Wednesday marked one year until the launch of a NASA seismic station to Mars, and scientists believe they have found a suitable operating post for the lander as engineers race to keep the mission on schedule for liftoff in a narrow 26-day window next March.

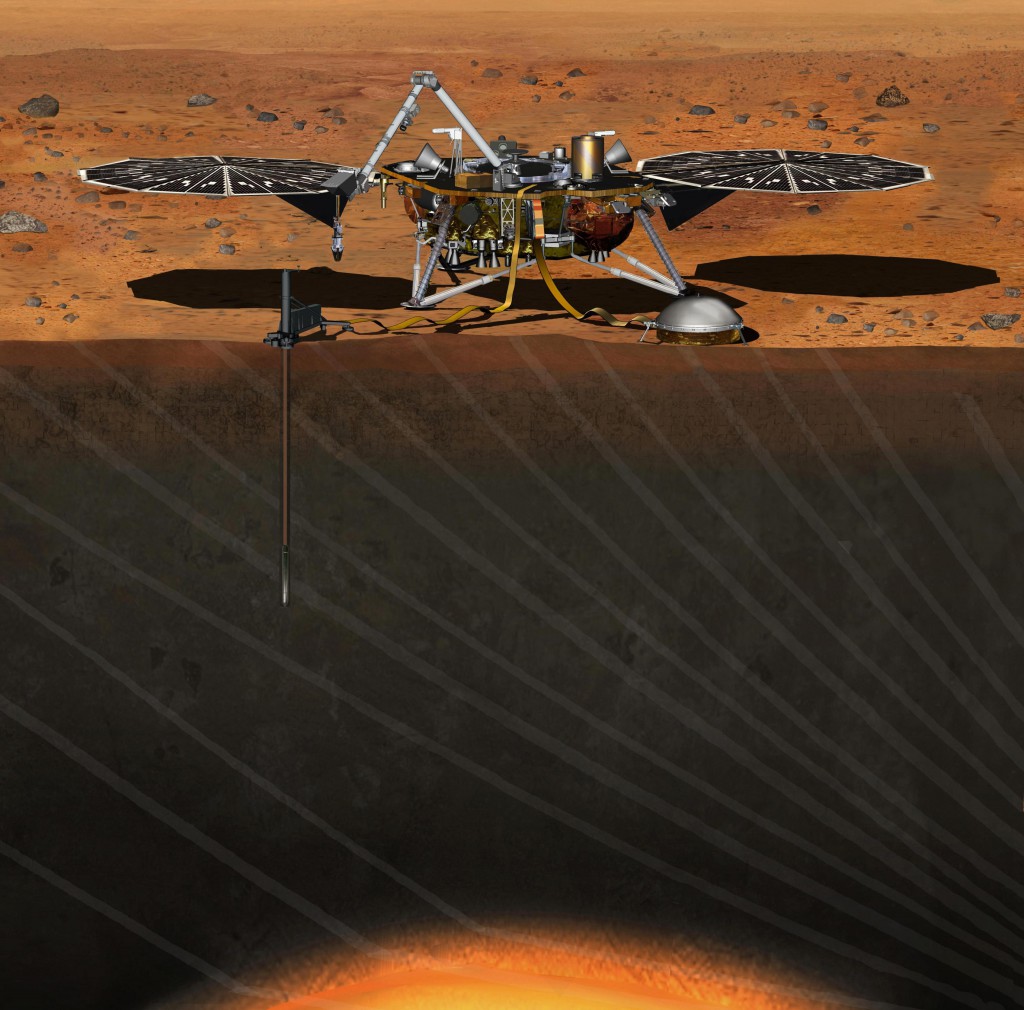

The lander will land on Mars and deploy instruments to detect “marsquakes” and hammer up to 15 feet into the soil to take the red planet’s temperature. The data will be crucial for scientists to study the deep Martian interior and learn how rocky planets like Mars, Earth, Venus and Mercury formed.

Named InSight — short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — the mission has only a few weeks to depart from Earth next year and reach Mars. Opportunities to launch to Mars come every 26 months or so, when the planets are in the right positions to make the trip feasible.

InSight’s liftoff from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California is targeted for around 1:50 a.m. PST (4:50 a.m. EST; 0950 GMT) on March 4, 2016, according to Bruce Banerdt, the mission’s lead scientist from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The lander will take off aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, marking the first Mars mission to launch from the West Coast spaceport. NASA’s previous Mars-bound spacecraft have launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The three-legged lander will arrive at Mars on Sept. 28, 2016, streak through the Martian atmosphere inside a protective heat shield, deploy parachutes and brake to a soft touchdown with the help of rocket thrusters.

InSight is under construction at a Lockheed Martin facility near Denver, where it will be shaken, heated and blasted with radiation later this year to verify the spacecraft will survive the trials of flying to Mars.

But there is a schedule crunch.

“We’ve got a lot of critical systems that are running late,” Banerdt said. “We’ve seen a lot of progress, but not as much progress as we’d hoped.”

He the problems have not affected InSight’s budget so far. InSight’s cost is estimated at $542 million, according to a NASA budget document released in February.

“We have margin on paper, but everybody thinks that this is very tight,” he said in a Feb. 25 meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group, a panel of scientists chartered by NASA to help plan future scientific research at the red planet.

“There was a time last fall where we were not at all sure we were going to be able to make launch due to a lot of delays and a lot of technical problems, largely in the payload,” Banerdt said.

The InSight landing platform is a near-copy of NASA’s Phoenix lander, which touched down on Mars’ northern polar plains in 2008 and worked for five months before sunlight waned, robbing the craft of its power source. Phoenix confirmed the presence of water ice just below the Martian surface near the north pole.

