While SpaceX’s next crew mission awaits a launch opportunity just up the coast, another Falcon 9 rocket is poised for liftoff from Cape Canaveral Thursday with another cluster of 53 Starlink internet satellites heading for a deployment orbit nearly 200 miles above Earth.

SpaceX’s launch team at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station rolled the Falcon 9 from its hangar to pad 40 Wednesday, then raised the 229-foot-tall (70-meter) rocket in its starting blocks Wednesday night.

After completing overnight launch preparations, SpaceX will begin loading super-chilled, densified kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants into the Falcon 9 about 35 minutes before liftoff.

Launch is set for 11:14 a.m. EDT (1514 GMT) Thursday to begin SpaceX’s 42nd launch primarily dedicated to hauling satellites into orbit for the company’s privately-funded Starlink internet network.

There is a 70% chance of favorable weather for launch Thursday morning, according to the U.S. Space Force’s 45th Weather Squadron. The primary weather concern Thursday is ground winds at Cape Canaveral, which are forecast to gust up to 22 mph from the east.

Otherwise, the weather team predicts conditions will be favorable for launch, with a partly cloudy sky, good visibility, and a temperature around 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

The mission, named Starlink 4-14, will be SpaceX’s 15th Falcon 9 launch of the year, and the 149th flight of a Falcon 9 rocket since the workhorse launcher debuted on June 4, 2010.

