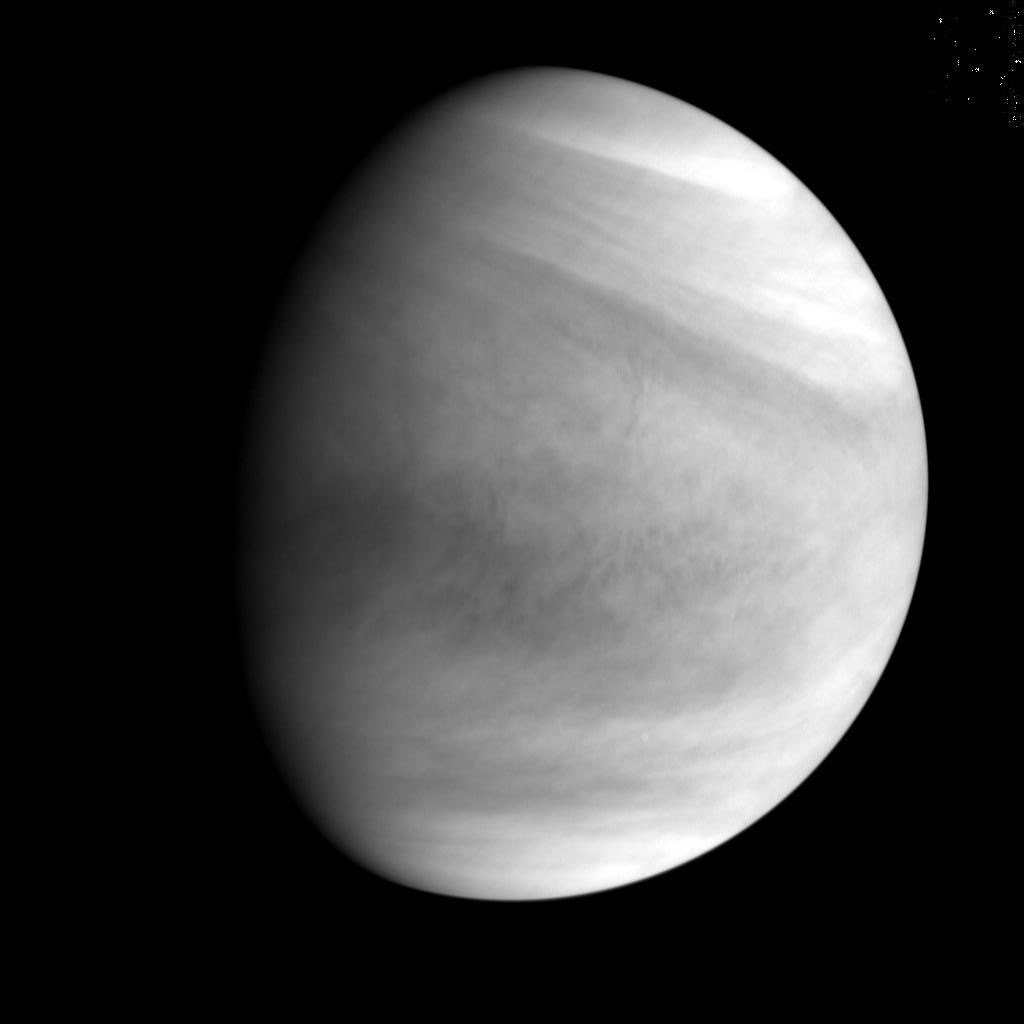

Japanese scientists released Wednesday the first views of Venus captured by the Akatsuki spacecraft after arriving in orbit this week, setting the stage for regular observations of the planet’s blistering atmosphere over the next few years.

The Japanese space agency — JAXA — also confirmed Akatsuki is in a good orbit around Venus after a 20-minute firing of four of the spacecraft’s maneuvering thrusters beginning at 2351 GMT (6:51 p.m. EST) Sunday.

Engineers said Monday the make-or-break rocket burn appeared to go as planned, but it took two days for ground stations to carefully monitor Akatsuki’s trajectory and verify the parameters of its orbit.

