Firing off a launch pad on the fringes of the Amazon rainforest, a European Vega rocket climbed into space Tuesday night and deployed a new optical surveillance craft for the Italian military and a French-Israeli environmental satellite to monitor vegetation, snow cover and coastal waterways.

The Optsat 3000 and Venµs satellites lifted off at 0158:33 GMT Wednesday (9:58:33 p.m. EDT; 10:58:33 p.m. French Guiana time Tuesday) on the 10th flight of a Vega rocket, a four-stage booster primarily developed and manufactured in Italy.

The two satellites, both built by Israel Aerospace Industries, were paired together to share the Vega rocket launch by Arianespace, the French company charged with managing commercial missions from the Guiana Space Center, a remote outpost on the northeastern shore of South America.

Roaring into the late night sky with nearly 700,000 pounds of thrust, the 98-foot-tall (30-meter) Vega launcher turned north from French Guiana and soared over the Atlantic Ocean, Bermuda and Canada as its three solid-fueled rocket motors fired in quick succession in the first seven minutes of the mission.

A fourth stage engine burning liquid hydrazine fuel ignited four times, first to place the Optsat 3000 satellite into a planned 280-mile-high (450-kilometer) polar orbit tilted 97 degrees to the equator. The 811-pound (368-kilogram) spacecraft, destined for use by the Italian military, separated from the Vega rocket’s upper stage around 43 minutes after liftoff.

The second pair of upper stage engine firings aimed to maneuver the rocket into a higher 447-mile-high (720-kilometer) orbit with an inclination of 98 degrees for the deployment of Venµs, a scientific research satellite jointly developed by the French and Israeli space agencies.

Launch controllers announced the Venµs satellite released from the Vega rocket more than an hour-and-a-half into the mission, and Arianespace said both payloads were placed into accurate orbits.

“Arianespce is delighted to confirm that Optsat 3000 and Venµs have been safely separated in their targeted sun-synchronous orbits,” said Stephane Israel, chairman and CEO of Arianespace. “For the second time this year, and the 10th since its debut, success is here for Vega and its customers.”

Optsat 3000 and Venµs were expected to fly over an Israeli ground station around five hours after the launch, giving engineers an opportunity to verify both satellites are healthy following their trip into space. The first images from each satellite should be downlinked to the ground within a week or so, officials said.

In work since 2005, the Venµs mission is a 50-50 collaboration between Israel and France.

