A new-generation weather satellite launched in November promising to deliver better images of hurricanes, storms and clouds than any mission before has returned its first tantalizing pictures from geostationary orbit.

NOAA released the first images from the GOES-16 weather satellite Monday in conjunction with the start of the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society in Seattle.

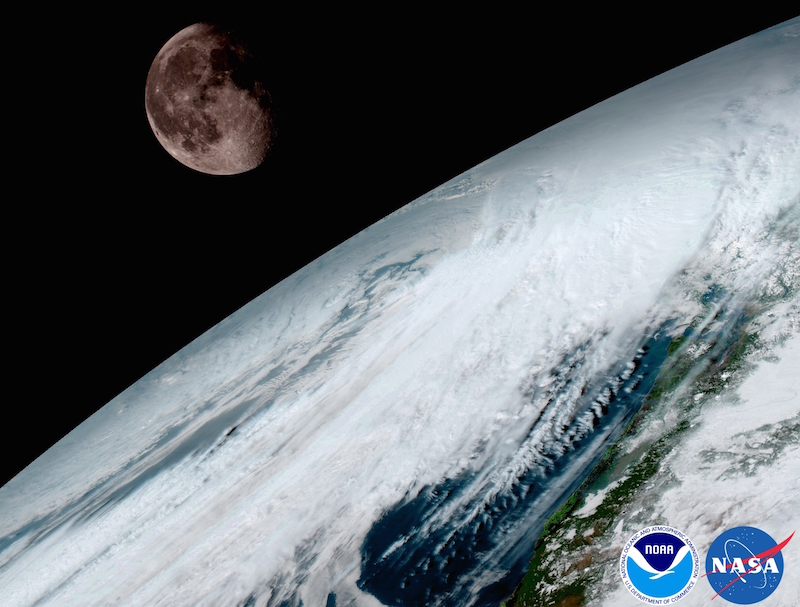

“Seeing these first images from GOES-16 is a foundational moment for the team of scientists and engineers who worked to bring the satellite to launch and are now poised to explore new weather forecasting possibilities with this data and imagery,” said Stephen Volz, NOAA’s assistant administrator for satellite and information services. “The incredibly sharp images are everything we hoped for based on our tests before launch. We look forward to exploiting these new images, along with our partners in the meteorology community, to make the most of this fantastic new satellite.”

The GOES-16 satellite, previously known as GOES-R, launched Nov. 19 from Cape Canaveral on-board a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The observatory is the first satellite in a series of at least four upgraded weather sentinels to be launched into geostationary orbit nearly 22,300 miles (35,800 kilometers) over the equator. At that altitude, the satellites move at the same speed of Earth’s rotation, allowing them to continuously watch over the same part of the planet.

The four-satellite program is costing the U.S. government about $11 billion, a figure that includes the construction of the spacecraft and their advanced instruments, launchers, and modernized ground systems.

