A rover NASA plans to launch to Mars in 2020 will likely explore one of three locations selected last week by a scientific advisory group, which picked candidate landing sites that were once homes to ancient lakes and hot springs.

“We’re looking for a site that’s ancient — around 4 or so billion years old — because that’s when we think Mars had water flowing and a more clement environment,” said Jack Mustard, a professor at Brown University who sits on the Mars landing site selection board. “We need to be able to characterize the habitability of that environment and look for preserved biosignatures. And in addition to the science on the ground, we need to find the right samples to return later.”

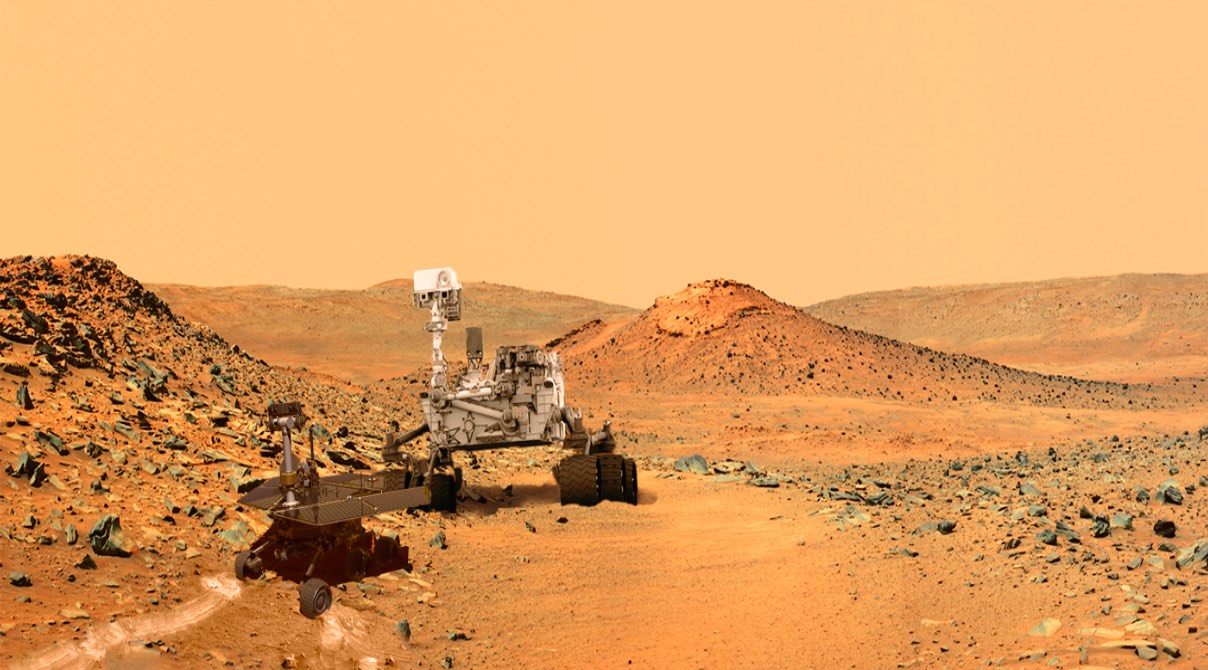

The six-wheeled robot, similar in appearance and capability to NASA’s Curiosity rover currently on Mars, will look for signs of past Martian life, assess the habitability of the environment, and measure the chemical, mineral and organic make-up of rocks, with an emphasis on hunting for biosignatures, the natural relics left behind by alien microbes.

Its other chief objectives will be to collect at least 30 test tube-sized core samples for possible retrieval and return to Earth on a future mission, and test a new device to generate oxygen from carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere, validating a tool future missions could employ to produce breathable air, water and rocket fuel.

Scientists met last week in California to narrow a list of eight potential destinations selected in 2015. Acting on the advice of the 172 researchers, NASA settled on three finalists Saturday, setting the stage for a final decision by top agency managers in 2018 or 2019.

The robotic mission, officially named Mars 2020 for now, will launch in July 2020 aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket and reach the red planet in February 2021, descending through the atmosphere with the assistance of a heat shield, parachutes and braking rockets before cables unreel to place the rover on the surface.

The “sky crane” descent system is based on the technology demonstrated with the landing of Curiosity on Mars in August 2012.