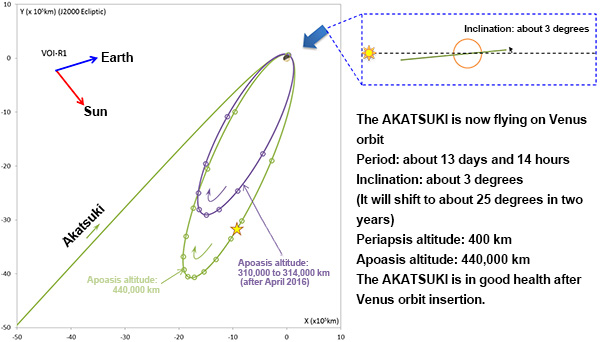

The thruster firing placed Akatsuki in an elongated elliptical orbit ranging as far as 440,000 kilometers (273,000 miles) from Venus. At the low point of its orbit, Akatsuki passes about 400 kilometers (248 miles) above the planet, JAXA officials said Wednesday.

The orbit is slightly lower than anticipated, an indication that the maneuver outperformed expectations, generating extra impulse to drive Akatsuki on a path closer to Venus, officials said.

It takes about 13 days and 14 hours for Akatsuki to make one lap around the planet, down from the planned 15-day orbit time.

The spacecraft is orbiting Venus in the same direction of the planet’s rotation, at a three-degree angle to its equator. The inclination value is almost right on the mark compared to predictions.

Akatsuki entered orbit early Monday after a five-year sojourn through the solar system, a voyage that was extended after the craft missed an opportunity to enter orbit around Venus in December 2010. The mishap meant Akatsuki had to weather more extreme temperatures than planned, and engineers commanded the orbiter to fire its secondary thrusters for the critical Venus arrival maneuver after the failed 2010 burn damaged its main engine.

Engineers were cautiously optimistic as Akatsuki sped toward Venus, but managers acknowledged the maneuver was risky.

But the burn occurred without any problems, making Akatsuki the only space probe currently operating at Venus, and Japan’s first spacecraft to go into orbit around another planet.