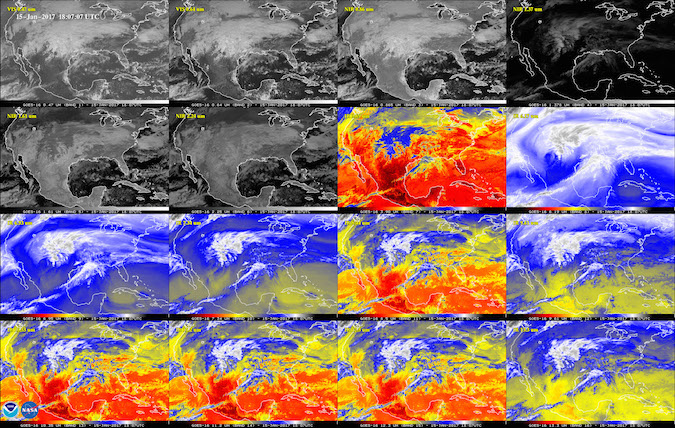

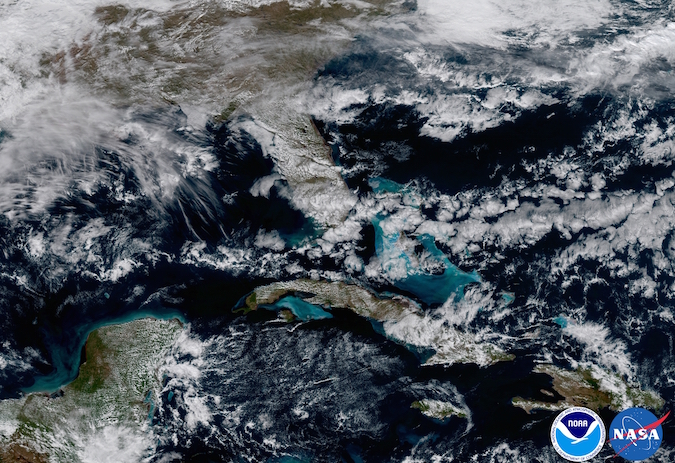

The centerpiece of the new satellites is the Advanced Baseline Imager, a camera that can see in 16 different wavelengths to determine cloud type, distinguish between clouds, fog and volcanic ash, and track moisture movements inside clouds. Previous GOES-class satellite cameras could only see in five channels.

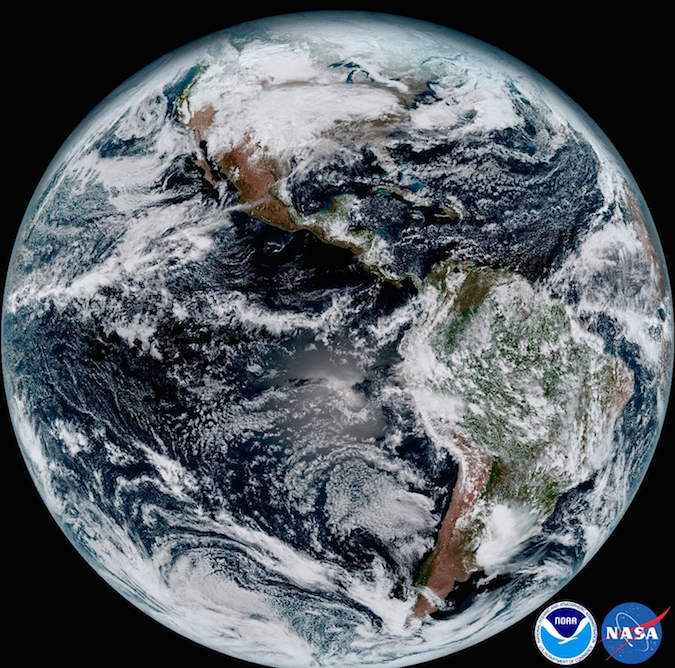

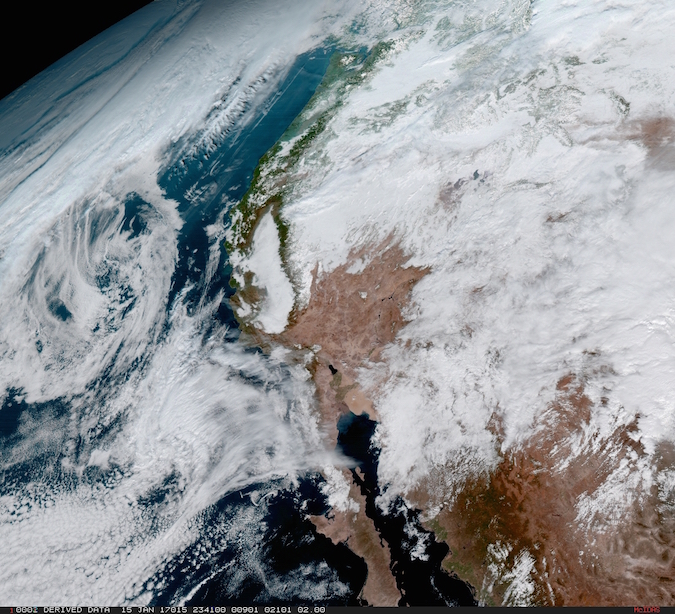

A full-disk image of Earth captured by GOES-16’s imaging camera Jan. 15 was among the pictures released by NOAA on Monday, showing a swath of the planet from Guam, across the Americas, to West Africa.

Manufactured by Lockheed Martin, GOES-16 is currently in a test location in geostationary orbit, and NOAA officials will announce in May whether the spacecraft will begin service over the Pacific or the Atlantic.

NOAA operates two active GOES weather satellites over the equator at 135 degrees and 75 degrees west longitude — the so-called GOES-West and GOES-East positions — to provide coverage from the Western Pacific to the West Coast of Africa.

