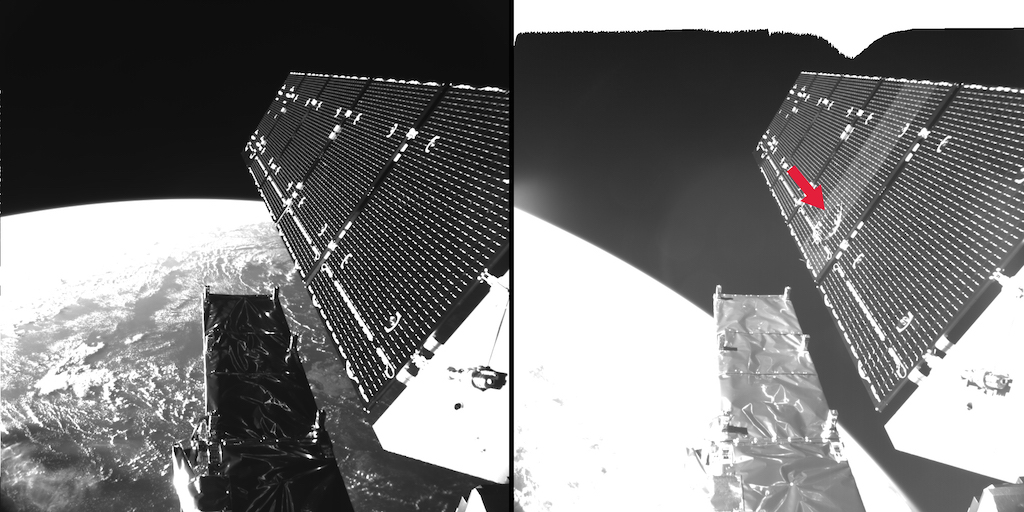

A minuscule particle of orbital debris or a pebble of space rock struck Europe’s Sentinel 1A radar imaging satellite Aug. 23, officials said Wednesday, leaving an imprint nearly twice the size of a basketball on one of the spacecraft’s solar panels.

The high-speed impact caused no major problems for the Earth observation satellite, which continues to operate normally. But ground controllers noticed a “sudden” small reduction in the power generated by one of Sentinel 1A’s solar arrays at 1707 GMT (1:07 p.m. EDT) Aug. 23, along with slight changes in the orbit and orientation of the spacecraft sailing in orbit 435 miles (700 kilometers) above Earth, the European Space Agency said in a press release.

Engineers suspected the culprit was an impact by a piece of space junk or a micrometeoroid.

“Such hits, caused by particles of millimeter (.04 inch) size, are not unexpected,” said Holger Krag, head of the space debris office at ESA’s establishment in Darmstadt, Germany. “These very small objects are not trackable from the ground, because only objects greater than about 5 centimeters (2 inches) can usually be tracked and, thus, avoided by maneuvering the satellites.”

Components of the International Space Station have suffered impacts from space junk before, and space shuttles that returned to Earth sometimes came home with scars from orbital debris. An Iridium communications satellite collided with a defunct Soviet-era military spacecraft in 2009, destroying both platforms in a shower of debris.

What is unusual is Sentinel 1A’s ability to conduct a self-inspection.

The satellite carries on-board cameras pointed at its solar wings. Engineers used the cameras to monitor the extension of the satellite’s solar arrays after its launch in April 2014, a deployment more complicated than normal because Sentinel 1A carries a large C-band radar array.

The cameras were switched off soon after the solar panels deployed, but controllers turned the devices back on to investigate the cause of the power loss. They found evidence of an impact on the second segment of one of the craft’s two solar array wings.

“In this case, assuming the change in attitude and the orbit of the satellite at impact, the typical speed of such a fragment, plus additional parameters, our first estimates indicate that the size of the particle was of a few millimeters (approximately 0.2 inches or less),” Krag said in a statement.

Experts are not sure of the origin of the particle.

“Analysis continues to obtain indications on whether the origin of the object was natural or man-made,” Krag said. “The pictures of the affected area show a diameter of roughly 40 centimeters (16 inches) created on the solar array structure, confirming an impact from the back side, as suggested by the satellite’s attitude rate readings.”

Designed for a seven-year lifetime, Sentinel 1A is part of the European Commission’s Copernicus program, a multibillion-dollar network of Earth observation satellites designed to monitor the environment, natural disasters, vegetation, and the health of the world’s oceans.

ESA operates the Sentinel 1A satellite on behalf of the commission, the executive body of the European Union.

“The power reduction is relatively small compared to the overall power generated by the solar wing, which remains much higher than what the satellite requires for routine operations,” ESA said in a statement about Sentinel 1A’s collision.

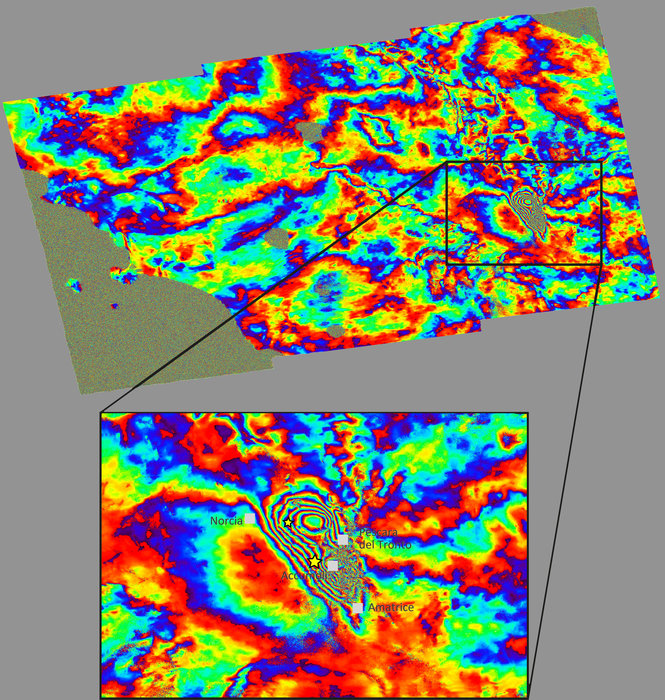

The C-band radar on Sentinel 1A can see through clouds and produce images of Earth day and night. The instrument is tuned to track sea ice, oil spills, marine winds, waves and currents, land deformation, and help authorities respond to disasters like floods and earthquakes.

Scientists analyzed imagery from the Sentinel 1A and Sentinel 1B satellites in the aftermath of the Aug. 24 earthquake in central Italy, revealing how much land around the epicenter sunk and moved sideways during the shaking.

Radar data from the Sentinel 1 missions allow experts to “examine the ground displacement caused by this earthquake and develop the scientific knowledge of quakes,” ESA said in a press release.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.