Satellite shards scattered by the explosion of an aging U.S. military weather spacecraft in February will remain in orbit for many decades, according to researchers who specialize in space debris.

The Defense Meteorological Satellite Program Flight 13, or DMSP F13, spacecraft exploded Feb. 3 and produced up to 100 fragments large enough to be tracked by military radars on Earth.

The satellite was orbiting at an altitude of about 800 kilometers, or 500 miles, in a path that took the craft over Earth’s poles.

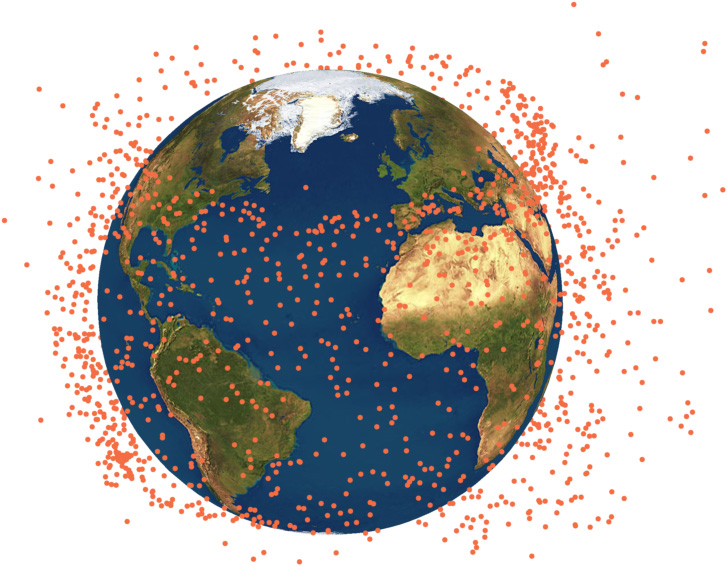

The energy from the explosion sent debris into orbits hundreds of miles above and below the satellite’s original path, according to a quarterly report issued by NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Experts said pieces of the satellite are well above the drag effects of the upper atmosphere.

“Unfortunately, this altitude regime is particularly cluttered with debris from a large number of historical breakups,” the report said. “The event occurred at a high enough altitude that much of the debris from this breakup will remain in orbit for many decades.”

Researchers at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom estimate the explosion generated more than 50,000 fragments larger than 1 millimeter — too small to be tracked by the ground-based radars.

Scientists from the university published a paper in the the Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics describing the expansion of the satellite’s debris cloud.

Satellite operators said in the weeks after the DMSP F13 explosion that the craft’s debris posed little risk to operational space missions. The European Space Agency said in March that its Earth observation satellites fly well below the concentration of debris from DMSP F13.

But updated data show the satellite chunks produced by the explosion are spread in a band around Earth, which can be crossed by spacecraft in very different orbits, according to Francesca Letizia, a PhD student at the University of Southampton who led research into the effects of the DMSP F13 explosion on other objects in space.

Letizia’s team used a new technique to model how the debris cloud changes with time, assessing the risk of a collision between a remnant piece of the satellite and another object in space.

“They produced a collision probability map showing a peak in the risk at altitudes just below the location of the DMSP F13 explosion,” the University of Southampton said in a May 6 press release. “The map was created by treating the debris cloud produced by the explosion as a fluid, whose density changes under the effect of atmospheric drag.”

“Treating the fragment band as a fluid allows us to analyze the motion of a large number of fragments very quickly, and much faster than conventional methods,” said Camilla Colombo, a lecturer in the University of Southampton’s Astronautics Research Group.

“In this way, the presence of small fragments can be easily taken into account to obtain a refined estimation of the collision probability due to an explosion or a collision in space,” Colombo said in a press release.

The top ten spacecraft most at risk from fragments of DMSP F13 are mainly U.S. and Russian satellites in polar orbits, researchers said.

“Even though many of these objects will be no bigger than the ball in a ballpoint pen, they can disable a spacecraft in a collision because of their enormous speed,” said Hugh Lewis, a University of Southampton scientist and a UK Space Agency representative to the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee. “In the case of the DMSP F13 explosion, our work has shown that the introduction of a new cloud of small-sized debris into orbit will have increased the risks for other spacecraft in the vicinity, even if the risk from the larger fragments has been discounted.”

The most likely culprit for the DMSP F13 failure was an explosion of one of the satellite’s nickel-cadmium batteries, according to NASA’s orbital debris report. The Air Force said ground controllers noticed a sudden temperature spike in the satellite’s power system before it spun out of control Feb. 3.

International guidelines call for decommissioned satellites and spent rocket bodies to be “passivated” when their missions are complete, a process that includes disconnecting internal batteries from the spacecraft’s circuitry and venting leftover fuel and high-pressure gases.

Built by Lockheed Martin and launched in 1995, DMSP 13 had not yet been safed because it was still operational when it broke apart in early February.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.