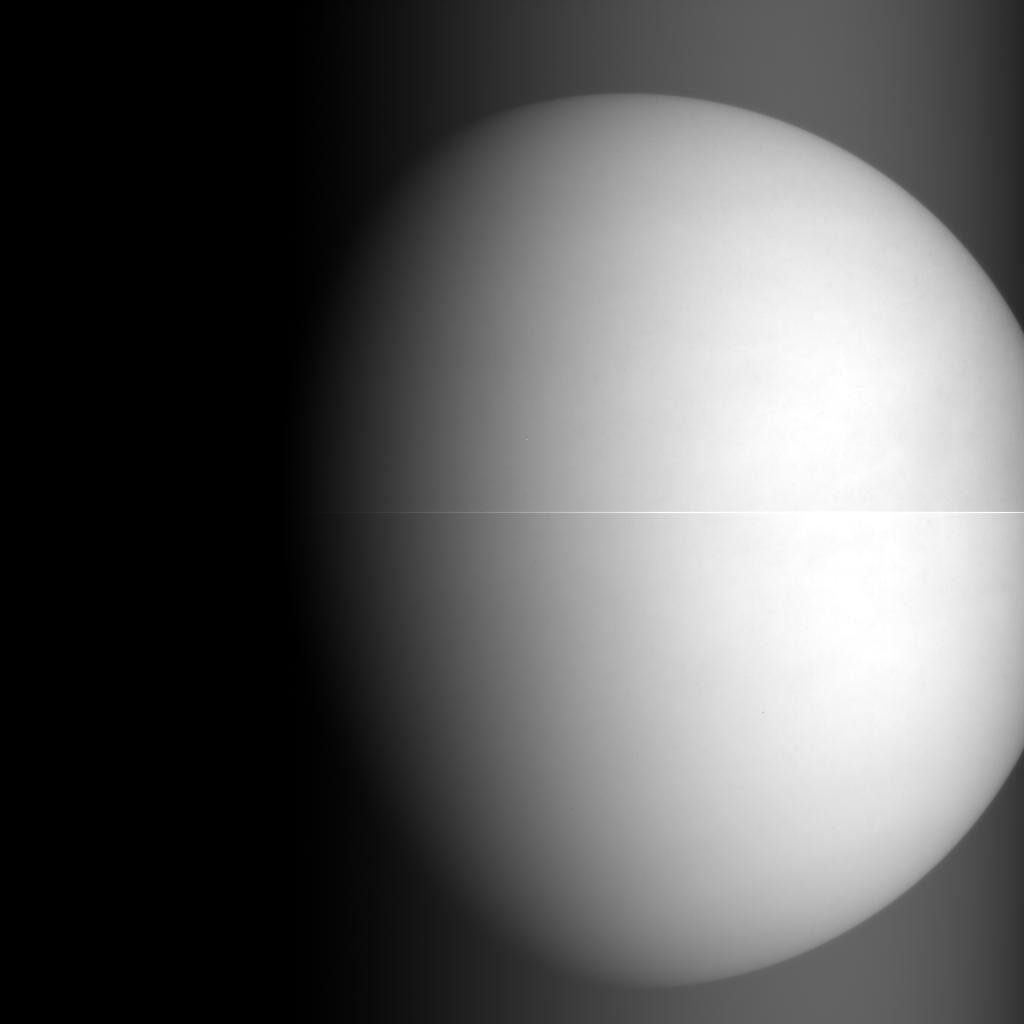

Controllers activated three of Akatsuki’s five cameras before the spacecraft arrived at Venus, and JAXA published the first views from the imagers Wednesday. The probe’s other two cameras are scheduled to be switched on in the coming weeks.

