Two Chinese astronauts are busy with medical experiments and other duties as they near the halfway mark of a month-long stay aboard the Tiangong 2 space lab, according to state media reports.

The medical experiments are one of the top objectives of the mission, which engineers and scientists will use to prepare for longer-duration expeditions aboard China’s planned space station.

Chinese officials have not divulged the daily schedule for Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong, two astronauts who blasted off Oct. 16 inside the Shenzhou 11 space capsule, but government-run media outlets have released regular updates on the progress of the flight.

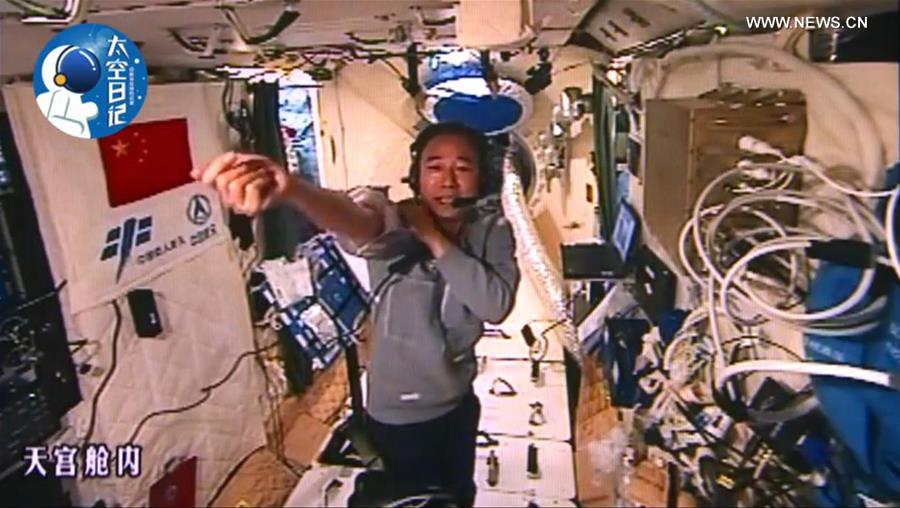

Images recorded inside the Tiangong 2 research module, to which Shenzhou 11 docked two days after its launch, showed Jing and Chen exercising, conducting experiments, and greeting ground teams.

China’s official Xinhua news agency has published a series of posts attributed to the astronauts, providing insights about their tasks and the living conditions aboard Tiangong 2.

An update published Sunday from Chen describes a cardiovascular experiment that is monitoring how the heart and blood vessels change in the microgravity environment of low Earth orbit.

The “gravity-free” experiment includes a blood pressure cuff and sensors to track respiration, Chen writes.

“There is also another, fairly-curious, instrument, which I am sure many of you may not have heard of,” he writes. “It is called a laser Doppler device. This device measures the microcirculation of our blood vessels. As far as I know, this is the first time that China has tested it in space.

“The biggest difference between a (cardiovascular) experiment in space and one on the ground is ultrasound,” Chen writes. “Under zero gravity our organs are slightly displaced. As a result, organs that are usually easy to find on Earth are much more difficult to locate when in space. We have to be aware of this and move the wires accordingly.”

The cardiovascular measurements required the astronauts to wear special suits fitted with the electrocardiogram and ultrasound wires, the blood pressure cuff, and other sensors, according to an Oct. 27 journal update from Jing.

“With this suit, if I want to take my blood pressure, I just zip the suit,” Jing writes. “It is so easy and convenient.”

Jing, Shenzhou 11’s commander, is on his third mission in space. He turned 50 last week.

Chen, 37, is on his first spaceflight.

The astronauts are scheduled to return to Earth around Nov. 18, closing out a 33-day mission, the longest flight by Chinese astronauts to date.

Tiangong 2 is a testbed for China’s planned space station, serving as a proving ground for scientific experiments, engineering tests and other demonstrations before astronauts live aboard the next-generation orbiting research outpost for six-month stints.

