Getting off to a ground-shaking start, NASA’s $1.2 billion Psyche asteroid probe roared into space atop a Falcon Heavy rocket Friday, setting off on a 2.2-billion-mile voyage to a rare, metal-rich asteroid that may hold clues about how the cores of rocky planets like Earth first formed.

“We’re going to learn about a previously unstudied ingredient that went into making our habitable Earth, and that is the metal that is now in the Earth’s core and the cores of all of the rocky planets, cores that we can never visit but of course that we want to learn about,” said Principal Investigator Lindy Elkins-Tanton.

“And Psyche is the single largest metallic object in our solar system. So if we want to learn about our cores, that’s where we need to go.”

Following multiple setbacks and delays in the wake of the Covid pandemic — and a 24-hour slip due to stormy weather Thursday — the Psyche mission finally got under way at 10:19 a.m. EDT when the SpaceX Falcon Heavy’s 27 first-stage engines ignited with a thundering rush of flaming exhaust.

After a final round of lightning-fast computer checks, the 230-foot-tall rocket was released from historic pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center, smoothly climbing away atop more than 5 million pounds of thrust.

The Falcon Heavy’s two strap-on side boosters shut down and peeled away two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff and flew back to staggered side-by-side landings at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. The expendable central core booster continued firing another minute and a half before it, too, fell away.

The single engine powering the rocket’s second stage then took over the climb to space. After a 45-minute coast, the engine fired a second time, putting the vehicle on the required Earth-escape trajectory. The 6,000-pound Psyche probe was released to fly on its own six minutes later, kicking off a six-year voyage to the asteroid it was named after.

Discovered in 1852 by the Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis, 16 Psyche is the largest of nine known metal-rich asteroids, orbiting in the outer asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter three times farther from the sun than Earth.

Radar observations show it’s shaped roughly like a potato, measuring 173 miles across and 144 miles long, but it only appears as a star-like dot in even the most powerful telescopes. Scientist know from spectral and other observations that its metal content is high.

“We’re quite confident that it is largely made of metal along with something else,” said Elkins-Tanton. “That’s something else might be rock, it might be sulfur based and it might be carbon based. We don’t know. And that is really the excitement of this.”

Earlier in the project, a reporter asked her how much an asteroid like Psyche might be worth given its high metal content. The numbers ranged as high as $10 quintillion.

“It’s my fault, because I did do that calculation,” Elkins-Tanton said. “It makes such a great headline. But it’s false in every way. We have zero technology to bring Psyche back to Earth. And if we did, it would likely be a catastrophic mistake. It would flood the metals market and it would literally be worth nothing. And so calculating the value of it (is) a fun intellectual exercise with no truth to it.”

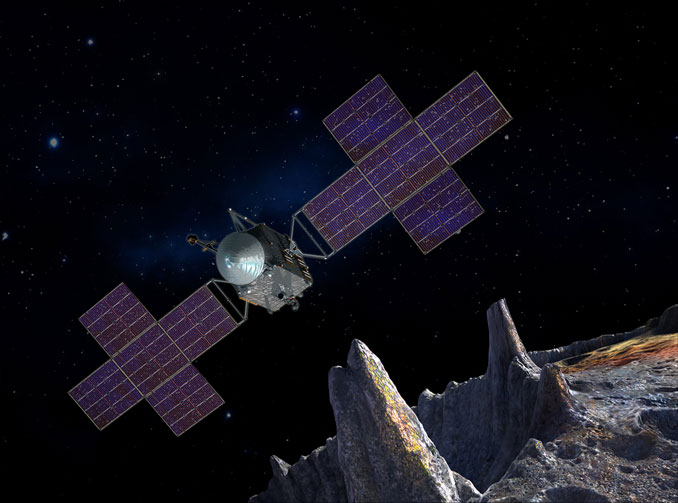

Likewise, an artist’s impression of the asteroid, based on guidance from Elkins-Tanton and the latest thinking about remnant planetary cores. While the image is “plausible for what we suspect,” she said, it’s “not real, because we don’t know what it looks like.”