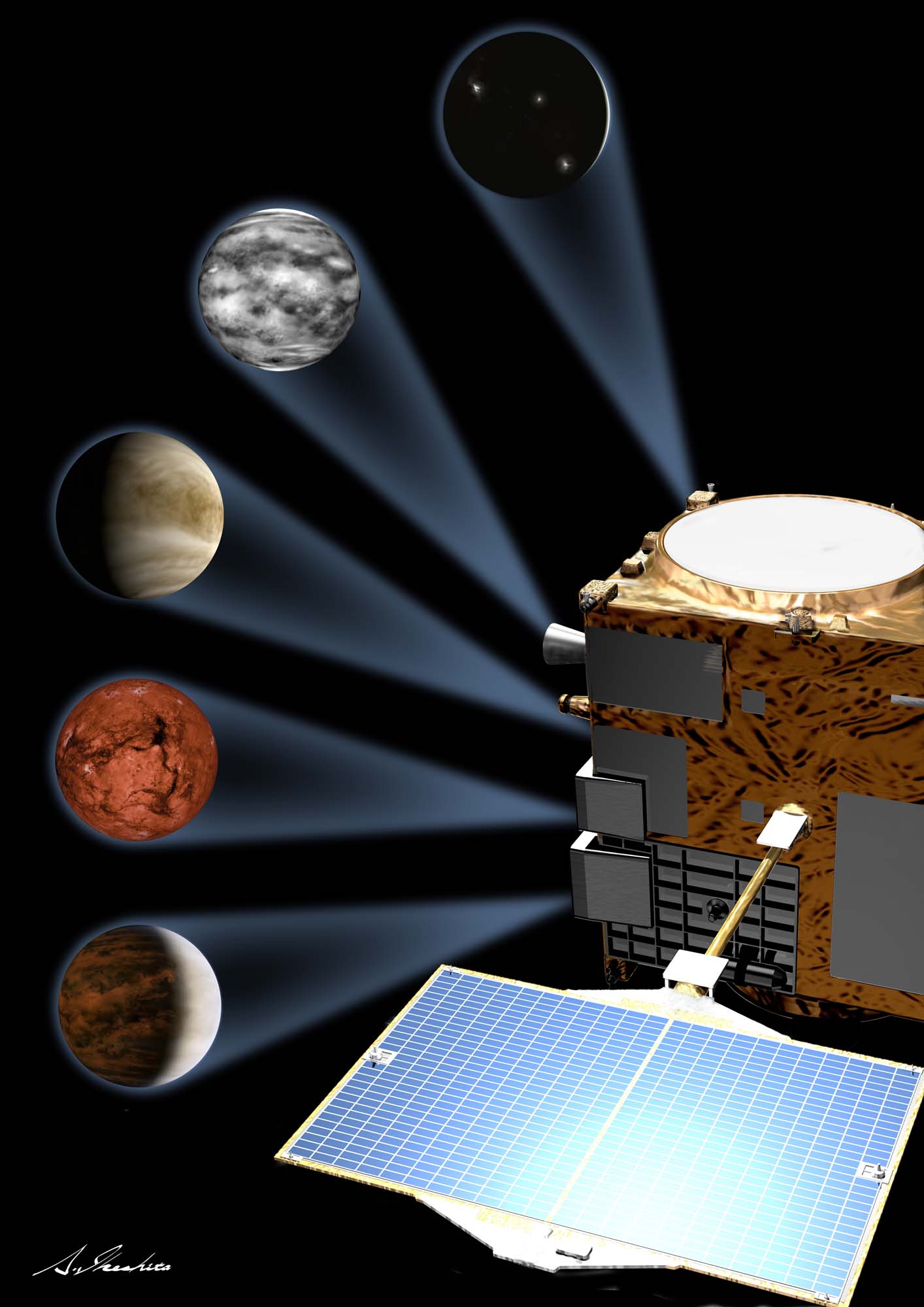

The camera suite on Akatsuki, which is also named the Venus Climate Orbiter, includes two imagers to see Venus in two infrared wavelengths, a longwave infrared camera, an ultraviolet sensor, and an instrument to resolve potential lightning strikes in the Venusian atmosphere.

Each camera is designed to study a different part of the super-thick, sweltering atmosphere surrounding Venus and blocking camera views of its surface.

“From far distances, we continually monitor the global-scale dynamics of the atmosphere and clouds, and of course, from close distances, we take close-up images of the atmosphere, the surface, and we also observe lightning and airglow when the spacecraft is in the shadow of Venus,” said Takeshi Imamura, Akatsuki’s project scientist at JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science.

The mission will observe climate and weather conditions on Venus, looking at cloud patterns just above the surface and the super-rotating cloud structures that dominate the upper atmosphere. The ultraviolet camera will also track sulfur dioxide, a precursor to cloud formation at Venus.

Scientists hope to see the surface of Venus with one of Akatsuki’s infrared cameras in a bid to find active volcanoes. The cocoon of clouds around Venus prevents visible cameras from ever seeing through to the ground.

The data stream from Akatsuki could also hold clues on how clouds form on Venus, with measurements of sulfur dioxide — a precursor to cloud formation — water vapor and carbon monoxide.

Researchers also plan to measure radio waves transmitted through the planet’s atmosphere to measure its profile.

Akatsuki’s orbit is much farther from Venus than if the probe had entered orbit on time in 2010. The spacecraft’s attitude control thrusters had enough power to steer Akatsuki into orbit, but only its main engine could take it closer to Venus.

Imamura said engineers have uploaded new software to Akatsuki to better see Venus from the spacecraft’s higher-than-planned orbit, reducing the data volume coming back to Earth to streamline the mission’s scientific return.

“By combining this information, we can model the three-dimensional structure of the atmosphere and the clouds,” Imamura said.

Akatsuki’s ultraviolet camera, one-micron infrared imager and longwave infrared instrument are ready for observations, JAXA said Wednesday. The two-micron infrared camera, lightning detector and a radio oscillator for Akatsuki’s atmospheric profile measurements will be checked and put into operation now that the spacecraft is in orbit.

The mission’s ground team will guide Akatsuki closer to Venus over the next few months, eventually putting the probe in a nine-day orbit around the planet.

Regular observations are due to begin in April 2016, officials said.

Before Akatsuki arrived at Venus, Imamura said engineers predicted the spacecraft had enough fuel for at least two years of operations, but that could be refined after a tally of leftover propellant following this week’s big burn.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.