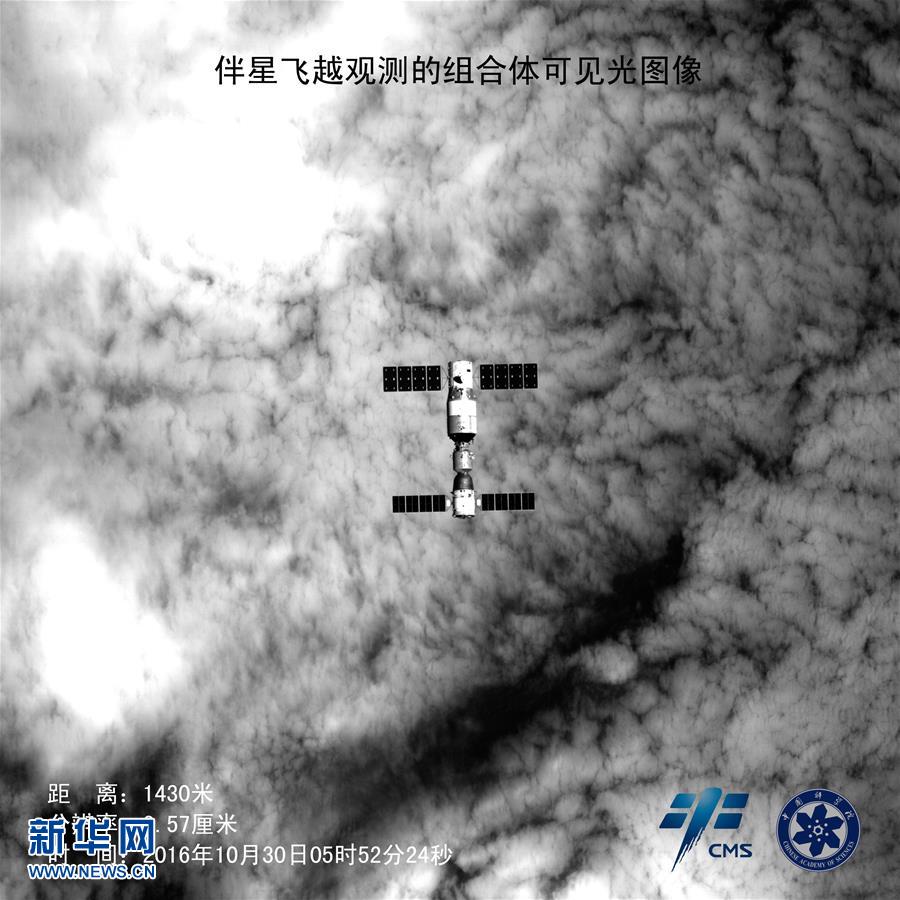

With Shenzhou 11 docked, the combined complex extends more than 60 feet (18 meters) long, forming a mini-space station visible to the naked eye. Skywatchers in the United States have regular evening passes of Tiangong 2 over the next couple of weeks.

Readers interested in observing Tiangong 2 fly overhead can enter their location at heavens-above.com, and search for overflights of the Chinese space lab.

A roving printer-sized satellite deployed from Tiangong 2 earlier in the mission has taken a series of images of the mini-station from below and above. The latest images, captured with Earth as a backdrop, were released by the China Academy of Sciences this week.

Once Shenzhou 11 undocks from Tiangong 2, the module will remain in orbit unoccupied until an unpiloted resupply craft named Tianzhou 1 launches and links up with the space lab in April. Tianzhou 1 will demonstrate in-orbit refueling, another technology China must master before assembling a fully operational space station.

Tiangong 2 carries its own experiment package to continue collecting data once Jing and Chen depart next month.

One of the payloads is named POLAR, and it will detect gamma-ray bursts, the most powerful explosions in the universe.

Developed by scientists in China, Switzerland and Poland, the detector weighs about 70 pounds (30 kilograms) and will help astrophysicists resolve the origin of bright gamma-ray flashes emanating from distant galaxies. Scientists believe most gamma-ray bursts, which can vary in length from milliseconds to hours, occur during supernovas, when stars explode and leave behind a super-dense neutron star or black hole.

“We hope to obtain accurate polarization information of the gamma-ray bursts for the first time ever to better understand the process of how the violent explosions happen,” said Zhang Shuangnan, principal investigator on the POLAR project and a chief scientist at the High Energy Physics Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a report published by Xinhua.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.