STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS “SPACE PLACE” & USED WITH PERMISSION

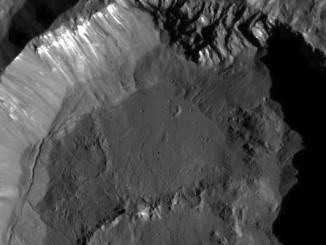

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft is closing in on the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest body in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, beaming back increasingly sharp pictures revealing a heavily cratered world with unexpected — and so far, mystifying — spots of light that may be reflections off exposed ice or some other material.

Whatever they are, the surprising spots have generated widespread interest among scientists and non scientists alike as Dawn completes its rendezvous and slips into orbit around Ceres early Friday, three years and more than 900 million miles after wrapping up a year-long study of the rocky asteroid Vesta.

“Suffice it to say, these spots were extremely surprising to the team, and they have been puzzling to everybody who’s seen them,” Carol Raymond, Dawn deputy principal investigator, told reporters Monday. “The team is really, really exited about this feature because it is unique in the solar system.”

A movie made up of recent Dawn images shows Ceres rotating through a complete 9.1-hour “day.” The bright spots stop shining when they rotate into darkness, indicating they are, in fact, reflected sunlight, possibly from exposed ice or salt deposits.

The presumed deposits may have been uncovered by a recent impact or possibly the result of some much less probable mechanism like ultra-low temperature “cryovolcanism.” But for now, no one knows. And given their unusual brightness, interest is high.

“We will be revealing its true nature as we get closer and closer to the surface,” Raymond said. “So the mystery will be solved, but it is one that’s got us on the edge of our seats.”

And one that will require a bit more patience. Dawn is approaching Ceres from its dark side and it will take several more weeks to get into a position to study the bright spots in more detail as the spacecraft spirals inward, eventually reaching a 235-mile-high mapping orbit in December.

The $473 million project is “one of the coolest missions to one of the last unexplored worlds in the solar system,” said Robert Mase, the Dawn project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

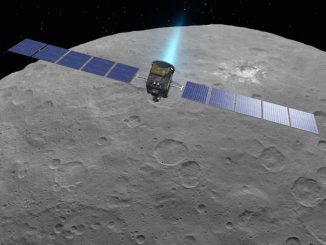

Dawn is the first spacecraft to orbit more than one body, the first to visit a dwarf planet — Ceres — and the first operational science probe to rely on ion propulsion, using solar-generated electricity to accelerate xenon ions to enormous velocities, producing a gentle but almost continuous thrust.

“We go from zero to 60 in about four days,” Mase said. “However, ion engines are about 10 times more efficient than conventional chemical systems, and we can continue to thrust and accelerate for days and weeks and months or, as Dawn has now for more than five years, to generate tremendous velocities.”

Ceres was discovered in 1801 by the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi. It was the first asteroid ever discovered and it is the largest in the asteroid belt, a roughly spherical body measuring 606 by 565 miles.

“One of the first things you notice is how round Ceres is,” Raymond said. “And Ceres’ roundness is one of its planetary characteristics. We also know that Ceres is much lighter than the rocky planets and so we know it retained a lot of water and light volatile elements that were present in the solar nebula when Ceres was formed.

In contrast, bodies like the moon and Vesta suffered melting from major impacts that caused the water and other light elements to boil away, “leaving them dry and rocky,” Raymond said.

“One of the prime motivations of the Dawn mission is to examine these building blocks of the planets, Vesta and Ceres, which are two intact proto-planets from the very dawn of the solar system,” she said. “They’re literally fossils that we can investigate to really understand the processes that were going on at that time.”

The initial views of Ceres have revealed remarkably smooth areas, chaotic fracture zones and craters of all sizes, she said. The terrain likely holds clues about the dwarf planet’s internal structure and whether a layer of ice exists that might be a remnant of a now frozen sub-surface ocean.

“We know that Ceres retained a lot of volatiles and its shape is consistent with a differentiation into a rocky core and an ice mantle,” Raymond said. Given heating from radioactive compounds, “it’s inevitable that that ice would have existed as an ocean at some time in the past.

“So, we do expect that in the past there was ocean in contact with the rock beneath an ice cap and that at present it’s an ice layer that’s beneath a crust of infalls and dust and clays and deposits from sublimation.”

Last year, a European spacecraft studying Ceres from afar detect traces of water vapor in specific longitudinal zones. Raymond said the bright spots are in one of those zones “so it might be related to that water vapor emission.”

“It’s association with the impact crater may indicate that impact heating resulted in exposure of underlying ice, it’s vaporization, and perhaps we’re seeing a deposit that was left behind, which is rich in material like salts,” she said.

Dawn is equipped with redundant multi-filter cameras sensitive to visible and near infrared light, a gamma ray and neutron detector that can characterize the elemental makeup of the upper few feet of the crust and a visible and infrared mapping spectrometer to study the mineralogy of the dwarf planet.

If all goes well, Dawn will reach its science mapping orbit in December and complete its primary mission in June 2016. A few months later, supplies of hydrazine maneuvering fuel, used to aim the spacecraft and its instruments at Ceres and to reorient the probe to transmit data back to Earth, are expected to run out and Dawn’s mission will come to an end.

“Dawn will get down to its lowest orbit, and the plan is for the spacecraft to stay there indefinitely,” Mase said. “That’s where the mission would end. The orbit is designed such that it’s stable for a very long period of time, so Dawn will actually stay in that orbit for …hundreds of years.”