Or how it formed in the first place. There are two leading theories.

“One is that it’s a core of a body, analogous to like what is inside the Earth, with a molten metallic center,” said Ben Weiss, Psyche deputy principal investigator at MIT. “But in this case, Psyche had its outer layers stripped off by asteroid impacts in the early solar system, so we can see (the exposed core) today.

“The other idea is that Psyche is a kind of primordial, unmelted body, basically formed from the very first materials in the solar system that (has been) preserved in this primordial state ever since.”

The Psyche spacecraft, built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using a modified satellite body provided by Maxar, will attempt to answer those questions and many more during 26 months of close-range observations using a suite of sophisticated instruments.

The probe is equipped with two multi-spectral cameras to map the surface in exquisite detail, two magnetometers to measure whatever magnetic field might be frozen in the once liquid metal, a gamma ray and neutron mass spectrometer to chart the asteroid’s chemical composition and a radio science experiment to measure its gravitational field.

But it will not be easy. And it will not be quick.

To reach its quarry, the spacecraft will use solar electric propulsion electrically accelerating ionized xenon atoms in any one of four Hall-effect thrusters to produce a gentle but constant push.

Psyche will launch with 2,392 pounds of xenon in seven 22-gallon tanks. The electrical power to strip away electrons and ionize the fuel will come from two five-panel solar wings capable of generating 21 kilowatts near Earth, dropping to between 2.3 and 3.4 kilowatts at Psyche’s distance from the sun.

“You can think of this as getting thrust from sunlight,” said David Oh, Psyche’s chief engineer for operations at JPL. “It’s the ultimate in green propulsion for our spacecraft.”

Unlike chemical propulsion rocket engines, which consume propellant in fuel-gulping bursts of high power, Hall effect thrusters produce vastly less thrust, roughly equivalent to the weight of three quarters. But they can run around the clock, slowly but surely building up speed while getting about 10 million miles per gallon.

After three to four months of testing and checkout, Psyche will loop out toward Mars, flying past the red planet in May 2026 at an altitude between 1,900 and 2,700 miles for a gravity assist flyby that will boost the spacecraft’s velocity from about 45,600 mph relative to the sun to about 52,22 mph.

Along the way to Mars, engineers will put a hitchhiker payload through its paces: the Deep Space Optical Communications, or DSOC, experiment. An infrared laser and telescope assembly attached to the side of the Psyche spacecraft will attempt to send data back to Earth at vastly higher rates than possible with traditional radio signals.

Laser communications have been tested around the moon, but DSOC is the first to be used in deep space. At such distances, sending signals back to the 200-inch Hale telescope at Mount Palomar in California is roughly equivalent to hitting a dime at a distance of one mile.

“We’re very excited about launch and looking forward to the important lessons learned, which will in the future enable human missions to Mars and the use of very high resolution instruments,” said Abi Biswas, a DSOC manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The Mars flyby will send Psyche spiraling outward, slowly but surely catching up with its target. In May 2029, the spacecraft’s cameras will begin imaging the asteroid, using the data to fine tune its approach.

Two months later, after a voyage covering 2.2 billion miles, Psyche will be close enough to be captured by the asteroid’s feeble gravity.

Four basic orbital altitudes are planned, starting at an height of about 441 miles above the surface, then dropping to 188 miles and finally to less than 50 miles before moving back out to an altitude of about 118 miles.

Throughout, Psyche’s cameras will map the surface at higher and higher resolutions, magnetometers will chart the asteroid’s magnetic field while scientists on Earth measure its gravitational field by studying minute changes in the spacecraft’s velocity as seen in subtle changes in the radio signals sent back to Earth.

At its lowest altitude of about 45 miles, the probe’s gamma ray and neutron spectrometer will characterize the mineral composition across the asteroid’s surface.

The final set of orbital observations is expected to begin in mid January 2031. Psyche’s prime mission is expected to end on Nov. 1, 2031.