Launching from the edge of the Amazon jungle in South America, a Russian-built Soyuz booster fired into orbit Friday night with a Spanish-owned communications satellite built in Germany to test new commercial telecom technologies and provide video, voice and data relay services.

The three-stage Soyuz-2.1b rocket, topped with a hydrazine-fueled Fregat space tug, lifted off at 0103:34 GMT Saturday (8:03:34 p.m. EST; 10:03:34 p.m. French Guiana time Friday night) with Hispasat 36W-1, a satellite developed in a public-private partnership between the European Space Agency and European industry.

Darting through mostly cloudy skies, the Soyuz headed east from the launch pad at the French-run Guiana Space Center, dropping its four kerosene-fueled boosters in the Atlantic Ocean, shedding the two halves of its nose shroud and its core stage, then releasing a Fregat upper stage to guide the Hispasat 36W-1 satellite into geostationary transfer orbit.

The Fregat main engine fired for nearly 18 minutes before shutting down and deploying the 7,100-pound (3,220-kilogram) payload 32 minutes after liftoff.

Managed by the French launch provider Arianespace, the mission sent Hispasat 36W-1 into an arcing geostationary transfer orbit with a high point 22,227 miles (35,771 kilometers) above Earth, roughly the altitude of the geostationary satellite belt over the equator, the spacecraft’s final destination.

“Arianespace is delighted to announce that Hispasat 36W-1 has been separated as planned in the targeted standard geostationary transfer orbit,” said Stephane Israel, Arianespace’s chairman and CEO. “For our first launch of the year, and the 16th Soyuz since its introduction at the European spaceport, our medium-weight vehicle performed flawlessly. Congratulations to all.”

Built by OHB System AG of Bremen, Germany and owned by Madrid-based Hispasat, the spacecraft will use its own main engine to raise the low point of its orbit, currently at an altitude of 155 miles (250 kilometers), up to geostationary altitude in the coming week.

Five “orbit-raising” maneuvers are planned, then the satellite’s power-generating solar arrays and antennas will be unfurled. Once engineers complete testing the new-generation satellite platform, and its communications instrumentation, Hispasat plans to declare the spacecraft ready for operational service by early April.

Friday night’s mission was the 1,868th launch of the venerable Soyuz rocket family, based on the Cold War-era R-7 ballistic missile, and just the 16th time the launcher has flown from a pad outside former Soviet territory.

It was also the first Soyuz launch since a Soyuz rocket flying in a different configuration crashed minutes after liftoff Dec. 1, destroying a Progress cargo craft bound for the International Space Station. That launch failure, which Russian officials have blamed on foreign object debris or poor workmanship, was traced to an older-generation third stage engine not used on the Soyuz-2.1b version launched Friday.

Russian ground teams are based in French Guiana to prepare Soyuz rockets and Fregat upper stages for flight, accentuating the international nature of Friday night’s mission, which was lauded by European Space Agency director-general Jan Woerner, who called it an example of “global cooperation beyond Earthly crises.”

“We know it was a Russian launcher,” Woerner said in remarks after the launch. “Just as I was sitting there, I got a message from Igor Komarov, the head of Roscosmos, the Russian space agency. He said, ‘Congratulations on the successful launch of Hispasat. Thank our teams.’ This is what he wrote to me, and I think this shows that we can cooperate even in very difficult political situations. Space can do it, and we should always look to that. We need this bridge for the whole globe, not only for two or three countries.”

The Hispasat 36W-1 satellite, the product of a $250 million public-private partnership, will operate from a location in geostationary orbit at 36 degrees west longitude over the Atlantic Ocean, reaching Hispasat’s clients in Spain, Portugal, the Canary Islands and South America during a 15-year mission.

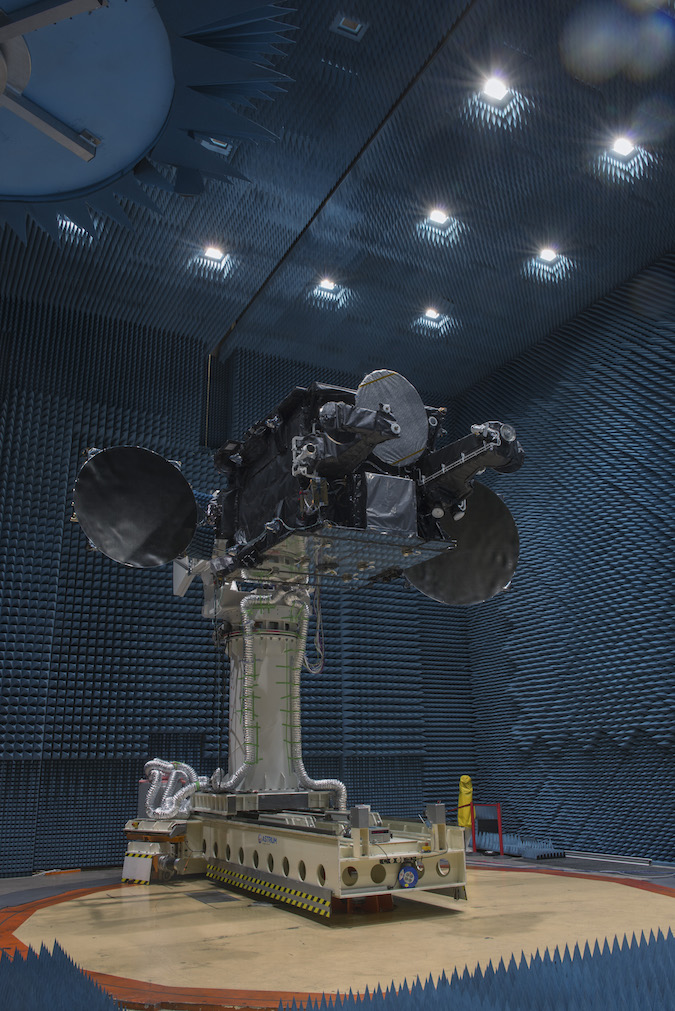

The spacecraft was jointly developed and funded by ESA and OHB in the “SmallGEO” program, aimed at producing a new European medium-class satellite design for commercial and institutional missions. Europe’s two largest spacecraft contractors, Airbus Defense and Space and Thales Alenia Space, primarily build heavier communications satellites.

