In the week since it departed the International Space Station to wrap up a successful cargo delivery mission, Orbital ATK’s Cygnus supply ship hosted a combustion research experiment, deployed four small satellites for a San Francisco-based startup, then descended into Earth’s atmosphere Sunday for a destructive re-entry.

Sunday’s descent was the Cygnus freighter’s final act, destroying the spacecraft and its contents as intended as the spaceship streaked over the remote South Pacific Ocean, disposing of waste and other items discarded by the space station’s crew.

Debris from the re-entry, which occurred around 6:40 p.m. EST (2340 GMT) Sunday, fell in the sea east of New Zealand, according to Orbital ATK, owner and operator of the Cygnus spacecraft.

Orbital ATK launched the supply ship Oct. 17 aboard an Antares rocket from Wallops Island, Virginia. The successful liftoff was the first flight of Orbital ATK’s upgraded Antares rocket with new engines, a design change instituted in the wake of a launch failure in 2014.

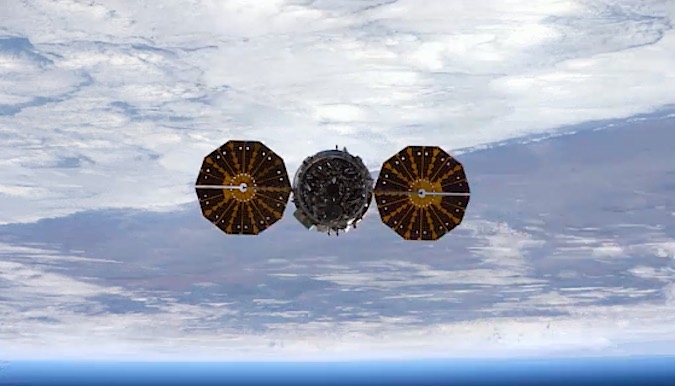

The 21-foot-long (6.4-meter) cargo carrier, dubbed the S.S. Alan Poindexter after the late astronaut, arrived at the space station Oct. 23 with approximately 5,163 pounds (2,342 kilograms) of experiments and provisions for the research lab’s crew.

Astronauts unpacked the supplies and replaced them with trash before the Cygnus spacecraft departed the complex Nov. 21 with 2,469 pounds (1,120 kilograms) of items tagged for disposal.

Once Cygnus was released from the space station’s robotic arm last week, the spacecraft’s next task was to conduct a NASA-sponsored flammability experiment aimed at improving safety for future crews heading into deep space.

Nine samples inside a flame-proof container aboard the Cygnus spaceship ignited later Nov. 21 for scientists to learn how flames grow and are fueled in microgravity.

“One of the least understood risks in space is how fire propagates (and) starts,” said Jitendra Joshi, technology integration lead for NASA’s advanced exploration systems division, before the mission’s launch. “How do you control the fire? How do you detect the fire? All these things. You can’t call 911 like on Earth to come help you.”

The coupons were held inside the Saffire 2 experiment’s enclosure measuring 3 feet by 3 feet by 5 feet (0.9 meters by 0.9 meters by 1.5 meters), and cameras inside the container collected imagery of each sample burning. The data was downloaded to the ground once the experiment was completed.

Video of the burning of one of the Saffire 2 samples is posted below.

Some of the samples on Saffire 2 — or Spacecraft Fire Experiment 2 — measured as large as 2 inches by 10 inches (5 centimeters by 25 centimeters), and scientists planned to use the specimens to assess the response of each material and oxygen flammability limits, according to NASA.

The materials included four samples of silicon at different thicknesses and a piece of Nomex, a commercial fire retardant. There were also specimens of cotton-fiber and plexiglass, a common material used in spacecraft windows.

Scientists reported the experiment worked as expected, and they received all the imagery they expected.

The Saffire 2 experiment followed a similar investigation hosted on the previous Cygnus cargo mission after it left the space station in June. A third Saffire experiment is planned on the next Cygnus flight set for launch in March, and Joshi said scientists are working on more Saffire payloads that could fly in the coming years.

Joshi said the results of the Saffire experiments, developed by a team based at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Ohio, will help engineers select safer materials for use inside future piloted spacecraft.

After the conclusion of the Saffire 2 experiment, ground controllers sent commands for the cargo craft to head to a higher orbit stretching as high as 300 miles (500 kilometers) to set up for the deployment of four small satellites Friday.

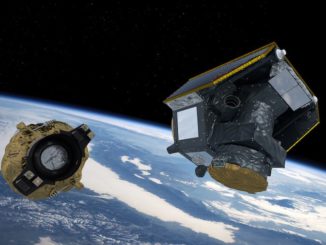

Four Lemur 2 CubeSats for Spire Global, a commercial satellite operator based in San Francisco, sprung out of their deployers outside the Cygnus spacecraft as planned.

Spire arranged for the high-altitude drop-off — a first for a space station cargo mission — with Orbital ATK and NanoRacks, the Houston-based company that provided the CubeSat deployer mechanism.

The partnership “leveraged the performance of the Cygnus spacecraft itself as well as NanoRacks’ proven deployment capability,” said Jenny Barna, Spire’s launch manager and a former propulsion engineer at Orbital ATK. “It’s truly an innovative mission profile and we’re honored to ride with Cygnus to space. The effort that NanoRacks, Orbital and NASA have put forth to make this a reality is a testament to the brilliance of public-private partnerships.”

NanoRacks has a separate CubeSat deployer on the space station itself that has sent more than 100 of the small spacecraft into orbit. But CubeSats do not carry propulsion systems to maintain or raise their orbits, so aerodynamic drag at the space station’s altitude of more than 250 miles (400 kilometers) forces their re-entry within months.

Spire officials said the higher orbit in which their satellites were released will give the platforms, each about the size of a shoebox with extendable antennas, about two years of life, compared to nine months at the space station’s altitude.

Shifting the CubeSat deployments off the space station also frees up time for astronauts, who must prepare the spacecraft for release through the Kibo module’s airlock.

The Lemur 2 satellites carry GPS radio occultation antennas, using satellite navigation signals passed through Earth’s atmosphere to derive temperature and humidity profiles that can be fed into numerical forecast models.

Spire’s satellites also track ships out of range of terrestrial receivers.

With the latest four satellites added to its fleet, Spire said it now has 16 operational craft in orbit providing data for the company’s maritime and weather data clients. The company has launched a total of 21 CubeSats, some of which have ended their missions, including one that because stranded inside its NanoRacks deployer on a previous Cygnus spacecraft in June.

Spire won a $370,000 contract from NOAA in September to supply pilot data for the weather agency to determine the information’s usefulness. If the pilot program proves fruitful, NOAA could place an order for more weather data from Spire and other commercial satellite startups to supplement measurements from government-owned satellites.

Orbital ATK’s next Cygnus cargo mission, known as OA-7, will launch on a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket in March, followed by the OA-8 mission due for liftoff on the company’s own Antares booster in the summer.

NASA has ordered at least 17 cargo missions from Orbital ATK under two multibillion-dollar contracts, and six of those flights are in the books with the successful re-entry Sunday.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.