That allows forecasters to track typhoons in the Pacific and storm fronts approaching the U.S. West Coast, while simultaneously observing developing tropical cyclones emerging off Africa.

NOAA said GOES-16, which is still undergoing post-launch checkouts, should be fully operational by November 2017.

Once officials decide if GOES-16 will head to the GOES-West or GOES-East positions, NOAA will deploy the follow-on GOES-S observatory to the other location when it launches in early 2018.

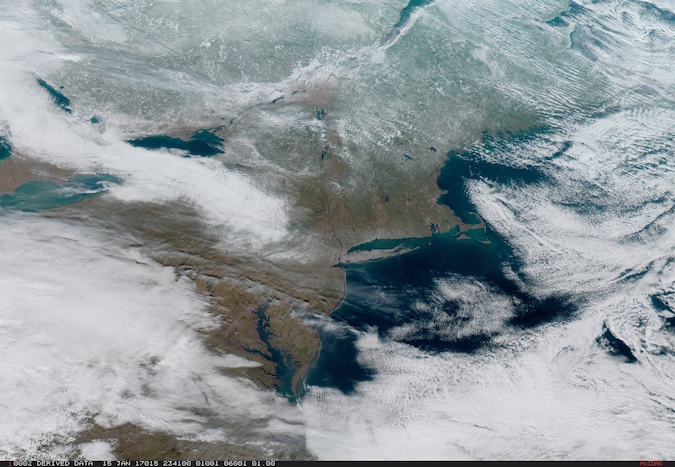

“This image is much more than a pretty picture, it is the future of weather observations and forecasting,” said Louis Uccellini, director of NOAA’s National Weather Service. “High resolution imagery from GOES-16 will provide sharper and more detailed views of hazardous weather systems and reveal features that previous instruments might have missed, and the rapid-refresh of these images will allow us to monitor and predict the evolution of these systems more accurately. As a result, forecasters can issue more accurate, timely, and reliable watches and warnings, and provide better information to emergency managers and other decision makers.”

Along with the Advanced Baseline Imager, the new series of GOES weather satellites host lightning detectors and sensors to monitor solar activity and space weather.

Each ABI, built in Fort Wayne, Indiana, by Harris Corp., works by moving two mirrors to scan in the north-south and east-west directions, allowing the camera’s sensors to build up images of the full disk of Earth, or target specific locations where severe weather merits a closer look.

The imager aboard GOES-16 is similar to upgraded cameras, also built by Harris Corp., that debuted on two Japanese weather satellites launched in 2014 and 2016. The ABI on the NOAA’s new observatory is the first such instrument positioned over the United States.

With the ABI cameras, the north-south mirror’s field-of-view is 60 times bigger than possible with the imager on NOAA’s current GOES satellites, according to Paul Griffith, chief engineer for the ABI instruments at Harris.

“It takes about 1,370 scans to collect the full disk right now, and ABI can do it in 22 scans,” Griffith said in an interview with Spaceflight Now before the launch of GOES-16.

“Because it takes far fewer scans, we can not only collect the image faster, but we can scan slower,” Griffith said. “Each scan is actually much slower than with the current imager, yet we can still do more rapid collection. Scanning slower means we can collect more light, which means we can deliver the finer resolution with the same radiometric accuracy.”

The instruments can also simultaneously capture wide-angle views of the entire disk of Earth while scanning across localized regions.

Clouds swirl in the sky over Florida in this animation from #GOES16! See more images from this next-gen spacecraft @ https://t.co/MDdSUau4JZ pic.twitter.com/bShGHpJk2n

— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) January 23, 2017

In the case of NOAA’s GOES satellites, that means shots zoomed in on the continental United States, hurricanes churning in the Atlantic Ocean, and tornado outbreaks in the Great Plains. The Himawari satellites can take quick-look imagery of the Japanese islands or typhoons approaching from the Pacific.

For comparison, NOAA’s current GOES satellites can take a full disk image — covering a region from Africa to the Pacific, and from the Arctic to Antarctica — about once every half-hour. The ABI-equipped GOES-R series can take the same type of image — with higher resolution and in more wavelengths — at least once every 15 minutes, and images spanning the continental United States every five minutes.

The GOES-R series will return pictures of hotspots like hurricanes at a cadence of once every 30 seconds, an improvement from the five-minute rapid scans available today.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.