“We are thrilled and relieved that Hispasat 36W-1 is now on its way,” said Dieter Birreck, the SmallGEO project manager at OHB, in a statement. “The first satellite is always a major stepm particularly in the case of a new specially developed platform in such an important segment as the telecommunications market. We have developed, managed and implemented an integrated design, which we have tested intensively during an eleven-month test campaign. We are very confident of achieving good performance from the end of March.”

The new medium-sized platform, developed with funds from a consortium of European states led by Germany, is the largest spacecraft ever built by OHB, which has staked out a place as the No. 3 satellite-builder on the continent after winning the SmallGEO contract and agreements to produce at least 22 Galileo navigation satellites for the European Commission.

It also gives Germany access to the market to build commercial communications satellites, an area dominated — at least within Europe — by Airbus and Thales plants in France. Hispasat 36W-1 is the first geostationary communications satellite to be developed, assembled and tested in Germany in more than 20 years, according to OHB.

“Hispasat, for us, is a starting point to be active as a visible player in the telecommunication market,” said Andreas Lindenthal, a member of OHB’s management board, in a media briefing before Friday’s launch. “We are proud that we are entering this market together with our partners.”

Hispasat 36W-1 uses a conventional chemical rocket engine for major orbital maneuvers. It will stay in place at 36 degrees west longitude with an electric propulsion system.

An advanced version of the SmallGEO platform, called Electra, will carry an all-electric propulsion system without any liquid hydrazine fuel, making for a more efficient, lighter spacecraft. ESA, OHB and satellite operator SES have partnered on the Electra project, with its first launch in 2021.

OHB has eight more SmallGEO satellites in its current backlog: ESA’s EDRS-C data relay satellite set for launch later this year, the Electra spacecraft, and six Meteosat Third Generation European weather satellites due to start launching in 2019.

The SmallGEO project’s development was not without difficulty.

ESA awarded OHB a contract worth 115 million euros for the first Small GEO platform in 2008. At the time, officials projected the launch of the Hispasat-owned satellite in 2012.

“I do have to admit that we had to learn lessons in the course of the satellite development … and we had a technical issue during the integration of the satellite, so we had to, together our partners Hispasat and ESA, professionally manage those difficulties, which took longer than we had expected,” Lindenthal said in the prelaunch press briefing.

Lindenthal added that the Small GEO platform is now more mature, and he said OHB will be able to offer schedules that are “attractive and accpetable for commercial customers.”

“We are very much pushing for reusing most of the concepts, subsystems and equipment in order to get into the recurring phase, to speed up (construction),” he said.

Hispasat 36W-1’s communications payload features several new technologies supplied by Spanish industry, including a new digital processor and an upgraded reconfigurable antenna design.

The satellite’s telecom system, named RedSAT, was developed by a group of Spanish companies led by Thales Alenia Space España and Airbus Defense and Space’s division in Spain.

“The antenna can be controlled electronically from the Earth and reoriented at any point during the lifespan of the satellite, granting it the flexibility to adapt its coverage to mission changes that may occur after launch, while still in orbit,” Hispasat said in a statement. “The on-board processor is a further step in the evolution of satellites, which can greatly simplify network architecture by performing in space a part of the processing usually carried out on Earth.”

“This system will improve the service provision to end-users allowing greater efficiency by the use of smaller user terminals and the establishment of communication among users in a single ‘satellite hop,’ reducing service latency to one half — which allows optimal real-time applications such as videoconference — and simplifying the network architecture,” Thales Alenia Space said in a press release. “All in all thanks to on-board signal regeneration and the coordinated used of the active antenna.”

Carlos Espinós, Hispasat’s CEO, said last week that his company and Arianespace agreed to switch the launch of Hispasat 36W-1 from the heavy-lift Ariane 5 rocket to the medium-lift Soyuz late last year, permitting a launch in January. The Ariane 5’s manifest was fully booked until later this year.

“With this innovative communications payload, it will be possible to offer oustanding communications services,” Espinós said. “For example, Hispasat 36W-1 will enable backhaul solutions to be rolled out for mobile 2G, 3G and 4G networks in Latin America.

“In the video segment, the satellite will provide continuity services in all coverage areas with line-of-sight to the satellite,” Espinós said. “Likewise, the excellent services of the satellite in the Iberian Peninsula and the Canary Islands will make it easier to provide broadband services, both in the residential and corporate segments, and in mobility.”

Arianespace’s next mission is scheduled for Feb. 14, when an Ariane 5 is set to loft communications satellites to broadcast television to Brazil and for Indonesia.

That flight will be the first of five more Arianespace launches planned through late April, Israel said, setting the stage for a total manifest of 12 missions this year.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.