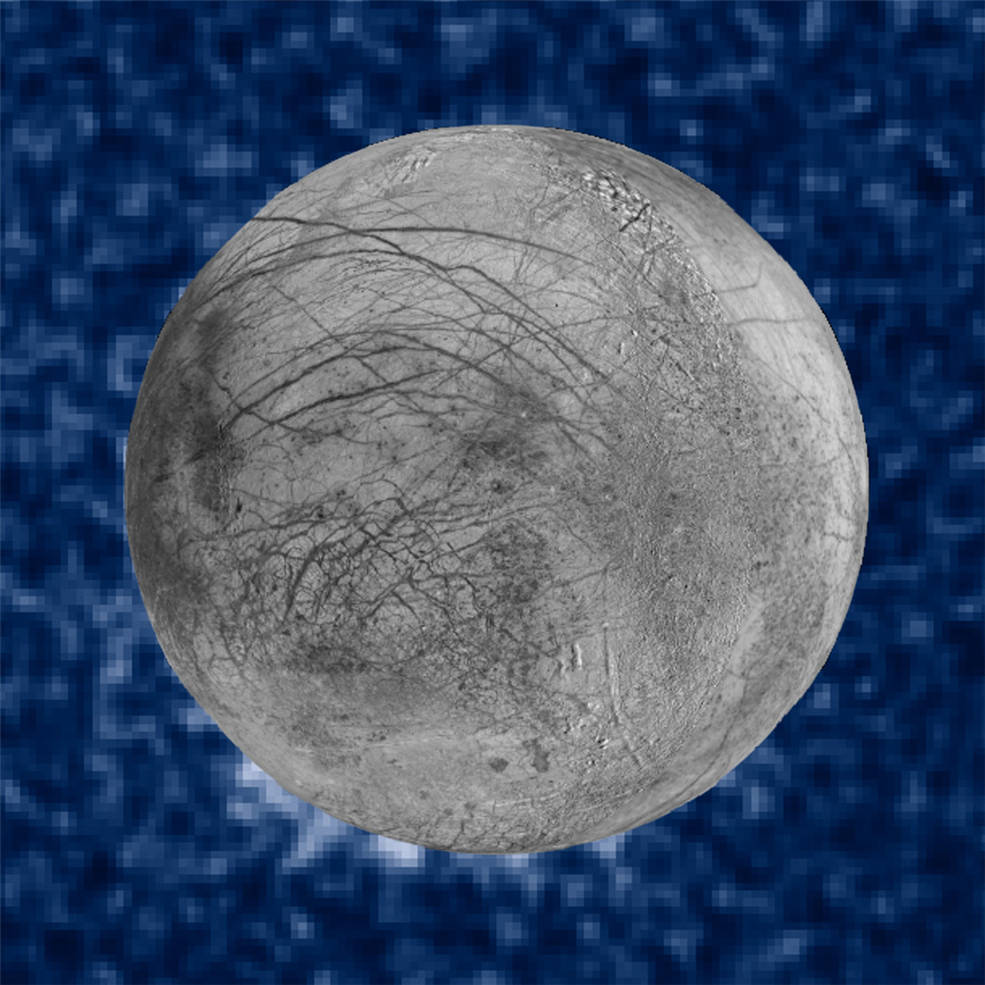

The Hubble Space Telescope has again spotted what appear to be towering plumes of water vapor erupting from Jupiter’s moon Europa, hinting that future spacecraft may be able to sample the hidden sea, a possible abode of life, without having to drill through miles of rock-hard ice, researchers said Monday.

“Today’s results increase our confidence that water and other materials from Europa’s hidden ocean might be on the surface and available for us to study,” said Paul Hertz, director of astrophysics at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

The observations, and earlier Hubble studies that found signs of plumes using a different technique, are at the limits of the space telescope’s capabilities, and researchers cautioned they were not yet ready to say with certainty that water plumes have, in fact, been detected.

But William Sparks, an astronomer with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore who led the latest study, said no other known natural phenomenon can explain the observations.

“I’m not aware of any other plausible natural explanation,” he told reporters. “The only other possible explanation that we’ve been considering is the possibility of some internal instrumental effect.”

That said, the presumed plumes “appear to be real, the statistical signifiance is pretty good and I don’t know of any other natural alternative,” Sparks said.

Europa is one of four bright moons orbiting Jupiter that were discovered by Galileo in 1610. It is roughly the size of Earth’s moon but its composition is very different. Based primarily on data from NASA’s aptly-named Galileo Jupiter orbiter in the 1990s, scientists believe an icy crust covers a vast salt water ocean containing twice the water in all of Earth’s seas.

That ocean is heated and kept from freezing primarily by tidal stresses, the constant squeezing and stretching the moon experiences due to Jupiter’s enormous gravity as it swings around the giant planet every 3.5 days.

Given water, energy and, possibly, organic compounds, the sub-surface ocean is a possible abode of life and is therefore of major interest to astrobiologists. NASA is in the initial stages of developing a spacecraft to explore the moon through repeated flybys in the 2020s.

A major question mark has been how thick Europa’s crust might be and how difficult it might be to one day drill through it to collect samples of the ocean below. But if the plumes are eventually confirmed, as appears likely, drilling might not be necessary.

“If there are plumes emerging from Europa, it’s significant because it means we may be able to explore that ocean for organic chemicals, or even signs of life, without having to drill through unknown miles of ice,” Sparks said.

In 2012, a team of researchers using the Hubble Space Telescope’s imaging spectrograph spotted what appeared to be water vapor more than 100 miles above Europa’s south pole.

Sparks’ team used a different technique, observing the limb of the moon in ultraviolet light as it passed in front of Jupiter. During three of 10 observations, background light was absorbed by what the researchers concluded were likely plumes of water vapor towering 125 miles above the surface.

The two techniques have not yet seen plumes at the same time, suggesting they may be sporadic and short lived. Additional Hubble observations are being analyzed, more are planned and NASA’s much more powerful James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in November 2018, will bring even more sensitive instruments to bear.

“Europa’s ocean is considered to be one of the most promising places that could potentially harbor life in the solar system,” Geoff Yoder, acting associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a statement. “These plumes, if they do indeed exist, may provide another way to sample Europa’s subsurface.”