European Space Agency flight controllers are plotting to send the Rosetta spacecraft on a controlled descent to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko next year to join the Philae landing probe, which made a bouncy touchdown on the comet’s craggy nucleus one year ago this week.

Rosetta begins an extended mission in December, with funding and fuel available to continue the spacecraft’s study of the comet through September 2016.

“We recently celebrated our first year at the comet and we are looking forward to the scientific discoveries the next year will bring,” said Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist, in a statement.

After a 10-year cruise through the inner solar system, Rosetta arrived in the vicinity of the comet in August 2014, and it dropped the Philae lander to comet 67P on Nov. 12, 2014. The comet’s orbit took it closest to the sun Aug. 13 — a point known as perihelion — as Rosetta backed off from the nucleus to avoid a potentially hazardous cloud of dust and gas growing around the comet.

Rosetta is now slowly moving back toward the comet as activity dies off as its distance from the sun grows. The spacecraft reached a point 170 kilometers, or 105 miles, from the nucleus Thursday, and Rosetta will go much closer in the coming months.

“Next year, we plan to do another far excursion, this time through the comet’s tail and out to 2,000 kilometers (about 1,200 miles),” Taylor said in a press release. “To complement that, we hope to make some very close flybys towards the end of the mission, as we prepare to put the orbiter down on the comet.”

The close flybys will give scientists a last shot at restoring a communications link with Philae, which mission control has not heard from since July.

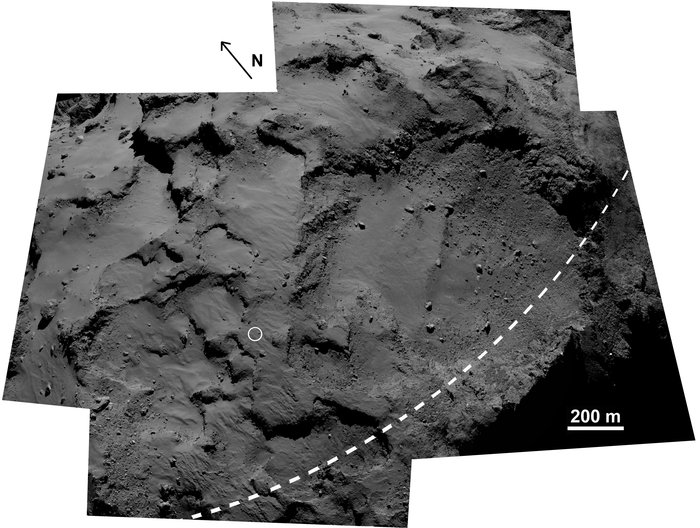

Philae’s anchoring harpoons and ice screws failed to discharge when it contacted the lander’s targeted touchdown site — a relatively flat sunlit area named Agilkia — and the probe rebounded, bounced and ended up up lodged against a cliff.

The wall of rock blocked sunlight from reaching Philae’s body-mounted solar arrays, and the lander drained its batteries two days later. Scientists say the lander still collected 80 percent of its planned science data during the abbreviated mission.

Engineers were optimistic the lander would awaken as the comet swept closer to the sun, warming the temperature inside Philae’s internal electronics bay and putting more sunlight on the solar panels. Philae’s team was vindicated in June, when the probe radioed home via its Rosetta mothership.

But Philae only made intermittent contact with the ground over the following month, and it went silent July 9.

Temperatures will likely be too cold for Philae in January, officials said.

Engineers placed Rosetta in hibernation on approach to comet 67P, but its current trajectory will take it even farther from the sun as the comet heads back into the cold depths of the outer solar system beyond Jupiter in its 6.5-year orbit.

Officials are inclined to conclude Rosetta’s mission next year due to three factors:

- Communications with Rosetta will be complicated in October 2016, when the comet and the Sun appear near the position in the sky as viewed from Earth, an event called solar conjunction.

- Rosetta will be low on fuel, leaving limited options for a secondary mission if the spacecraft can be put to sleep in a power-saving mode.

- The spacecraft was never designed to withstand a second hibernation, and there are questions whether Rosetta can survive a second sojourn through the cold outer solar system.

While details of the end-of-mission plan are yet to be finalized, ground controllers have begun thinking of how to delicately guide Rosetta to a “controlled impact” on the comet, officials said.

Managers at the European Space Operations Center in Germany have discussed the option to put Rosetta on the comet for months — officials talked about the idea with reporters after Philae’s landing a year ago — but the plan began to crystallize in recent weeks.

“We are still discussing exactly what the final end of mission scenario will involve,” said Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft operations manager at ESOC. “It is very complex and challenging, even more so even than the lander delivery trajectory our flight dynamics teams had to plan for delivering Philae.

“The schedule we’re looking at would first involve a move into highly elliptical orbits — perhaps as low as 1 kilometer (about 3,300 feet) — in August, before moving out to a more distant point for a final approach that will set Rosetta on a slow collision course with the comet at the end of September.”

Taylor compared Rosetta’s mission narrative to a soap opera, and he expects more drama in the craft’s final months. There is some hope Rosetta could operate on the comet’s surface after a soft impact, but such an outcome would require meticulous planning, and a bit of luck.

Lodiot said the chances of the spacecraft surviving the touchdown are remote.

“We’ll control Rosetta all the way down to the end, but once on the surface it will be highly improbable that we’ll be able to ‘speak’ to it anymore,” Lodiot said in an ESA statement.

With a finely-tuned high-gain antenna, which must be aimed at Earth to send and receive large volumes of data, and big solar panels stretching 32 meters (105 feet) tip-to-tip, Rosetta was never designed for such a maneuver. Many of the spacecraft’s appendages could be crushed during the landing attempt.

“Jokingly, around a bar, one might be able to say, ‘Oh, maybe we can try and tilt the solar arrays and get the antenna pointed in the right direction,'” Taylor said in an interview with Spaceflight Now earlier this year. “But that’s the thing of fantasy and comedic discussion at the moment. The key thing is depositing the orbiter on the comet and gaining those very, very close observations.”

The close-up encounters in the final throes of the mission will give Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera extraordinary views of the comet.

“We’ll get down six times as close as where we’ve been,” Taylor said. “That’s going to be pretty damn good. We’re talking centimetre resolution.”

Mark McCaughrean, a senior science advisor to ESA, said Rosetta’s own landing on the comet would be a “fitting end to an astronishing journey.”

“This story is not over. There’s just something about Rosetta,” Taylor says. “I wouldn’t want to say, ‘Yeah, we’re definitely going to try to steer the antenna and do all this,’ but one can imagine, just from the theatrics of this mission, this may be something we’d look into, because why not?”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.