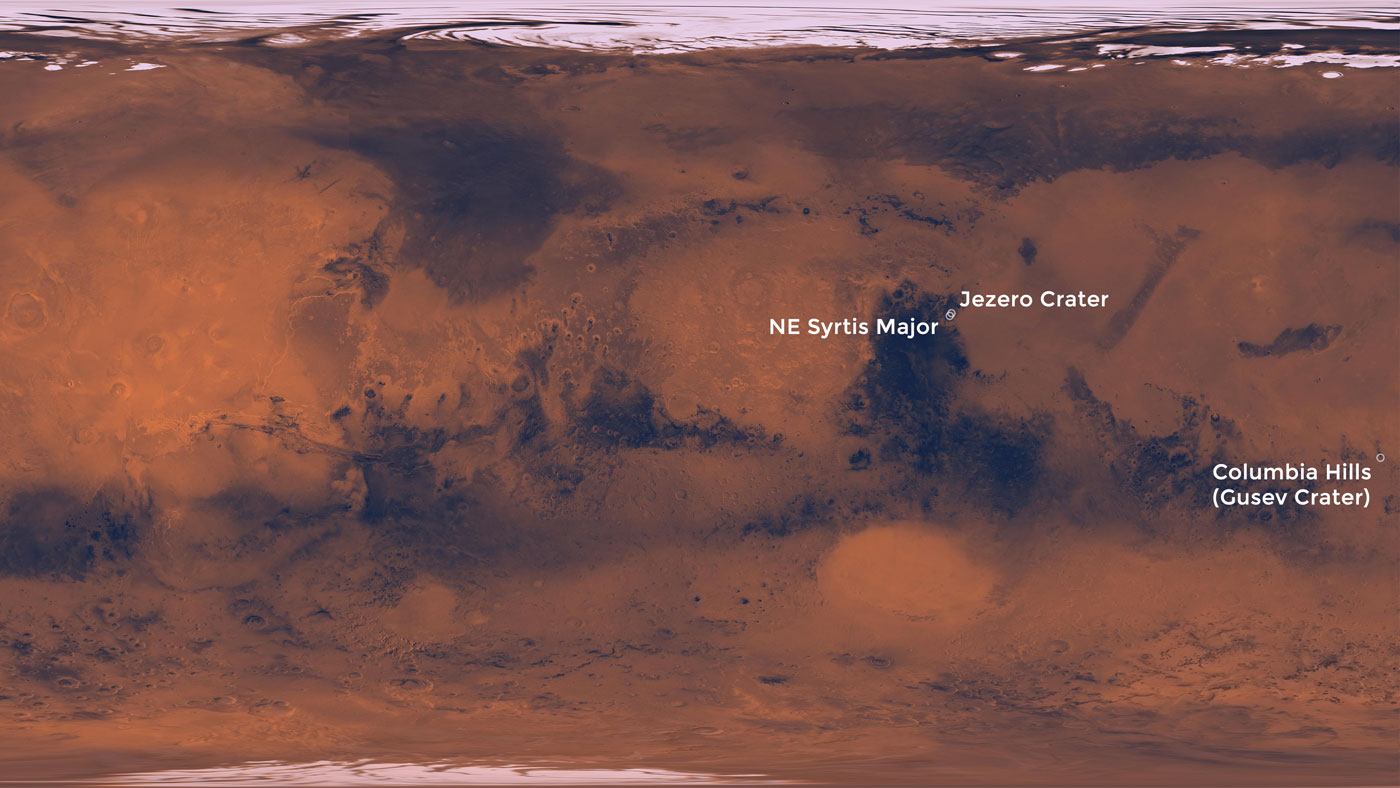

The shortlist of landing sites includes the Columbia Hills, a range of heights in 4-billion-year-old Gusev Crater where NASA’s Spirit rover landed in January 2004.

Spirit found evidence that the region had a watery past after climbing from its touchdown point in the basin of Gusev Crater into rounded highlands named for the astronauts who died aboard the shuttle Columbia.

The rover drove 4.8 miles (7.7 kilometers) during its mission, and kept going after one of its wheels stopped turning. The inoperable right-front wheel dragged up white soil — the rover’s spectrometer determined the material was nearly pure silica — and scientists linked the unexpected discovery with the presence of ancient hot springs and steam vents.

Such an environment could have hosted microbes billions of years ago, making it an ideal location to land the Mars 2020 rover, scientists said.

Spirit reached a feature named “Home Plate,” the remnant of a hydrovolcanic explosion involving three key ingredients for life: heat, energy and water. The Spirit rover, which functioned 25 times longer than its 90-day design life, also found outcrops of carbonate in the Columbia Hills, deposits which scientists say were emplaced during a wetter period of Martian history.

Data gathered by Spirit also indicate Gusev Crater could have periodically flooded and made shallow lakes.