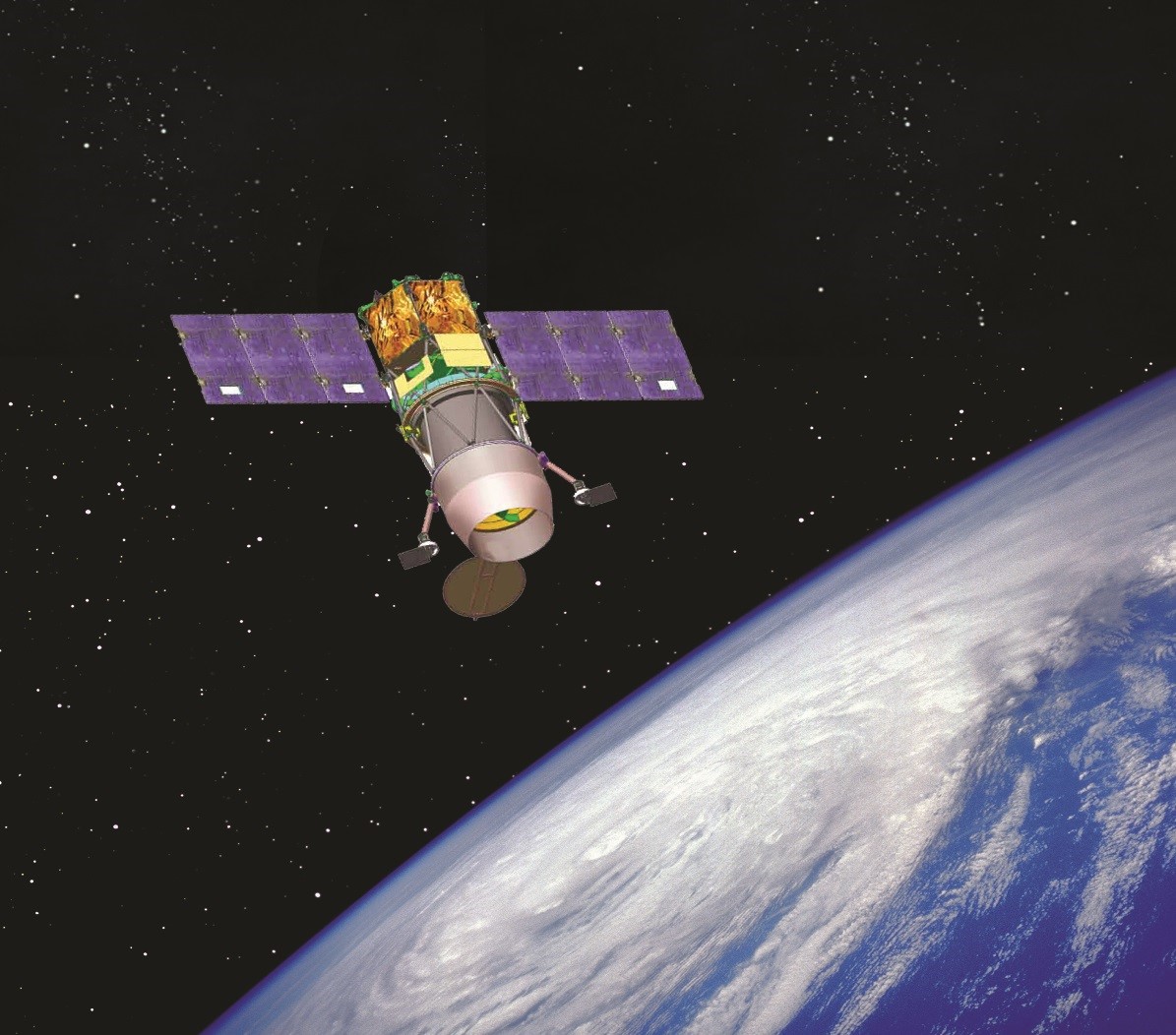

The 582-pound (264-kilogram) spacecraft carries a French-supplied “super-spectral” color camera sensitive in 12 bands ranging from blue to near-infrared. Venµs will take pictures of vegetation, glaciers, coastlines and other features from its high orbital perch.

“Venµs … will play a major role in the fight against climate change,” said Jean-Yves Le Gall, president of CNES, the French space agency.

Offering a twist on a line often repeated by French President Emmanuel Macron, Le Gall said: “Venµs will help make our planet great again.”

Scientists will point Venµs’s camera toward 110 areas of interest in forests, croplands and nature reserves around the world, according to CNES. No other satellite currently in orbit can survey the same locations with the resolution and frequency of the Venµs mission, a benefit gained at the expense of global coverage, officials said.

The United States has 24 percent of the Venµs mission’s targets, more than any other nation.

Researchers will track plant growth, snow cover, glacial movements, and sediments in coastal estuaries with the Venµs satellite. Scientists will analyze the mission’s data output to study how environmental and human factors influence vegetation health.

“Venµs will be used to model the influence of human activities or environmental factors, global warming, on the surface reflectances,” said Pierric Ferrier, Venµs project manager at CNES. “The idea is to be able to build models to study the evolution and prevent the effect of global warming and allow sustainable development.”

“The hydric stress of vegetation can be observed in some of the spectral bands of Venµs, then you will be able to monitor exactly the need of water for your plants, and in the infrared domain also you can monitor the presence of water in the soil or not,” he said.

“Each type of plant has its own spectral signature. We are able to segregate and isolate some of the crops we want to observe, and we can combine some spectral bands and get the spectral signature of each crop.”

Officials from the Israel Space Agency and CNES said each nation contributed approximately $40 million to the Venµs mission. Adding price of the launch, the mission’s total cost exceeds $100 million.

“What is really unique in Venµs is the convergence of three things,” Ferrier said. “The good resolution of 5 meters (16 feet), the spectral richness of the camera in 12 bands, and the third is revisit — two days.”

