European technicians working at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan have bolted an Italian-built Mars lander to its mothership ahead of a March 14 launch toward the red planet.

The attachment is a major step in preparations for next month’s launch the European Space Agency’s first mission to Mars since 2003, and the first of two flights for the agency’s ExoMars program, to be followed in 2018 or 2020 by the launch of an ambitious European rover to the red planet.

The ExoMars mission’s Trace Gas Orbiter, a large spacecraft with instruments probe the Martian atmosphere, will blast off with the Schiaparelli lander, which will try to become the first European platform to successfully operate on Mars.

The touchdown attempt in October will come nearly 13 years after Britain’s Beagle 2 lander was lost on decent to Mars in 2003.

Officials spotted Beagle 2 in imagery from NASA’s Reconnaissance Orbiter more than a decade later, showing the probe apparently intact on the Martian surface. Engineers who analyzed the images believe the lander’s solar arrays failed to unfurl properly, blocking Beagle 2’s antenna from radioing its status to Earth.

Schiaparelli is a larger, more technologically savvy spacecraft, fitted with advanced avionics, rocket thrusters, a guidance radar, and a European-made supersonic parachute.

Engineers transported the two ExoMars spacecraft from Turin, Italy, to Kazakhstan in December, and ground crews have worked on the orbiter and lander modules separately since they arrived at the launch base.

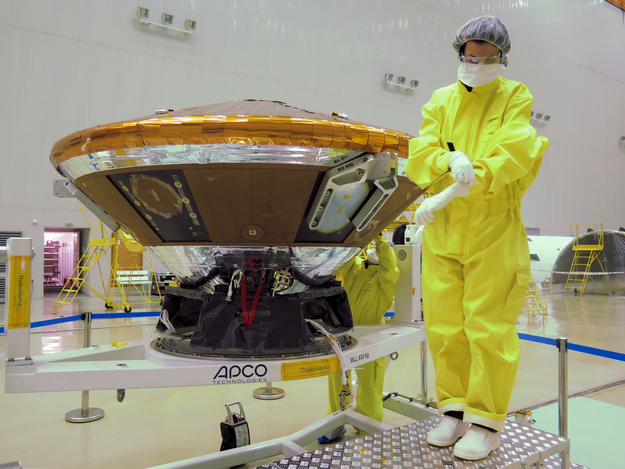

Activities to prepare the mission for launch since December include the fueling of the saucer-shaped Schiaparelli lander with hydrazine propellant and helium pressurant for its flight through the Martian atmosphere.

Technicians clad in hazardous materials suits loaded about 45 kilograms — nearly 100 pounds — of hydrazine into Schiaparelli’s three fuel tanks Jan. 30. The lander was already filled with the lightweight helium gas used to push the hydrazine fuel toward the lander’s nine small rocket engines.

The fueling with hydrazine gave the Schiaparelli lander — considered a technology demo mission by ESA — a full mass of about 600 kilograms, or more than 1,300 pounds. Schiaparelli’s purpose is to verify technologies to be put aboard the ExoMars rover launching no earlier than May 2018.

Schiaparelli’s braking thrusters will guide the lander’s descent after a supersonic parachute initially slows down the probe’s velocity during entry into the Martian atmosphere Oct. 19. The rocket jets will switch on at an altitude of about 1.3 kilometers — approximately 4,200 feet — above the surface, then switch off when Schiaparelli’s Doppler radar detects the craft is just 2 meters — about 6 feet — in altitude.

A crushable carbon fiber shell around the lander will cushion the probe’s fall to the surface, then Schiaparelli will turn on its weather station and return data to Earth for up to eight days until it drains its battery.

Engineers from ESA and Thales Alenia Space, builder of the Schiaparelli lander and Trace Gas Orbiter, prepared the descent probe for launch inside an ultra-clean tent enclosure designed to keep out contaminants and microbes that could accompany the mission on its seven-month trip to Mars.

Scientists want to avoid inadvertently sending microbes from Earth to Mars because they could ruin research into ancient Martian history aimed at determining whether the planet ever harbored life of its own.

The Baikonur Cosmodrome did not have facilities capable of such stringent modern “planetary protection” standards, officials said, so the ExoMars team brought extra gear to meet the cleanliness requirement.

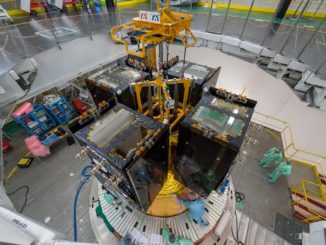

Workers hoisted Schiaparelli atop the Trace Gas Orbiter on Feb. 12 and mated the lander to its carrier craft with 27 screws, which connected a separation assembly between the two modules. When the lander deploys from the orbiter Oct. 16, three days before both spacecraft arrive at Mars, springs on the separation apparatus will push Schiaparelli away, according to a description posted on ESA’s website.

Technicians connected electrical cables between the lander and orbiter Feb. 13, followed by two days of checks to verify the spacecraft still functioned properly after their attachment.

Experts from Airbus Defense and Space responsible for Schiaparelli’s heat shield installed the lander’s final three thermal protection tiles after probe was perched atop the Trace Gas Orbiter.

The lander’s tiles are made of Norcoat Liège, a thermal ablative material composed of resin and cork, bonded to a carbon sandwich structure. Workers could not add the last tiles until Schiaparelli was in launch configuration because the heat shield covers hooks required to lift the lander atop the orbiter.

Primarily developed and financed by Italy, Schiaparelli could encounter temperatures as high as 3,360 degrees Fahrenheit (1,850 degrees Celsius) during the plunge through the Martian atmosphere.

With Schiaparelli now together with the Trace Gas Orbiter, the combined spacecraft stands more than 3 meters (10 feet) tall.

The next step to ready the spacecraft for launch will be the fueling of the orbiter with its own propellant supply in the coming week. The orbiter’s total propellant load will be about 2.3 metric tons — more than 5,000 pounds — giving the combined spacecraft a mass of 4.3 metric tons — about 9,480 pounds — at the time of liftoff.

While Schiaparelli heads for landing Mars, the mothership will fire its main engine to steer into orbit around the red planet, eventually settling into a circular orbit 400 kilometers, or about 250 miles, above the surface after a series of “aerobreaking” maneuvers to use the Martian atmosphere’s drag to lower its altitude.

The orbiter’s prime mission is to measure how much methane is in the Martian atmosphere, and trace the source the gas. The spacecraft will also relay commands and science data between Earth and landers on the surface of Mars, such as the ExoMars rover and NASA’s fleet of Martian robots.

Once ground teams fuel the orbiter, the ExoMars spacecraft will be added to a Breeze M rocket stage, which will propel the probe away from Earth after blasting off aboard a Russian Proton rocket.

ESA partnered with Russia for the ExoMars program after NASA withdrew due to budget constraints.

The ExoMars 2016 mission is set for liftoff at 0931 GMT (5:31 a.m. EDT) on March 14, the opening of a 12-day launch window.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.