Proponents of the Columbia Hills site also tout the possibility of sending the Mars 2020 rover to inspect Spirit where it bogged down in a sand pit in 2009 and likely froze its internal electronics during a frigid Martian winter. NASA last heard from Spirit in March 2010 and gave up on recovering the mission in May 2011.

Information on Spirit’s condition could give engineers insight into how extreme temperature swings, dust storms and possible micrometeorites affect hardware like coatings, optics, actuators and cabling on Mars, providing a bonus opportunity for a “long duration exposure experiment,” scientists said.

“This data will aid in design of future surface systems, equipment and structures for both manned and robotic exploration of Mars,” scientists wrote in a presentation backing the Columbia Hills site.

Spirit ended its mission before reaching several more geologic features scientists wanted to visit.

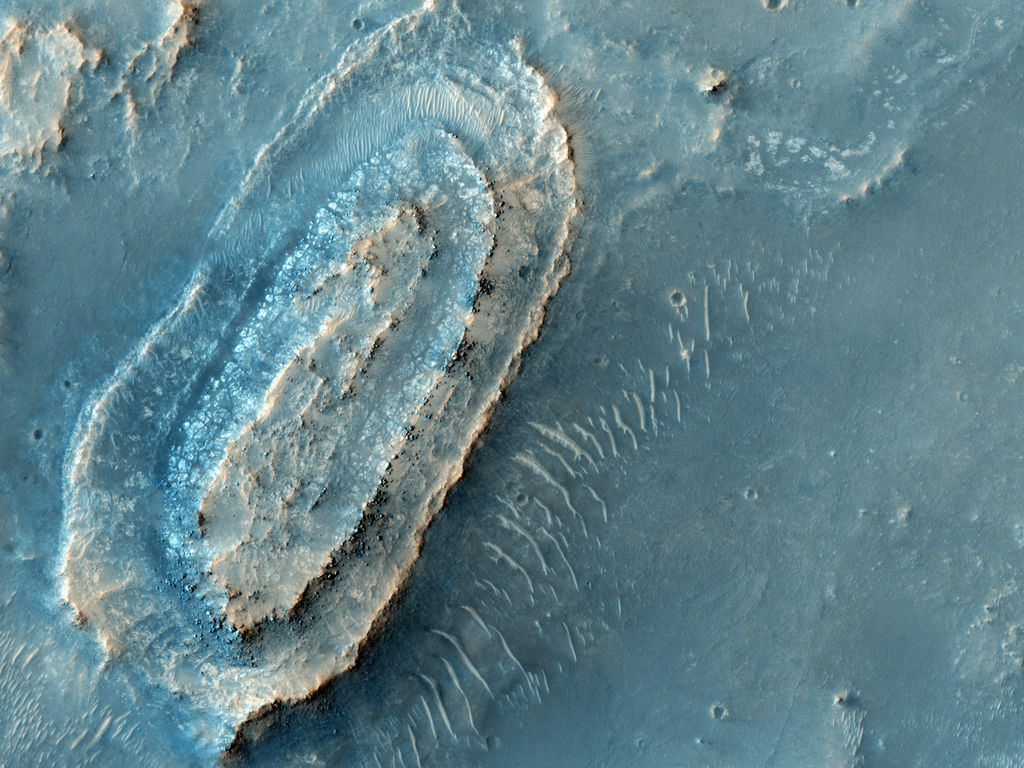

The other two potential targets for the Mars 2020 rover are Jezero Crater, home to an ancient river delta, and a region named Northeast Syrtis, a location that appears to be rich in layered clays with some of the oldest terrain found on Mars.

Jezero and Northeast Syrtis — about 30 miles (50 kilometers) apart — lie at about 18 degrees north latitude. Neither place has been explored on the surface.

