SpaceX will test out new stabilizing fins that could help land the first stage of its Falcon 9 rocket on a floating barge in the Atlantic Ocean after liftoff on a space station resupply mission in mid-December, according to Elon Musk, the company’s billionaire leader.

Hoping to use an operational flight as an experiment to advance the company’s bid for a reusable rocket — a breakthrough that could change the landscape of the launch industry if perfected — SpaceX is finishing work on a ocean-going landing pad at a Louisiana shipyard.

The vessel could be used to wring out how to program rocket boosters to fly themselves back to the ground from the edge of space more than 50 miles up.

Musk posted a brief description of the barge, along with four “grid fins” to aerodynamically stabilize the rocket’s first stage during descent, to his Twitter page Saturday.

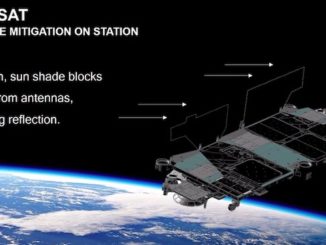

Dubbing the vessel an “autonomous spaceport drone ship,” Musk wrote the landing pad uses thrusters repurposed from a deep sea oil drilling rig to keep the barge within 3 meters — about 10 feet — of the correct position.

Emblazoned with a SpaceX logo in the center of a bull’s-eye painted on a black deck, the barge is 300 feet long with extendable wings to stretch its width to 170 feet, according to Musk.

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/536262624653365248

SpaceX’s next launch is set for Dec. 16 from Cape Canaveral with an unmanned Dragon cargo ship carrying more than 3,700 pounds of supplies and experiments for the International Space Station.

The launch will mark SpaceX’s fifth operational logistics mission to the complex under contract to NASA. The company’s current agreement is worth $1.6 billion and covers 12 cargo flights through the end of 2016.

The Falcon 9 rocket set to launch Dec. 16 is outfitted with aerodynamic fins stowed against the launcher during the first stage’s nearly three-minute firing after liftoff.

After releasing the rocket’s upper stage to propel the Dragon supply ship into orbit, the lower part of the booster will fire a subset of its nine engines for a re-entry burn to guide it toward a designated landing zone in the Atlantic Ocean northeast of Cape Canaveral.

The rocket will deploy the four grid fins in an “X-wing” configuration during re-entry, Musk tweeted. He said each fin has the ability to be independently actuated for pitch, yaw and roll control, and engineers added the stabilizers after initially trying to control the descent with cold gas nitrogen thrusters.

Testing operation of hypersonic grid fins (x-wing config) going on next flight pic.twitter.com/O1tMSIXxsT

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) November 22, 2014

The rocket deploys four landing legs just before reaching the landing point.

SpaceX achieved two controlled splashdowns of the Falcon 9 rocket’s 14-story-tall first stage earlier this year. On both flights, the rocket fell over and broke apart after the booster slid vertically into the Atlantic Ocean.

While the accomplishments showed progress in SpaceX’s effort to recover its rockets for reuse, the company wants to return a first stage intact for inspections and refurbishment.

“What we need to do is be able to either land on a floating platform, or ideally boost back to the launch site and land back at the launch site,” Musk said in remarks at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology last month. “But before we boost back to the launch site and try to land there, we need to show that we can land with precision over and over again. Otherwise, something bad could happen if it doesn’t boost back to where we intended.”

Musk assessed the probability of landing the rocket on the floating platform on the first try as “probably not more than a 50 percent chance.”

The video below shows a test flight of SpaceX’s Falcon 9R rocket — a vertical takeoff and landing testbed — with aerodynamic fins. Musk says the fins on the Falcon 9 launch in December are larger.

“The leg span of the rocket is 60 feet, and this (ship) is going to be positioning itself out in the ocean with engines that will try to keep it in a particular position,” Musk said. “But it’s tricky. You’ve got to deal with these big rollers and GPS errors. It’s not anchored because it’s out in the Atlantic.”

If SpaceX succeeds in recovering the rocket, Musk told the audience at MIT he believes engineers can fly the first stage again.

“There are at least a dozen launches that will occur over the next 12 months, and I think it’s quite likely — probably 80 to 90 percent likely — that one of those flights we’ll be able to land and refly. So I think we’re quite close.”

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.