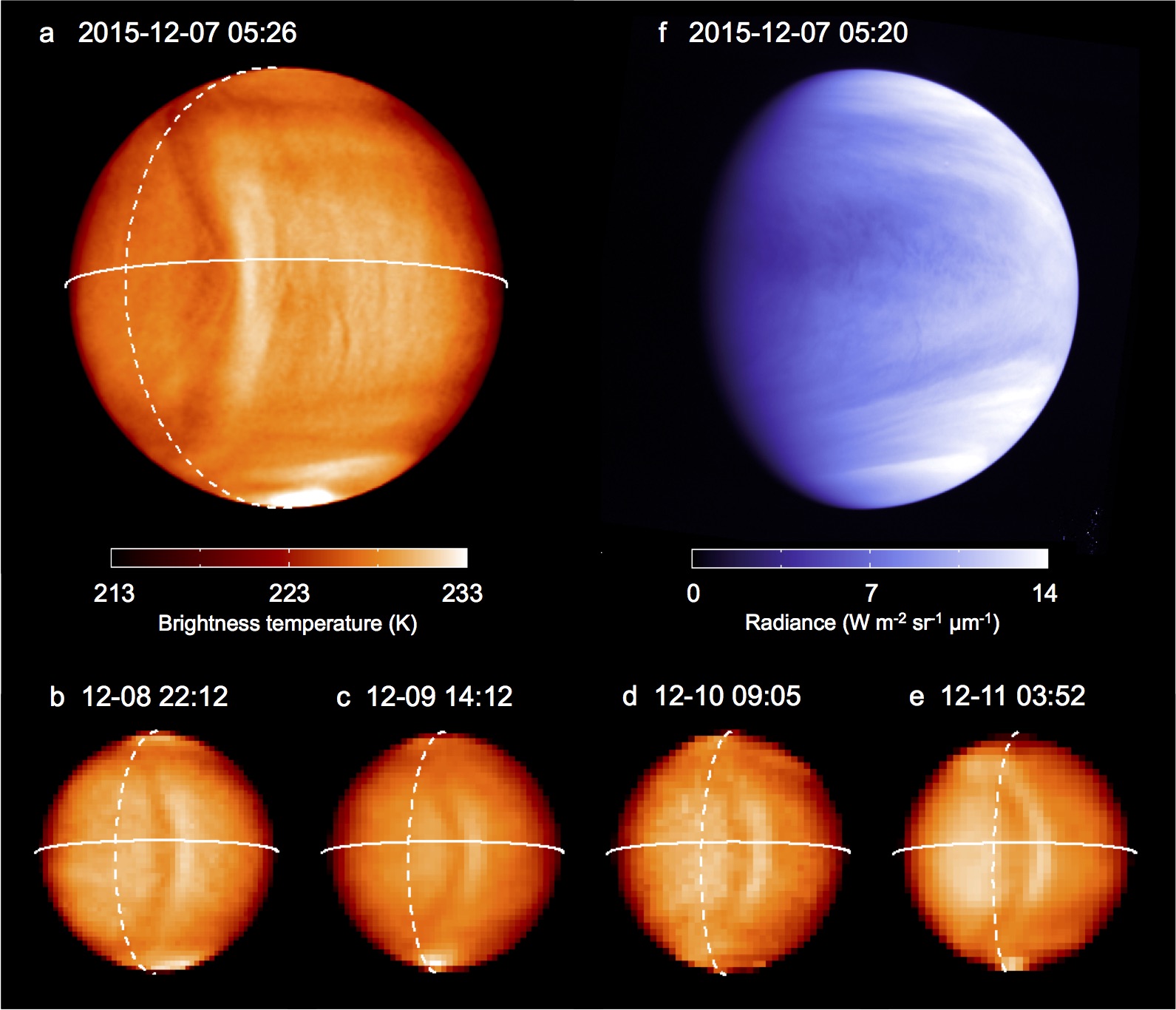

Images from Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft have revealed a gigantic wave in the atmosphere of Venus, and scientists say it may be the largest such feature in the solar system.

The bow-shaped wave ran north-south for 6,000 miles (10,000 kilometers) and stayed stationary for at least four days in December 2015. That is surprising, scientists said, because Venus’s thick sulfuric acid clouds move with a jet stream at more than 220 mph (360 kilometers per hour).

It turns out the atmospheric wave was positioned over Aphrodite Terra, a vast highland region the size of Africa.

While Venus’s “super-rotating” winds whip clouds around the globe at altitudes near 40 miles (65 kilometers), the planet spins slowly, taking 243 Earth days to complete one rotation. On Venus, a day is longer than a year.

“Over several days of observation, the bow-shaped structure remained relatively fixed in position above the highland on the slowly rotating surface, despite the background atmospheric super rotation,” scientists wrote in their report. “We suggest that the bow-shaped structure is the result of an atmospheric gravity wave generated in the lower atmosphere by mountain topography that then propagated upwards.”

The Japanese research team reported their findings Jan. 16 in a paper published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Gravity waves form when a fluid, such as water, plasma or a gas, becomes disturbed. A mountain or island can generate a gravity wave in Earth’s atmosphere when air blows over the obstacle, but the wave on Venus was much larger than any seen on Earth.

Akatsuki’s orbit prevented the spacecraft from watching the wave for about a month after its initial discovery. By mid-January of last year, when the Aphrodite Terra region was again observable from Akatsuki, the wave had disappeared.

The scientists wrote that such a large gravity wave created by highlands on Venus is “difficult to reconcile” with supposed conditions deeper in the planet’s atmosphere near its scorching surface. Researchers suggest the winds in the lower atmosphere of Venus, believed to be much lighter than the winds higher up, may be more variable than previously thought.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Akatsuki spacecraft entered orbit around Venus a few days before the probe’s infrared and ultraviolet cameras spotted the bow wave.

Akatsuki was originally scheduled to start its mission at Venus in December 2010, but a propulsion system problem kept the spacecraft from completing a rocket burn to enter orbit. Five years later, the Japanese-built probe was back in the vicinity of Venus for a second chance.

The maneuver worked, and Akatsuki officially kicked off its science mission last year, and is now the only spacecraft operating around Venus.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.