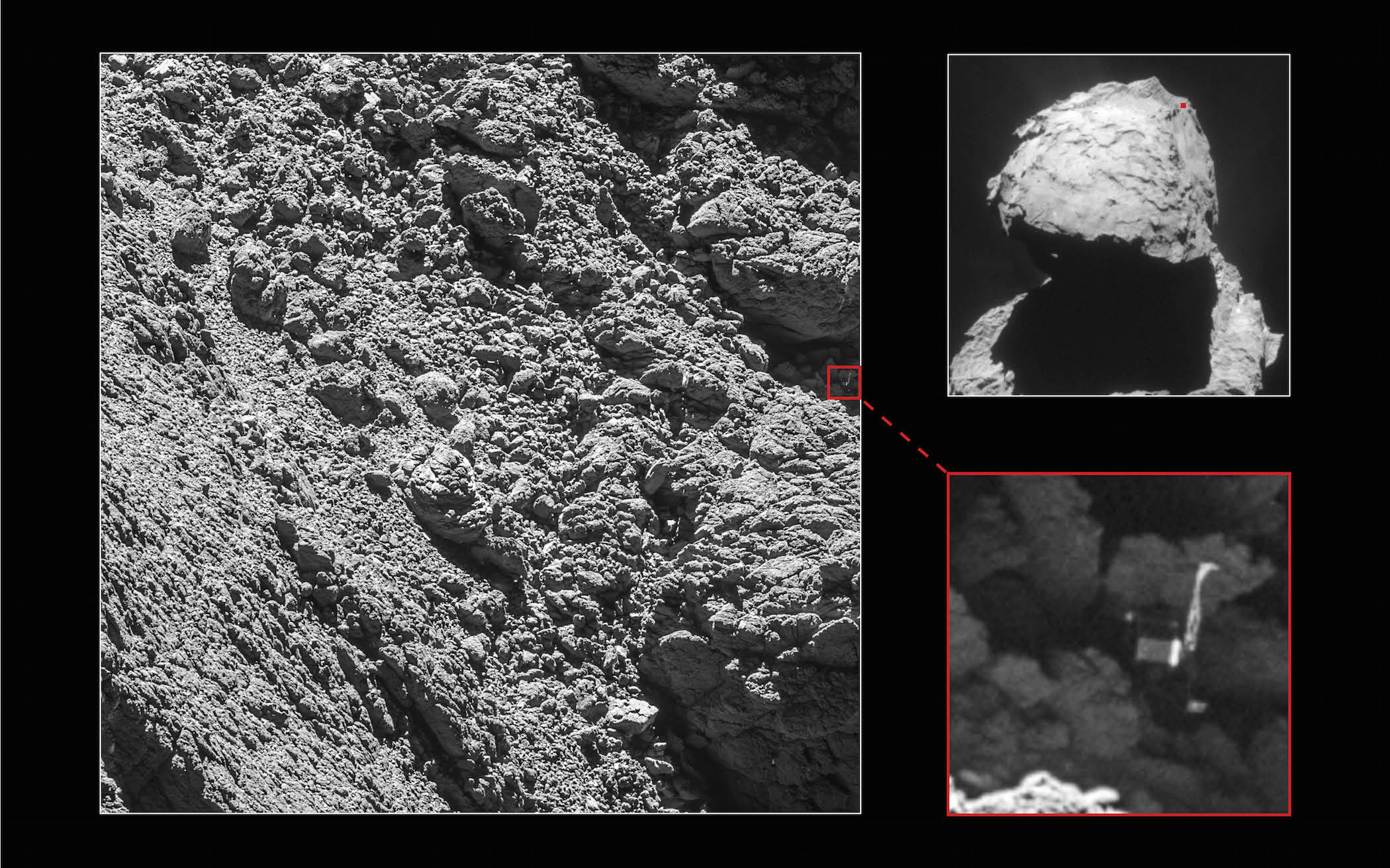

A Rosetta Navigation Camera image taken on 16 April 2015 is shown at top right for context, with the approximate location of Philae on the small lobe of comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko marked. Credit: Main image and lander inset: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA; context: ESA/Rosetta/NavCam – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

Scientists culling through images taken last week by the Rosetta spacecraft’s sharp-eyed science camera have finally pinpointed the exact spot the Philae lander settled on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko after a daring descent nearly two years ago, the European Space Agency announced Monday.

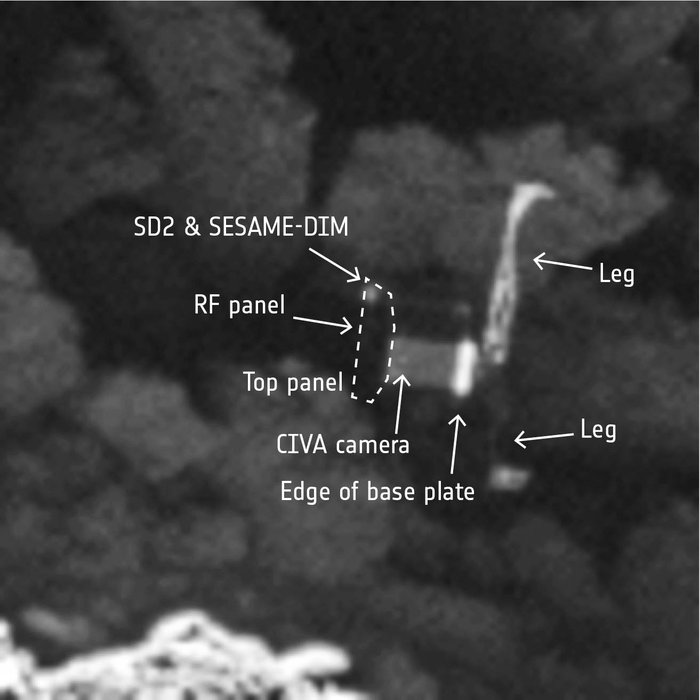

Less than a month before Rosetta ends its two-year survey of the comet, the probe’s OSIRIS camera found Philae on Friday nestled amid a rugged landscape marked with boulders and cliffs. The imagery confirmed the lander is sitting on its side in the shadow of a nearby rock face, illustrating why Philae lost power from its solar panels within three days of touchdown.

