A Chinese rover sent to the moon in 2013 has stopped operating, officials announced Wednesday, ending a groundbreaking 31-month mission that made discoveries in lunar geology and catapulted China’s space program to new heights.

The long-lived Yutu rover lost its mobility about a month after landing, but it kept returning science data. Ground controllers stayed in contact with Yutu, which means “jade rabbit” in Chinese, until some time in the last few days.

China’s state-run Xinhua news agency reported Wednesday that the six-wheeled has stopped operating. Reports suggested the rover may have succumbed to cold temperatures during the two-week lunar night that began July 28.

Against long odds, Yutu survived frigid conditions on 32 previous nights, weathering temperatures as low as minus 300 degrees Fahrenheit — about minus 180 degrees Celsius — for 14 days at a time.

The solar-powered rover went into hibernation at each sunset, and it carried plutonium heaters to keep internal electronics warm.

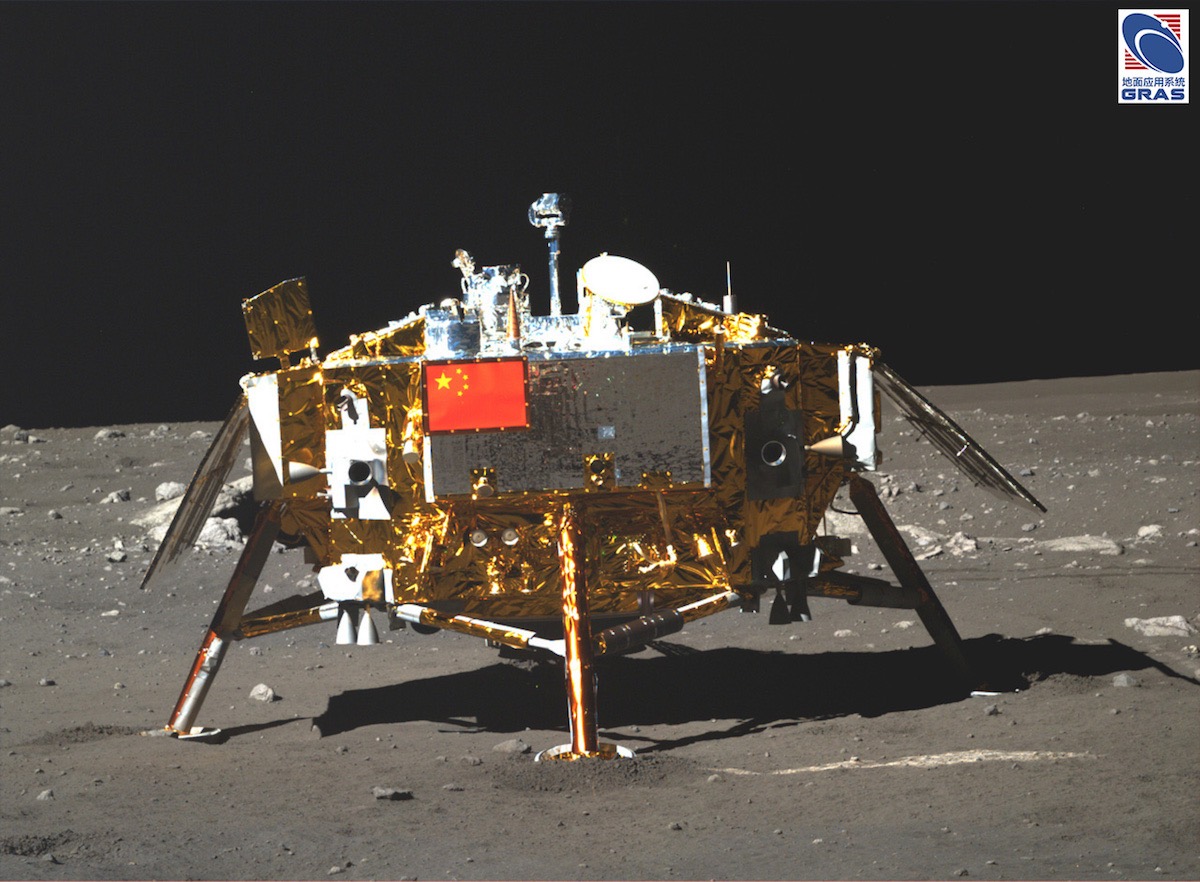

Stowed aboard China’s Chang’e 3 landing platform, Yutu arrived in the moon’s Mare Imbrium region, a dark feature carved out by a massive meteorite 3.9 billion years ago, with a successful propulsive touchdown Dec. 14, 2013.

The Chang’e 3 mission achieved the first “soft landing” on the moon since the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 spacecraft completed a robotic lunar sample return flight in 1976, and it was China’s first landing on another world.