“Existing Earth observation satellites observe pre-defined zones of interest every 10 to 15 days,” Ferrier told Spaceflight Now in a phone interview. “At this frequency, you cannot observe quickly for phenomena such as plant growth, variation of snow cover, and various types of phenomena which need constant, frequent observation. So Venµs will be able to distinguish between two images taken at two-day intervals, and see what has evolved quickly between the two images.”

A software algorithm developed for the Venµs mission will help scientists remove clouds and aerosols from the satellite’s imagery, revealing minute changes on the surface.

Besides the satellite’s primary camera, France is in charge of the mission’s science data center and other ground systems. Israeli engineers built the satellite, the camera’s telescope and a experimental plasma thruster to be tested in the second phase of the Venµs mission.

IAI built a nanosatellite that launched in February that is making experimental weather observations, but Opher Doron, head of IAI’s space division, said Venµs is “the first serious research satellite Israel has done.”

“It’s a very nicely run program between the two space agences, and we hope for many more,” Doron said in an interview with Spaceflight Now.

After a two-and-a-half-year Earth observation campaign, Venµs’s altitude will be lowered to approximately 250 miles (410 kilometers) to test the low-power electric thruster’s ability to counteract the effect of atmospheric drag and maintain the satellite’s orbit.

Developed by Rafael, an Israeli defense contractor, the Hall effect thruster design could be used on future Israeli-built reconnaissance satellites.

“It’s a very exciting new capability that we plan to migrate on to other satellites to give us longer life and lower altitudes,” Doron said. “This is designed to give us a flight-proven capability.”

Venµs’s launch was delayed several years, and Ferrier said the schedule slips were primarily caused by problems obtaining filters for the satellite’s camera from Materion Barr, a Massachusetts-based company. The filters were restricted under the U.S. government’s ITAR arms control laws until the hardware was finally delivered for Venµs, delaying the launch approximately 18 months, Ferrier said.

Problems arranging the satellite’s launch triggered another delay, he said, until mission managers could find another spacecraft heading to a similar polar orbit that would be ready for liftoff at the same time as Venµs.

The co-passenger ended up being Optsat 3000, another Israeli-made satellite.

Optsat 3000 is Italy’s first optical surveillance satellite, joining a fleet of Italian radar imaging craft already in orbit. The $182 million satellite, designed for a lifetime of at least seven years, carries a Jupiter remote sensing camera provided by Israel-based Elbit Systems Ltd. capable of resolving objects on the ground smaller than a half-meter (20 inches).

“Today, we set the pace for better cooperation in defense,” said Gen. Enzo Vecciarelli, Chief of Staff of the Italian Air Force. “That’s something we really need right now.”

The Italian Ministry of Defense ordered the Optsat 3000 satellite from Israel Aerospace Industries as part of a reciprocal contract arrangement, in exchange for the Israeli military’s purchase of Italian-made jet trainers.

Telespazio acts as prime contractor for the Optsat 3000 program, and OHB Italy reserved the satellite’s launch on a Vega rocket with Arianespace.

“Optsat is our very high-end electro-optical satellite,” Doron said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “It’s going to be flying at 450 kilometers. It’s got superb resolution at that altitude.”

Optsat 3000’s imaging strength, enabled in part by its relatively low-altitude orbit, apparently bests the resolution offered by spy satellites owned by other European governments, and matches the world’s best commercial Earth observation spacecraft.

“I think it’s probably one of the more advanced satellites around,” Doron said.

Without disclosing the exact resolution of Optsat 3000’s images, Doron said it will offer “WorldView-class” image sharpness from its operating orbit. DigitalGlobe’s newest WorldView satellites have cameras capable to resolving features as small as 31 centimeters, or 12 inches, on the ground.

“The generic Optsats offer 50 centimeters (resolution) from 600 kilometers, although this one will be better because it’s lower, so it’s super-high resolution,” Doron said. “This satellite is also optimized to cover very large areas. It’s very agile, so it can cover lots of targets in many areas using different scanning modes and different scanning directions.”

Doron described Optsat 3000 as a “tool designed for practical intelligence users.”

Arianespace’s next launch is set for Sept. 1, when a heavy-lift Ariane 5 rocket will send two commercial communications satellites to orbit for Intelsat and Japan’s Broadcasting Satellite System Corp., or B-SAT.

The next flight by a Vega rocket is scheduled for no earlier than Nov. 7 with a military reconnaissance satellite for the government of Morocco.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.