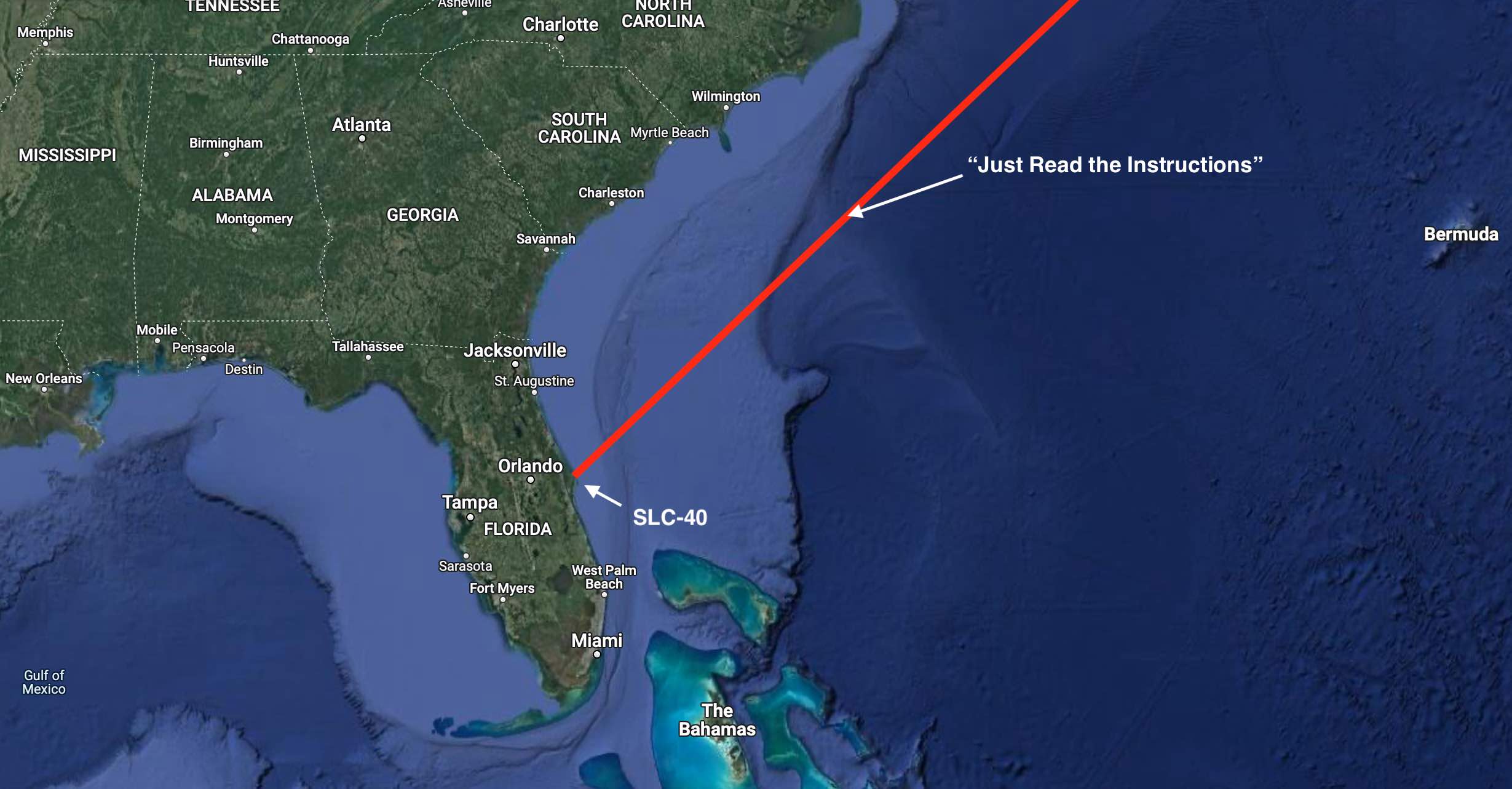

Following a familiar profile for launch-watchers, the Falcon 9 will head northeast from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, soaring through the atmosphere downrange over the Atlantic Ocean. The rocket’s nine Merlin 1D engines will produce about 1.7 million pounds of thrust at full power.

The engines will switch off and the booster will separate from the second stage of the Falcon 9 about two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff. The second stage’s single Merlin engine will fire to push the 53 Starlink payloads into a preliminary parking orbit, while the booster configures itself for a scorching-hot plunge back into the atmosphere.

The first stage will extend four titanium hypersonic grid fins to help steer itself through the rarefied upper atmosphere. An entry burn using three of the first stage engines, then a final braking burn using a single engine, will slow the rocket for landing on the football field-sized drone ship “Just Read the Instructions.”

The landing platform will be positioned in the Atlantic Ocean a few hundred miles east of Charleston, South Carolina. After the rocket lands, the drone ship will return the 15-story-tall booster to Cape Canaveral for refurbishment.

The booster flying on Thursday’s mission will make its 12th flight to space, tying a record number of flights for SpaceX’s reusable rocket fleet. The rocket — tail number B1060 — first launched June 30, 2020, with a U.S. military GPS navigation satellite.

Most recently, the booster launched March 3 with a previous batch of Starlink internet satellites.

The Falcon 9’s upper stage engine is expected to shut down nearly nine minutes into the mission, moments after the scheduled landing of the first stage downrange in the Atlantic Ocean.

After coasting across the North Atlantic, over Europe and the Middle East, then across the Indian Ocean, the upper stage is programmed to reignite its engine for a brief one-second firing to maneuver the 53 Starlink satellites into the proper orbit for separation.

The Falcon 9’s guidance computer will aim to release the flat-panel satellites just shy of one hour after launch in an orbit between 189 miles and 197 miles (304 by 318 kilmeters) above Earth, with an inclination of 53.2 degrees to the equator.

The Starlink satellites will extend solar arrays and use on-board ion thrusters to reach their operational orbit at an altitude of 335 miles (540 kilometers), where they will enter commercial service for SpaceX.

SpaceX has launched 2,335 Starlink satellites to date. Around 2,067 of those satellites are still in orbit and appear to be working, and the rest have either failed or fallen out of orbit, according to a list maintained by Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist who closely tracks spaceflight activity.

That’s nearly five times the number of satellites currently flying in the second-largest fleet of spacecraft — the internet constellation owned by Starlink rival OneWeb. In third place is Planet, which operates a fleet of more than 200 small Earth-imaging satellites.

SpaceX is in the midst of launching around 4,400 Starlink satellites into five orbital “shells” more than 300 miles above Earth. The shells are positioned at different inclinations, and SpaceX completed launches of the first of the five Starlink groups last May.

Ultimately, SpaceX intends to launch as many as 42,000 internet satellites. The final figure hinges on market demand for the Starlink service, which offers high-speed, low-latency connectivity.

SpaceX says the service is best suited for customers in remote, hard-to-reach areas, such as rural communities, isolated homes, islands, and ships. Customers can sign up for Starlink service online by paying a reservation fee and paying $599 for an antenna and modem. SpaceX charges $110 per month for consumer-grade Starlink service.

SpaceX has partnered with the U.S. military to demonstrate Starlink connectivity to airplanes. Delta Air Lines has also conducted “exploratory” tests of the Starlink system for possible future use on passenger aircraft, according to the Wall Street Journal.

The launch of the Starlink 4-14 mission will be followed by the flight of another Falcon 9 rocket currently standing on pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, a few miles north of the pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

The launch from pad 39A will carry four astronauts into orbit aboard SpaceX’s Dragon Freedom spacecraft on NASA’s Crew-4 mission to the International Space Station. The launch is scheduled for no earlier than next Tuesday, April 26, three days later than previously planned due to weather delays that have pushed back the return of another SpaceX Dragon crew capsule from the space station.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.