EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated at 9:30 a.m. EDT (1330 GMT) with ULA statement.

First hotfire of our BE-4 engine is a success #GradatimFerociter pic.twitter.com/xuotdzfDjF

— Blue Origin (@blueorigin) October 19, 2017

Blue Origin has conducted the first hotfire test of its BE-4 rocket engine in West Texas, a powerplant fueled by liquified natural gas and liquid oxygen that will power the company’s heavy-lift New Glenn rocket and perhaps United Launch Alliance’s next-generation Vulcan launcher, officials announced Thursday.

The company released a six-second video of the test-firing, showing the engine from four angles. A Blue Origin spokesperson did not respond to questions on the hotfire test, and officials did not disclose the duration of the test or the engine’s throttle setting.

Backed by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, Blue Origin has developed the BE-4 engine with mostly private funding for multiple uses.

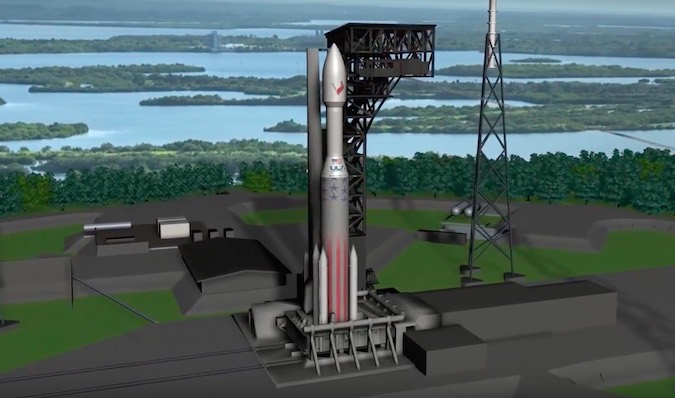

Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket, set for an inaugural launch around 2020, will have seven BE-4 engines on its first stage, and a single BE-4 engine on its second stage. United Launch Alliance has tapped the BE-4 as the primary engine option for the Vulcan rocket, a replacement for the company’s Atlas 5 rocket scheduled to debut around the end of 2019.

The reusable BE-4 can produce 550,000 pounds of thrust at sea level, making it the highest-power methane-fueled rocket engine ever built. SpaceX is working on its own high-performance methane-burning engine, called the Raptor, which company chief Elon Musk said last month will generate around 380,000 pounds of sea level thrust.

The BE-4 hotfire test is a significant milestone in the engine’s development after Blue Origin started developing the powerplant in 2011. Blue Origin originally intended the BE-4 to produce about 400,000 pounds of thrust for its own commercial New Glenn launcher, but ULA partnered in the engine’s development in 2014, and engineers scaled it up to produce nearly 40 percent more thrust.

“Congratulations to the entire Blue Origin team on the successful hotfire of a full-scale BE-4 engine,” ULA said in a statement. “This is a tremendous accomplishment in the development of a new engine.”

Jointly owned by aerospace contractors Boeing and Lockheed Martin, ULA has partially funded the BE-4’s development with private capital, but most of the engine’s funding has come from steady investments by Bezos — the second-richest American, according to a ranking by Forbes.

The U.S. Air Force has also committed at least $46 million to help integrate the BE-4 engine on ULA’s Vulcan rocket, which the military aims to use for launches of national security satellites.

“For our new rocket, the Vulcan, the majority of its investment is private, and the majority of that is actually in our own supply chain, which, by definition, is private,” said Tory Bruno, ULA’s president and chief executive.

Bruno said in April his team would confirm the BE-4’s selection for the Vulcan rocket once the engine completed an initial series of hotfire tests. He said ULA’s engineers wanted to examine the engine’s performance before a final decision on the Vulcan’s propulsion system.

“Whenever you develop a new liquid rocket engine, if you change the fuel, or if you stay with the same fuel and change the scale of the engine, or if you keep the scale, keep the fuel but change the thermodynamic cycle … Any one of those three variables can create a situation we call combustion instability,” Bruno said.

All three variables are new with the BE-4, which uses oxygen-rich staged combustion technology, a technique that minimizes propellant waste during launch. U.S. rockets are currently powered by solid-fueled boosters or liquid-fueled engines burning RP-1 kerosene or liquid hydrogen, not liquified natural gas, or methane.

Engineers contend the methane fuel used on the BE-4 makes it easier to reuse than kerosene-fueled engines like SpaceX’s Merlin powerplant, leaving less soot and other contaminants that might need to be cleaned out between flights.

Blue Origin intends to land the New Glenn rocket’s first stage on an ocean-going barge, similar to the recovery technique pioneered by SpaceX. ULA’s Vulcan rocket will initially fly as an expendable rocket, but the company is working on plans to recover first stage engines — not the entire booster — with a parafoil and helicopter for refurbishment and reuse.

The BE-4 engine suffered a setback in May, when Blue Origin announced it lost a set of BE-4 powerpack hardware during a ground test mishap. The company said such problems were not unusual in engine development, without disclosing further details.

Blue Origin announced in April that the first BE-4 engine was installed on its test stand at Bezos’s ranch near Van Horn, Texas, adding that the first hotfire test was expected “very soon.”

The BE-4 engine’s development has been based at Blue Origin’s headquarters in Kent, Washington. Once in full production, the engines will be assembled at a new facility in Huntsville, Alabama.

ULA has not announced a timetable for a final decision on the Vulcan rocket’s first stage engine. Aerojet Rocketdyne is working on an alternative engine, called the AR1, which burns kerosene and liquid oxygen.

ULA says the BE-4 engine is about two years ahead of the AR1 in development, and a Vulcan rocket with Blue Origin-built engines would be ready to fly before the AR1. But Aerojet Rocketdyne has maintained that the AR1 is the less risky option.

The Vulcan’s first stage will be powered by two BE-4s or two AR1s, ending ULA’s reliance on Russian-built RD-180 engines, which currently power the company’s Atlas 5 workhorse. ULA plans next year to retire most of its Delta 4 rocket family, which uses U.S.-built engines but is more expensive than the Atlas 5. The Delta 4-Heavy rocket, featuring three first stage booster cores, will continue flying to ensure the U.S. military’s heaviest satellites have a ride to orbit.

Once the Vulcan rocket is operational, the Atlas 5 will be retired some time in the early-to-mid 2020s.

Bruno said last month that ULA aims to complete the Vulcan rocket’s critical design review by the end of this year, then begin offering the new rocket in the commercial launch market.

The review, known by the acronym CDR, is a major step in finalizing a rocket’s design and readying it for final testing and production. ULA must settle on an engine for the Vulcan rocket before completing the review, Bruno said in remarks at last month’s World Satellite Business Week event in Paris.

“You cannot really conduct or complete a CDR — you might be able to start, but you can’t finish — until you have baselined your engine, so those are tied together,” Bruno said. “Engine development for both our providers is going well. It is event-driven … When we reach that technical maturity, we’ll be able to select. I hope to do that soon, and then that allows us to go ahead and complete the critical design review.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.