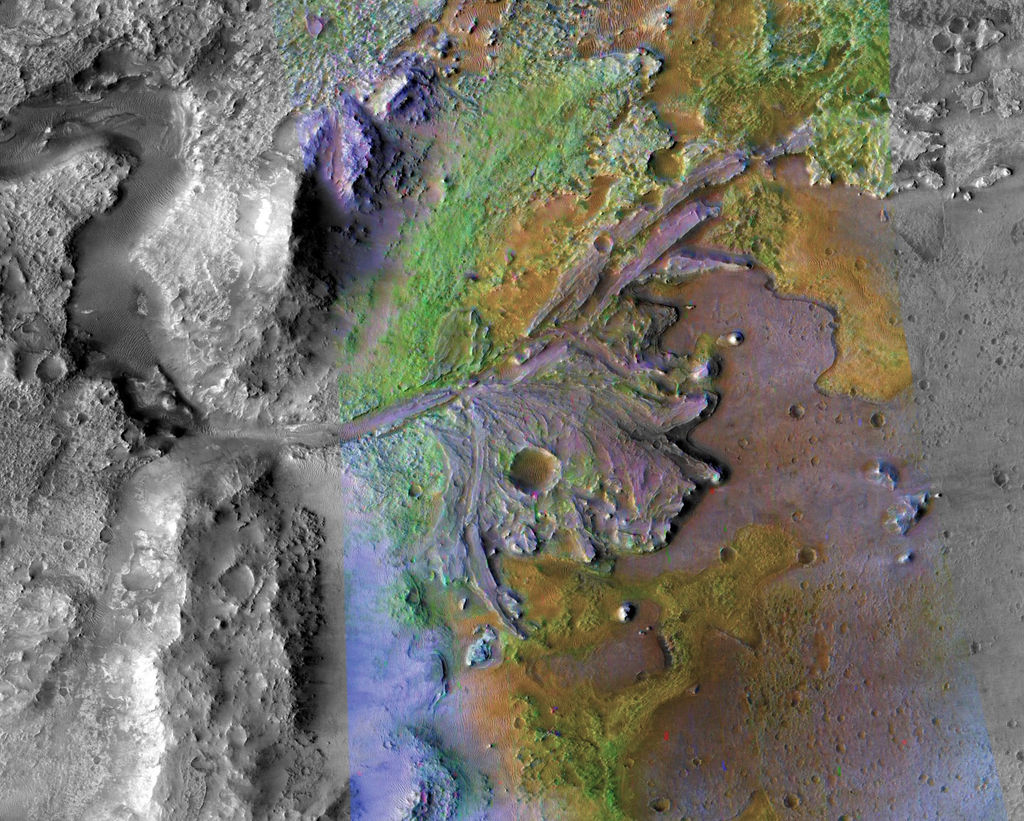

“Jezero Crater tells a story of the on-again, off-again nature of the wet past of Mars,” NASA wrote in a description accompanying the landing site announcement. “Water filled and drained away from the crater on at least two occasions. More than 3.5 billion years ago, river channels spilled over the crater wall and created a lake.”

Imagery obtained from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show clear evidence of a dried-up river delta that fed a lake. Scientists think the delta deposits, which came from a watershed stretching 4,600 square miles (nearly 12,000 square kilometers), offer one of the best places on Mars to look for preserved organic matter and biomarkers in samples the rover could scoop up and store for return to Earth by a later mission.

“Any organic matter that might have been in that [watershed] is going to get concentrated in an area we can explore with a rover,” said Tim Goudge, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin who made the case for Jezero Crater.

“That makes it easier to maybe find the needle in the haystack because you’re potentially collecting lots of needles in one spot,” Goudge said in a Brown University press release.

Once the Jezero lake dried up, water may have continued to flow into the crater, stacking layers of clay minerals that hardened to form sedimentary rock.

“Conceivably, microbial life could have lived in Jezero during one or more of these wet times,” officials wrote in Saturday’s announcement following the science meeting. “If so, signs of their remains might be found in lakebed sediments.”

Jezero received the most votes during the landing site conclave.

Orbital observations show the nearby Northeast Syrtis site, the second-leading vote-getter, is covered in the remains of an underground hydrothermal system. Supporters of this landing destination point to scattered patches of carbonate, made from interactions between water and the mineral olivine, a process that produces hydrogen molecules, a possible energy source for microbes.

“On Earth, we have evidence of these ancient lineages of bacteria that lived off of rocks in the subsurface, feeding off of chemical energy,” Mustard said in Brown’s press release. “Here we have that feedstock and there was water, so that makes it really exciting.”

The age of some of the exposed rocks at Northeast Syrtis also makes for an attractive target.

“The rocks we would touch down on would be 4 billion years old, older than any rocks on Earth,” said Mike Bramble, a Brown graduate student who also presented at last week’s landing site meeting. “So that’s a chance to answer all kinds of questions about the formation of Mars and the formation of planetary surfaces in general.”

All three candidate landing sites meet NASA’s engineering requirements, providing a safe, relatively flat and boulder-less location for the rover to touch down on the surface.

Scientific concerns will drive mission managers’ recommendation of one or two primary landing sites at a future meeting. Officials at NASA Headquarters charged with a final decision are expected to endorse one of the top destinations scientists recommend.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.