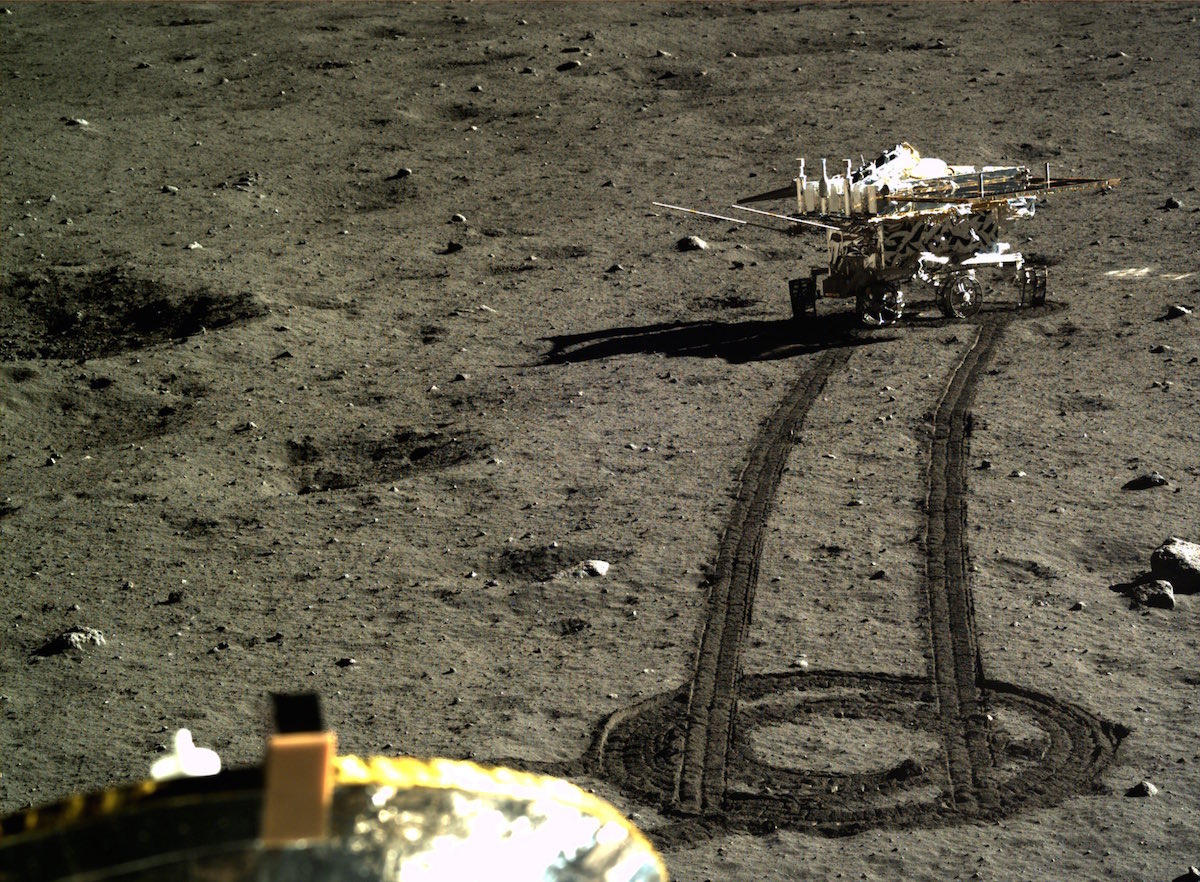

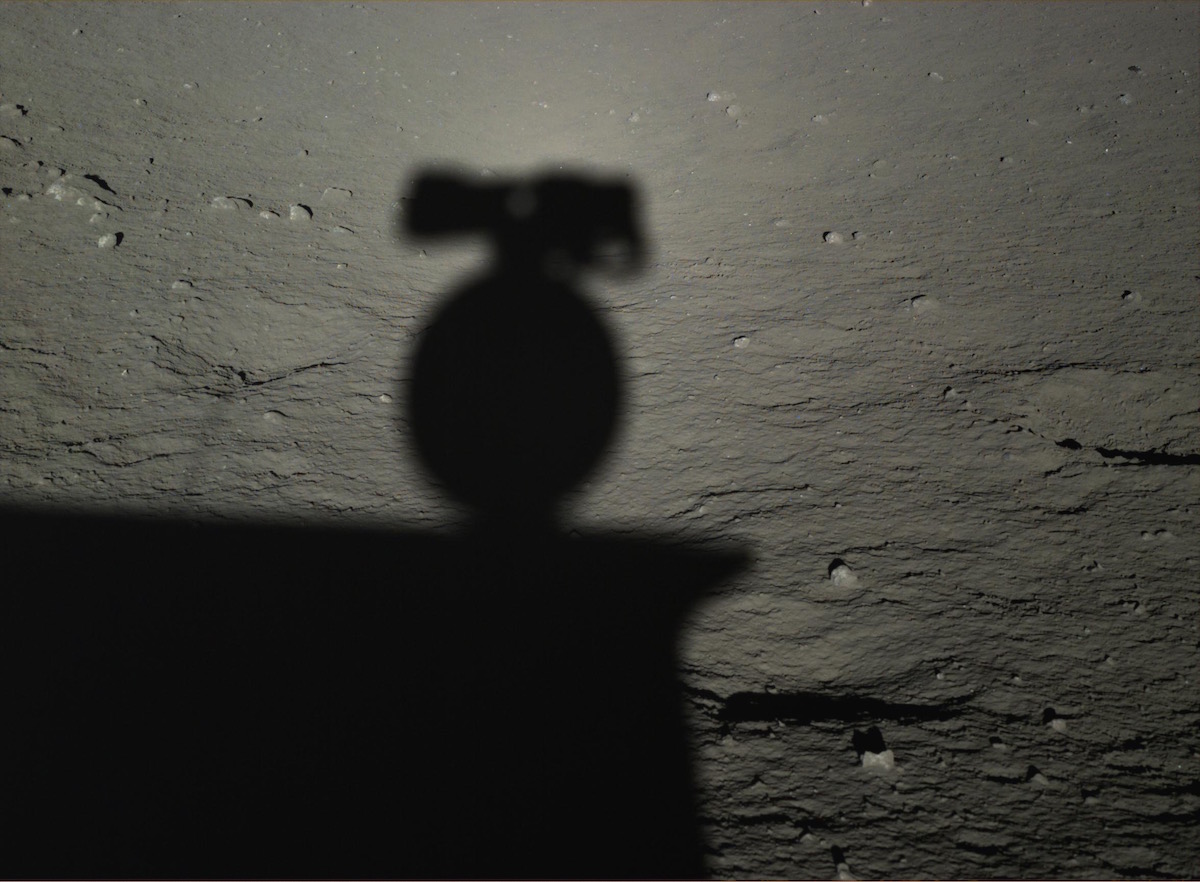

Yutu disembarked the stationary landing platform soon after arriving on the moon, and logged more than 300 feet (about 100 meters) of driving before a problem immobilized the robot. The craft continued to collect scientific measurements, and survived 31 months — more than 10 times longer than its three-month design life — before its recent failure.

