SpaceX and SES, owner of a 5.8-ton commercial telecom satellite poised for launch from Cape Canaveral on Wednesday, struck a deal to tweak the Falcon 9 rocket’s standard launch profile to give the SES 9 spacecraft a stronger push toward its operating post more than 22,000 miles above Earth.

The Boeing-built television broadcasting satellite will get an additional burst of energy from the Falcon 9’s second stage engine after Wednesday’s liftoff from Cape Canaveral’s Complex 40 launch pad set for 6:46:14 p.m. EST (2346 GMT).

The change shaves the time required for the craft’s own propulsion system to maneuver into position to begin a 15-year mission beaming video programming and data services across the Asia-Pacific.

Officials described the agreement, first disclosed without details earlier this month, in a meeting with reporters at Cape Canaveral on the eve of SES 9’s launch.

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of Tuesday’s media roundtable with Martin Halliwell. Become a member today and support our coverage.

SES 9 has waited nearly a year for a launch slot aboard the Falcon 9, which was grounded six months after a failure last year and has struggled to meet a jam-packed manifest of launches for NASA and commercial satellite operators.

But Martin Halliwell, chief technology officer of SES, sang SpaceX’s praises in a preflight press briefing at Cape Canaveral on Tuesday.

“I know we’re a little bit late, but we can live with that,” he said. “We’ll move on. What’s most important is that we get the perfect mission.”

SES is the world’s largest operator of geostationary communications satellites, and the Luxembourg-based company approached SpaceX for some relief after the launch delay.

“We sat with SpaceX and said, ‘Guys, how can you improve our mission profile? How can you get us to orbit a little bit quicker?’ We have agreed with SpaceX that we will change the mission from a guidance controlled shutdown of the second stage to what we call a minimum residual shutdown of the upper stage,” Halliwell said.

In plain speak, the adjustment is a change in the Falcon 9 rocket’s control logic.

Instead of programming a target orbit into the rocket’s guidance system, the Falcon 9’s second stage will burn its single Merlin engine until the launcher’s supply of kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants are nearly gone.

“We’re going to burn the motor on the second stage for a few more seconds,” Halliwell said. “That’s all it really means.”

SES 9’s launch weight is 11,620 pounds, or about 5,271 kilograms, according to Halliwell. That is heavier than the Falcon 9 rocket’s advertised lift capacity to geosynchronous transfer orbit, an elliptical path around Earth that serves as a drop-off point for communications satellites heading for positions 22,300 miles (36,000 kilometers) above the equator, a popular location for powerful broadcast platforms.

Geosynchronous transfer orbits targeted by satellite launchers typically have an apogee, or high point, of at least 22,300 miles and a low point a few hundred miles above Earth.

Halliwell said SES’s contract with SpaceX called for the rocket to deploy SES 9 into a “sub-synchronous” transfer orbit with an apogee around 16,155 miles (26,000 kilometers) in altitude. Such an orbit would require SES 9 to consume its own fuel to reach a circular 22,300-mile-high perch, a trek that Halliwell said was supposed to last 93 days.

The change in the Falcon 9’s launch profile will put SES 9 into an initial orbit with an apogee approximately 24,419 miles (39,300 kilometers) above Earth, a low point 180 miles (290 kilometers) up, and a track tilted about 28 degrees to the equator, Halliwell told Spaceflight Now.

The exact orbit figures will depend on the Falcon 9’s performance.

“We’re going slightly super-synchronous, so slightly above our final required altitude,” Halliwell said. “This will allow us to be able to reduce the amount of propellant, both electric xenon and also bi-propellant, that we actually use for the final orbit-raising.”

Such an orbit is more in line with standard practice in the launch business.

“Initially, it was going to take about 93 days to get to orbit, but those few more seconds of burn will bring us down to about 45 days, so we should be in operational service towards the end of May or right at the very beginning of June,” Halliwell said. “That is a big deal for us.”

SES 9 has a hybrid propulsion package using liquid hydrazine fuel to complete most of the maneuvers necessary to reach its equator-hugging orbit 22,300 miles high. A xenon-fueled electric propulsion system, utilizing low-impulse but ultra-efficient thrusters, will fine-tune SES 9’s orbit and keep it in position for its 15-year service life.

The electric thrusters take longer to move the satellite than conventionally-fueled rockets, which typically complete put communications spacecraft in their final orbits within a few weeks of launch.

At geostationary altitude, SES 9’s orbital velocity will match the rate of Earth’s rotation, causing the satellite to hover over a fixed location at the intersection of the equator and 108.2 degrees east longitude.

From its high-altitude perch, SES 9’s Ku-band communications payload will broadcast television programming across Southeast Asia, replacing the NSS 11 satellite launched on a Proton rocket in 2000. SES 9 will be the company’s largest satellite serving the Asian market, according to Halliwell.

Up to 22 million homes across the Asia-Pacific, clustered in countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines and India, will receive high-definition television programming via SES 9.

The new telecom station will also connect ships in the Indian Ocean to communications networks and provide in-flight entertainment for airline passengers in Southeast Asia.

SES 9 is one of seven satellites in development by SES, a combined investment Halliwell said is worth up to $1.8 billion. He declined to identify the cost of SES 9 itself.

Five of the satellites are assigned to fly on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket family.

Halliwell said SES engineers embedded with SpaceX in the aftermath of last year’s Falcon 9 launch mishap, which was blamed on a faulty strut that led to an overpressure in the rocket’s second stage.

“In adversity, you really see how good a company is,” Halliwell said.

He said SES engineers analyzed Falcon 9 data alongside SpaceX — access that is limited to U.S. citizens due to export control laws — and came away pleased with the results of the investigation and the first flight of an upgraded Falcon 9 model in December.

“We have our own people embedded (at SpaceX headquarters) in Hawthorne working together with SpaceX, and we have access to the data through our U.S. citizens, which was really unprecedented,” Halliwell said. “It gave us great confidence moving forward.”

Wednesday’s launch will be the second flight the latest iteration of the Falcon 9, featuring enlarged fuel tanks and Merlin 1D engines rated for higher thrust. The upgraded Falcon 9 also burns propellants chilled to colder temperatures than normal, an innovation that results in denser fuel.

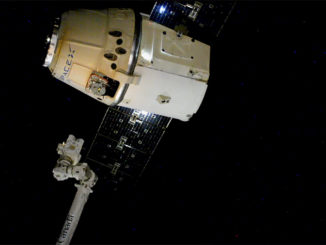

SpaceX aims to recover the Falcon 9’s first stage booster on a landing ship stationed 400 miles (650 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral in the Atlantic Ocean, the latest experiment in the company’s bid to turn the rocket into a partially reusable launcher.

The company says a successful landing is not expected due to the extreme speeds required for Wednesday’s launch.

The first stage will fire its nine engines more than two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff from Cape Canaveral, reaching a top speed of between 5,000 and 5,600 mph (8,000-9,000 kilometers per hour), SpaceX said.

That is too fast to permit the rocket to turn around and fly back to a landing zone at Cape Canaveral as a Falcon 9 booster did in December, when it carried a relatively light payload of 11 small satellites into an orbit a few hundred miles up.

The Falcon 9 first stage on the Dec. 21 flight reached a maximum velocity of about 3,100 mph (5,000 kilometers per hour), SpaceX said.

SpaceX and SES officials reported no technical concerns going into Wednesday’s countdown, but the launch team will monitor brisk winds and cloudy weather predicted over Cape Canaveral during the launch window. There is a 60 percent chance weather will cooperate for liftoff Wednesday.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.