With the flagship-class ExoMars program nearing the finish line after a decade in development, European Space Agency officials want to complete negotiations with the mission’s industrial teams before committing to a 2018 launch date for a European-built Mars rover.

Rolf de Groot, head of ESA’s robotic exploration coordination office, said the space agency is finalizing contracts with European industry to build a six-wheeled rover, a carrier stage for the trip from Earth to Mars, and critical components for a descent craft to be largely manufactured in Russia.

Liftoff of the ExoMars rover is set for May 2018, when the positions of Earth and Mars allow for the interplanetary journey. Launch opportunities to Mars generally come about every 26 months, and the next window opens in July and August 2020.

Engineers are under pressure to meet the 2018 launch window, and a formal schedule commitment will not come until ESA signs the final contracts for the mission.

“It’s pretty tight,” de Groot said. “At the moment, we don’t have a fully working schedule for 2018, but we are looking into possiblities to change procedures a bit and to tighten the schedule a little bit. We’re still confident we’ll be able to make it in 2018, but it’s a very tight schedule indeed.”

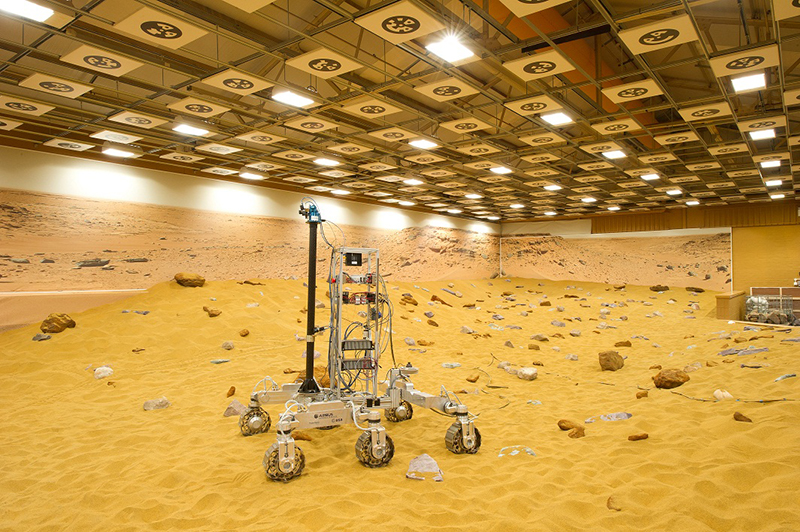

ESA’s prime contractor for ExoMars is Thales Alenia Space, which is completing work on a Mars orbiter and stationary lander set for launch next year. ESA assigned development of the 2018 rover to Airbus Defense and Space’s division in Britain, and OHB of Germany is working on the cruise stage.

“The negotiations on having the full schedule for 2018 are part of the industrial negotiations for the contract because they are the ones who have to make the schedule work,” de Groot said in a Sept. 25 interview. “It’s an ongoing effort to have a schedule for 2018, and we’re hoping at the end of this year to finalize the negotiations, which would also mean that by the end of the year, we hope to confirm a working 2018 schedule.”

Terms of the final contract could also update ESA’s cost estimate for the ExoMars program, which currently stands at 1.2 billion euros ($1.35 billion). That covers ESA’s costs for the 2016 and 2018 launches, not including contributions from ESA member states and international partners.

“Our estimated target cost (for both missions) is still 1.2 billion euros ($1.35 billion), but we still don’t have the final industrial proposal for the ’18 mission. It’s still an estimated cost, but this is the order of magnitude.”

The space agency has struggled to secure funds to meet the 1.2 billion euro cost projection. While the 2016 launch has been on secure financial footing for several years, the 2018 rover mission still faced a funding shortfall after a ministerial-level meeting of ESA member states in December 2014.

ESA partnered with Russia to keep the ExoMars mission on track for launches 2016 and 2018 after NASA pulled out of the project in 2012.

The ExoMars rover carries payloads to detect organic molecules — the building blocks of life — and a drill to collect subsurface samples.

Roscosmos — the Russian space agency — is providing two Proton rockets for the launches, a descent module to carry the ExoMars rover through the Martian atmosphere, sensors on the rover, and a water-sniffing detector and atmospheric chemistry instruments for the ExoMars 2016 orbiter.

The ExoMars 2016 mission consists of the Trace Gas Orbiter, a 4.1-ton (3,732-kilogram) spacecraft with sensors to map Mars landing sites and detect trace constituents in the Martian atmosphere like methane, which could indicate ongoing biological or geological activity.

A entry, descent and landing demonstrator named Schiaparelli will accompany the Trace Gas Orbiter to Mars, separating a few days before arrival for a touchdown in Meridiani Planum, a broad equatorial plain near the region being explored by NASA’s Opportunity rover.

The Trace Gas Orbiter’s prime science mission will last one Martian year — about two Earth years — and is expected to provide data relay services for the 2018 ExoMars rover and NASA’s Mars landers well into the 2020s from an orbit about 250 miles, or 400 kilometers, in altitude. NASA has provided Electra two-way radios for the ExoMars orbiter to relay telemetry and commands between Earth and assets on the Martian surface.

The orbiter/lander combo is set for launch March 14 after a joint ESA-Roscosmos steering board approved a two-month delay Sept. 24, de Groot said.

Technicians at Thales Alenia Space’s satellite factory in Cannes, France, are removing two pressure transducers from the Schiaparelli lander after their manufacturer — Moog Bradford of the Netherlands — notified managers of potential welding flaws that could cause a leak in the craft’s propulsion system.

The units monitored pressures in the propulsion system’s helium pressurant tank and hydrazine fuel tank, supplying housekeeping data deemed unessential to the operation of the lander’s rocket braking system, which will slow the craft’s final descent to the surface of Mars.

“We will not have the housekeeping data anymore, but this is not in the critical loop of the mission itself,” de Groot said. “We could have designed the mission even without them, but these things you normally put in there to have as much housekeeping data as possible to check whether all systems are functioning normally.”

Moog Bradford informed ExoMars officials the transducers came from a batch produced in 2013 that had cracks due to a faulty welding process, according to de Groot.

The possibility of a leak “was just too big a risk to take,” de Groot said.

“These cracks were not something we found in testing,” de Groot said. “It was something that was notified by the manufacturer of the transducers themselves. We do not have any proof that they will leak, but the risk is just too big that during the descent phase of the EDM (lander), that if these leaks did occur, they would immediately lead to the loss of the mission.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Rolf de Groot. Become a member today and support our coverage.

Unlike most Mars launch periods, 2016 has two distinct windows for ExoMars to reach Mars.

“It was already known some time ago that in 2016 we would have these two launch windows of three weeks,” de Groot said. “The trajectory is a little bit different, and the angle from which we will approach Mars is also a little bit different.”

Engineers may slightly adjust the Schiaparelli lander’s target ellipse in Meridiani Planum based on the adjusted trajectory.

“It’s a minor adjustment,” de Groot said. “The whole mission profile itself is, more or less, the same. We will arrive the same date (in October 2016), just at a slightly different angle. So for the rest, we don’t have to adapt the mission at all.”

One silver lining in the launch delay is ground teams can install the last orbiter instrument awaiting delivery — the mission’s Swiss-led high-resolution stereo mapping camera — while the spacecraft is still in Europe, de Groot said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.