3B rocket, used to power navigation and communications satellites into high-altitude orbits, launched for the first time in nearly five months Sunday with two spacecraft for the country’s Beidou positioning network.

Sunday’s launch, declared a success by Chinese officials, marked the first flight of a Long March 3B since June 19, when a roll control error on the rocket’s third stage led to the deployment of the Chinasat 9A television broadcast satellite into a lower-than-planned orbit.

The Chinasat 9A satellite later boosted itself into its originally-intended orbit, but at the expense of fuel, reducing its expected useful lifetime.

The June 19 failure was the third in a string of four Chinese launch accidents in a span of less than a year. Chinese space officials suspended all launches in early July after a heavy-lift Long March 5 rocket failed to enter orbit.

China’s Long March 2-series rockets returned to service last month with two successful missions, while the larger Long March 3B remained grounded until Sunday.

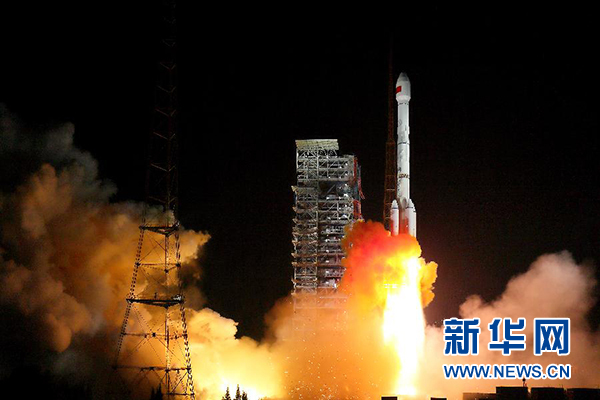

Powered by four liquid-fueled strap-on boosters and a hydrazine-burning core stage, the Long March 3B lifted off at 1145 GMT (6:45 a.m. EST) Sunday from the Xichang space center in southwestern China’s Sichuan province. The launcher apparently performed as designed.

After heading southwest from Xichang, the rocket’s hydrogen-fueled third stage was expected to deploy a Yuanzheng space tug in an elliptical, oval-shaped orbit less than a half-hour after liftoff. The Yuanzheng upper stage was programmed to maneuver the two third-generation Beidou satellites in a circular 55-degree inclination orbit about 13,700 miles (22,000 kilometers) above Earth.

U.S. military tracking data on the satellites were not immediately available Sunday, but the government agency responsible for China’s Beidou navigation system confirmed the flight was a success. Launch announcements from Chinese government sources are typically reliable.

Sunday’s launch followed the deployment of two third-generation Beidou test satellites into a so-called medium Earth orbit in July 2015.

The completed Beidou constellation will consist of 27 satellites in medium Earth orbits, five in geostationary-type orbits around 22,300 miles (36,800 kilometers) over the equator, and three in inclined geosynchronous orbits that oscillate north and south of the equator.

The satellites launched Sunday are the 24th and 25th to join the Beidou fleet, which currently includes around 15 operational navigation craft, according to a roster kept by Russia’s Information and Analysis Center for Positioning, Navigation and Timing that tracks the status of U.S., Russian and Chinese navigation networks.

When complete, the Beidou system will join the U.S. Air Force’s Global Positioning System, Russia’s Glonass satellite network, and Europe’s Galileo fleet — which is still being deployed — as the world’s four navigation services with global reach.

Named for the Chinese word for the Big Dipper constellation, the Beidou constellation achieved an initial operating capability with coverage over the Asia-Pacific region in 2012. Development of the Beidou program began in 1994.

The third-generation satellites now being launched by China feature higher-performance rubidium and hydrogen atomic clocks, inter-satellite links, improved spatial signal accuracy, better compatibility with other countries’ navigation satellites, and offer search-and-rescue services, according to a Chinese government release published on the Beidou program’s official website.

The Beidou satellites are designed to be interoperable with U.S., Russian and European navigation networks, and U.S. and international chipset producers offer receivers capable of using L-band signals from all four types of satellites. Combining signals from more satellites give users a more precise position estimate.

The third-generation Beidou spacecraft can provide positioning accuracies between 2.5 and 5 meters (8.2 to 16.4 feet), according to Chinese program officials.

China said it plans to launch 18 more Beidou satellites by the end of 2018, and the network will have more than 30 satellites by 2020, enough to begin independent global service.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.