The most serious problems on InSight are with the spacecraft’s avionics system and a seismometer instrument named SEIS being developed by CNES, the French space agency, Banerdt wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now.

“So far, we have maintained pretty good schedule margin by rearranging tasks in the (assembly, test and launch operations) flow,” Banerdt wrote. “We still have more than 50 days of schedule margin, with several things pretty close to the critical path. I would say right now the spacecraft avionics and the SEIS instrument are probably the pacing items.”

He said InSight’s basic structure and propulsion system are finished, along with the probe’s landing radar, communications system, batteries, and the solar arrays that will power the spacecraft on the cruise from Earth to Mars. Some of the spacecraft’s electronics are also complete, but the flight computer and power control system are behind schedule.

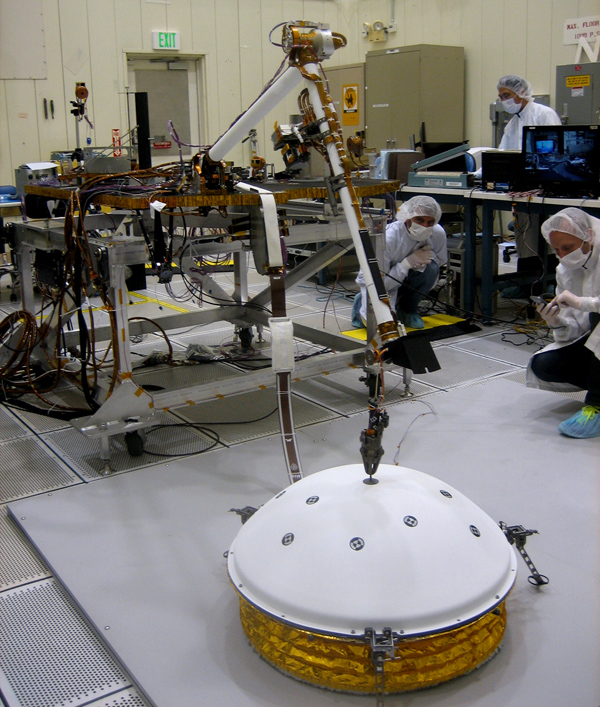

InSight will place its two primary instruments on the Martian surface with a robotic arm developed by JPL. Motors inside the arm’s joints failed in testing, and engineers found the motors were coated in too much epoxy.

Reworked motors for the robotic arm will fix the problem, but the glitch delayed the arm’s delivery by about six months until June, Banerdt said.

The seismometer, one of the two scientific centerpieces of InSight’s mission, also failed a critical test last year.

“We delivered the flight unit last summer in July, we put them on the test stand, and they didn’t work,” Banerdt said. “They’re supposed to measure vibrations, and they were stuck. We spent many months figuring out what the problems were with that.”

The seismometer is based on a design that flew on Russia’s Mars 96 mission, which never made it to the red planet due to a mishap during launch.

“”We thought we had a pretty mature design, and we did for something that was about an order of magnitude less sensitive. In fact, the French had actually flown that seismometer. We upped the game to that 10–9 m/s2 (sensitivity), and we found a lot of issues that were not expected.”

The problems are solved now, after a joint engineering team from CNES, JPL and the Paris Institute for Earth Physics diagnosed the issue and restarted assembly of the seismometer’s components, which include tiny pendulums that swing when hit by a seismic wave.

InSight also carries a German instrument that will burrow underground to measure the heat flow coming from the Martian interior. The hammering drill had to be redesigned to avoid damaging itself as it pierced into red planet’s crust.

The mission also carries a Martian weather station, and scientists will analyze radio signals passed between InSight and Earth to measure the wobble in the planet’s rotation, a data point that could help determine whether Mars has a solid or molten core.

Once InSight touches down on Mars, it will open its fan-like solar panels, then mission planners have set aside up to two months for the robot arm to grab the seismometer and subsurface heat probe from the lander’s deck and lay them next to the spacecraft.

The mission is scheduled to last one Martian year after landing, or nearly two Earth years.

InSight is heading for a flat landing site near the Martian equator in a region named Elysium Planitia. The broad equatorial plain was selected because it is free of large craters and boulders, giving the lander a good shot at touching down safely, then having a smooth place to place its instruments.

Matt Golombek, a JPL scientist who leads the panel selecting InSight’s destination on Mars, joked the Elysium Planitia site is “among the most boring places on the planet.”

Officials have selected one section of the region as the most likely target for InSight, which will target an ellipse stretching 81 miles east-to-west and 17 miles north-to-south, according to a NASA press release.

NASA plans to formally pick InSight’s target later this year, but the ellipse centered at four degrees north latitude and 136 degrees east longitude is the prime candidate.

Golombek said a high-resolution scan of InSight’s probable target ellipse revealed just one rock that could pose a problem if the lander got unlucky and came down on it. Stereo imagery from NASA’s orbiters will continue taking pictures of the area over the next few months, collecting imagery that will feed into NASA’s final decision.

There is one drawback.

Elysium Planitia lies near the same longitude as the Curiosity rover in Gale crater, and the north-south tracks of NASA’s communications relay orbiters mean they will pass over Curiosity and InSight at almost the same time.

“It’s in the most inconvenient place on the planet,” Golombek said. “It’s inconvenient because it’s due north of the Curiosity landing site, and thus every communications pass that goes between Curiosity and us is either going to have to be shared or something else.”

But the benefits outweigh the costs.

The leading landing ellipse in Elysium Planitia is “among the smoothest, least rocky and safest places on Mars” for a mission to go, Golombek said.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.