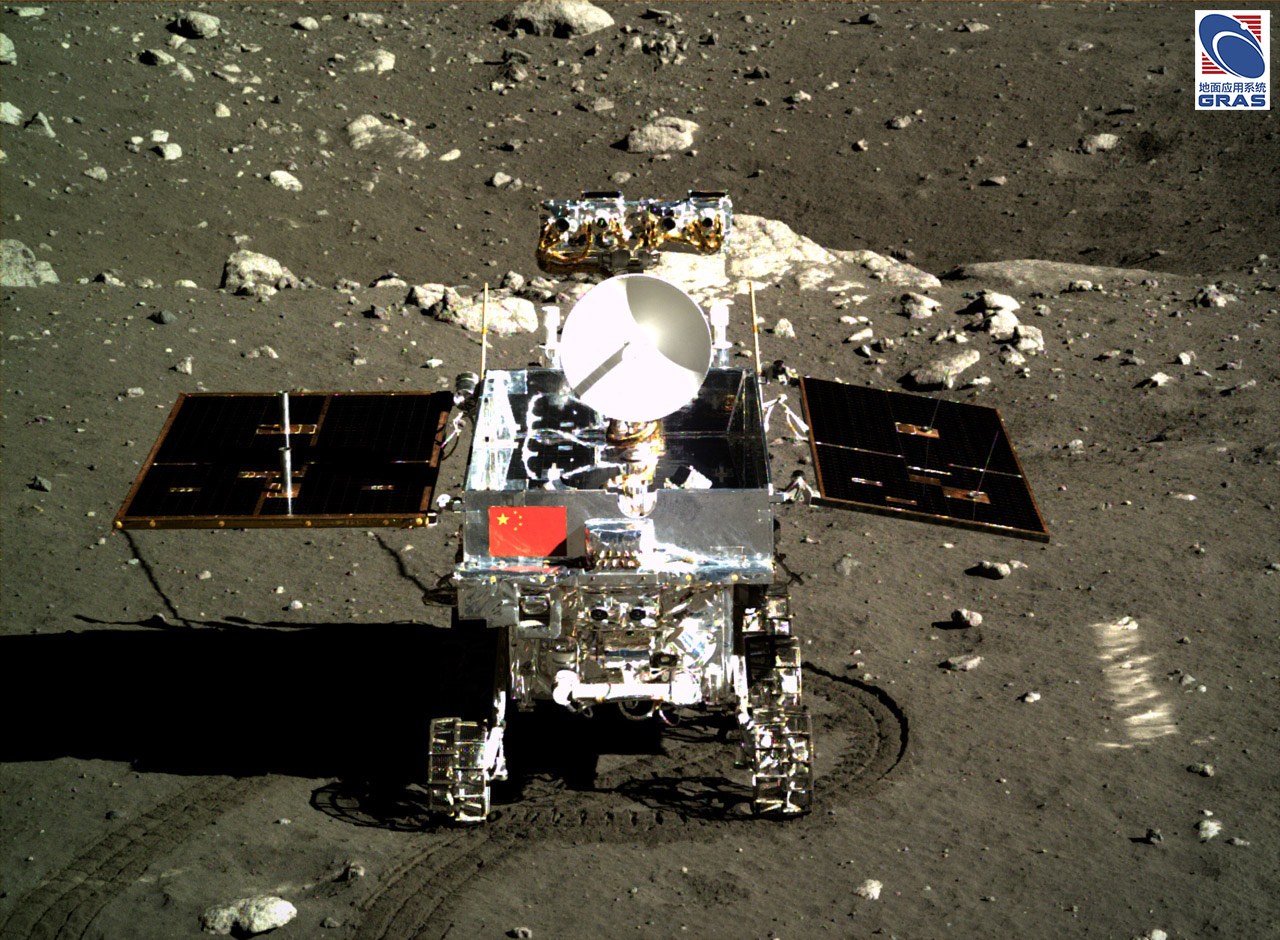

The rover weighs about 308 pounds (140 kilograms) and stands about 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, smaller than NASA’s Opportunity and Curiosity rovers currently exploring Mars.

Yutu and the Chang’e 3 lander snapped dramatic photos of each other, showing each craft backdropped against the stark charcoal-colored lunar landscape.

In a first for China, scientists have publicly released all processed data from the Chang’e 3 mission. Raw data products embargoed because they are still being analyzed by the Chinese science team, officials said.

Chinese managers say the mission returned 7 terabytes of data.

The Chang’e 3 mothership, fitted with its own set of cameras and sensors, is apparently still operating well beyond its 12-month life expectancy.

One result from the mission was Yutu’s discovery of a new type of rock, a basalt different than samples returned from the moon by Apollo astronauts and the Soviet-era Luna landers.

Chang’e 3 touched down near the relatively fresh Zi Wei crater on a plain overlaid with younger lava flows than regions visited by the Apollo and Luna missions in the 1960s and 1970s.

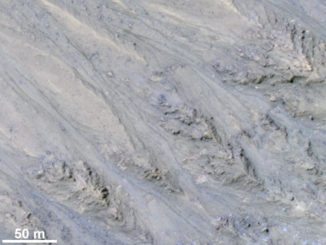

Yutu’s ground-penetrating radar, the first instrument of its type to fly to the moon, peered beneath the lunar surface and found the top basalt layer to be surprisingly thin and pristine.

“This indicates that until the late period, about two billion years since it was born, there were still huge amounts of magma that were erupting,” said Lin Yangting, a researcher from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a report by state-owned China Radio International. “This shows that the activity of the magma on the moon lasted longer than expected.”

The new type of basalt detected by Yutu indicates the moon retained magma until at least 3 billion years ago, and perhaps slightly more recently, in the Mare Imbrium region.

“The diversity tells us that the moon’s upper mantle is much less uniform in composition than Earth’s,” said Bradley Jolliff, a professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, who analyzed the Yutu dataset. “And correlating chemistry with age, we can see how the moon’s volcanism changed over time.”

For the first time, scientists can also match up-close measurements from Yutu with signals from instruments aboard remote sensing craft, such as NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The calibration could yield improvements in studying other regions on the moon without landing there.

“We now have ‘ground truth’ for our remote sensing, a well-characterized sample in a key location,” Jolliff said in a press release last year. “We see the same signal from orbit in other places, so we now know that those other places probably have similar basalts.”

Chang’e 3 is China’s third lunar mission, launching after a pair of orbiters went to the moon in 2007 and 2010.

China is preparing for its next lunar probe, Chang’e 5, to launch in 2017. That spacecraft will land on the moon, gather samples, and blast off again to return the specimens to Earth.

Another lunar lander, called Chang’e 4, is also set for liftoff in 2018 to conduct the first landing on the far side of the moon. It is based on a spare spacecraft developed for Chang’e 3.

China plans to launch a separate orbiter to go on station above the far side of the moon to relay radio signals between the Chang’e 4 lander and Earth.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.