The lander’s orientation and location also made it difficult to establish communications after Philae came out of hibernation in June 2015. Ground controllers last heard from Philae in July 2015, and then gave up hope of re-activating the comet research station earlier this year.

“With only a month left of the Rosetta mission, we are so happy to have finally imaged Philae, and to see it in such amazing detail,” said Cecilia Tubiana, a member of the OSIRIS imaging team.

ESA said Tubiana was the first person to see the images of Philae when they were downlinked to Earth on Sunday. Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera took the pictures when the craft passed within 9,000 feet (2.7 kilometers) of the duck-shaped comet.

“After months of work, with the focus and the evidence pointing more and more to this lander candidate, I’m very excited and thrilled that we finally have this all-important picture of Philae sitting in Abydos,” said Laurence O’Rourke, coordinator of ESA’s lander search team charged with finding Philae’s landing site on comet 67P.

Philae detached from the Rosetta mothership Nov. 12, 2014, on a slow-speed collision course with the comet. After a seven-hour descent, Philae reached the relatively flat landing zone picked by mission scientists right on target, but all three of the probe’s landing aids failed to engage at touchdown.

Philae carried a upward-facing rocket thruster to help push the lander on to comet 67P’s surface, along with harpoons and ice screws to anchor the craft’s three landing legs to the comet. None of those systems worked as designed.

Comet 67P’s tenuous gravity was not strong enough to keep Philae on the surface, and the probe bounced back into space and tumbled for two hours up to 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) off the jagged space rock, hitting the comet again before settling at its final resting place in a region dubbed Abydos, keeping with the Rosetta team’s ancient Egyptian naming theme.

But the nearly $250 million (220 million euro) lander mission, led by Germany, still returned valuable science data, the first observations ever collected from the surface of a comet.

In the first three days after landing, Philae took a panoramic image, measured the composition and properties of the comet’s surface, discovered organic molecules residing on the diminutive world, and conducted radio transponder experiments with Rosetta to help study the comet’s interior structure.

But Philae was wedged in shadow at its unexpected landing site and unable to recharge its batteries with the craft’s body-mounted solar panels. The lander’s batteries drained within three days.

Last year, when comet 67P approached perihelion, the closest point to the sun in its nearly 6.5-year orbit, engineers restored communication with Philae as it absorbed more solar energy. But the radio links were intermittent, and Philae went silent in July 2015.

Officials suggested the lander may have had a problem with its transmitter.

The ground team attempted to find the lander by analyzing the radio signals bounced between Rosetta and Philae, and by taking high-resolution pictures of the comet in hopes the surface station would be visible.

Philae’s radio was not powerful enough to communicate directly with Earth, so Rosetta acted as a relay satellite to hand off science data and commands passing each way. The radio signals provided hints to Philae’s distance from the Rosetta spacecraft parked in orbit around the comet, and experts used that information to triangulate the lander’s location.

It turns out Philae is sitting just where the ground team expected. But until last weekend, officials could not say for sure.

“This wonderful news means that we now have the missing ‘ground-truth’ information needed to put Philae’s three days of science into proper context, now that we know where that ground actually is,” said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

Time was running out in the hunt for Philae. Rosetta is scheduled to make a controlled crash into the comet Sept. 30, before it also runs out of electrical power as comet 67P drives farther from the sun, where temperatures are cold and there is insufficient light to keep the spacecraft running.

The comet will reach aphelion, a point beyond Jupiter’s orbit too far for Rosetta’s solar panels to convert enough sunlight into electricity.

Mission managers concluded Sept. 30 was the best time to place Rosetta on the comet, when it still has enough electricity to make the plunge with all its science instruments turned on to gather unprecedented information on the environment within hundreds of feet of the surface.

Rosetta’s designers never envisioned landing the spacecraft. Fitted with two solar wings spanning 105 feet (32 meters) tip-to-tip, Rosetta will likely be damaged at touchdown — even at slow speed — and ground controllers plan to program the on-board flight computer to turn off the probe’s transmitter when it reaches the comet.

The complex maneuvers required to set up for Rosetta’s landing at the end of September are what allowed for the up-close snapshot of Philae. The orbiter is spiraling closer and closer to comet 67P in advance of the Sept. 30 landing.

Once Rosetta is gone, scientists would have no hope of ever finding Philae.

“This remarkable discovery comes at the end of a long, painstaking search,” said Patrick Martin, ESA’s Rosetta mission manager, in a statement. “We were beginning to think that Philae would remain lost forever. It is incredible we have captured this at the final hour.”

Rosetta is heading for a landing target on a different section of comet 67P, where scientists discovered open pits that may be the source of jets and outbursts that launched clouds of ice and dust into space last year.

“Now that the lander search is finished we feel ready for Rosetta’s landing, and look forward to capturing even closer images of Rosetta’s touchdown site,” said Holger Sierks, principal investigator of the OSIRIS camera.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.