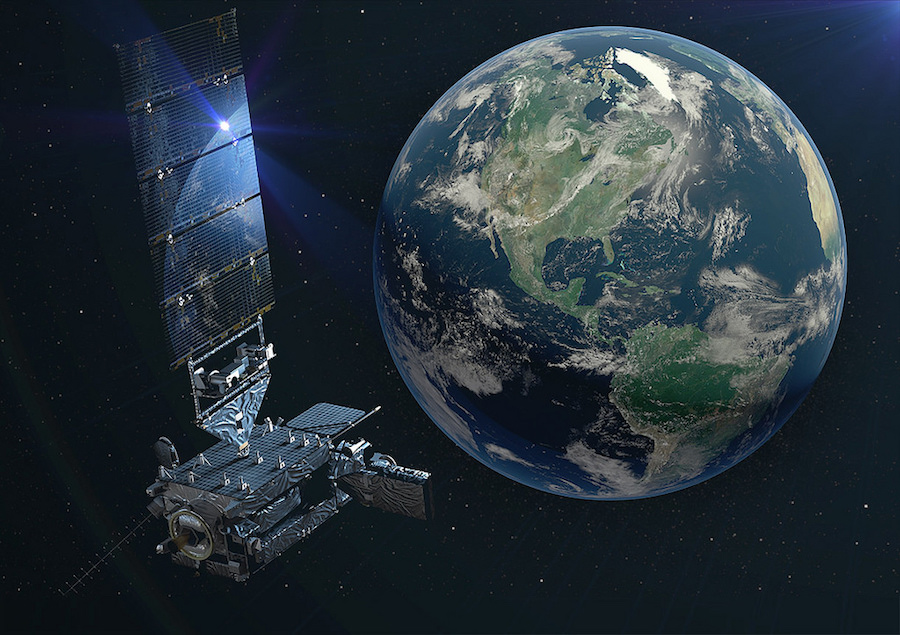

A new NOAA weather satellite destined to track cyclones, wildfires, and solar flares from a perch high above the Western United States and Pacific Ocean is set for liftoff Tuesday from Cape Canaveral on a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The GOES-T satellite will launch with modifications to its main imaging camera, changes designed to avoid a minor cooling system problem that afflicted NOAA’s previous geostationary weather monitor sent into space four years ago.

The spacecraft is enclosed inside the nose cone of an Atlas 5 rocket, poised for blastoff during a two-hour launch window opening at 4:38 p.m. EST (2138 GMT) Tuesday. There is a 70% chance of good weather for launch.

The GOES-T satellite is the third in a series of four new NOAA weather observatories with more advanced instruments to funnel data and images to weather forecasters across the United States and the rest of the Americas.

NOAA’s fleet of Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites, or GOES program, tracks hurricanes, severe storms, wildfires, dust storms, and other weather events in real-time, giving forecasters a minute-by-minute glimpse of evolving conditions.

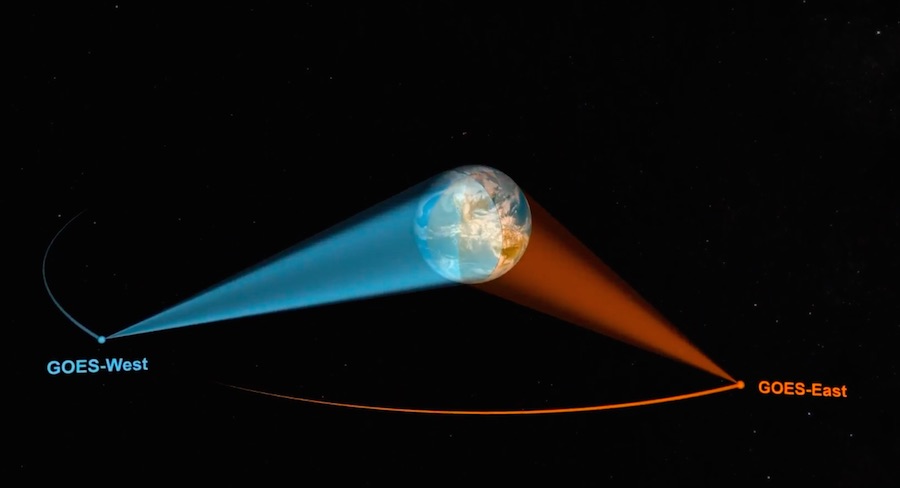

The satellites are parked in geostationary orbit more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator, where they orbit Earth in lock-step with the planet’s rotation. NOAA maintains one operational GOES satellite in a western position over the Pacific Ocean and Western United States, and another GOES spacecraft in an eastern slot to cover the Eastern United States, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic Ocean.

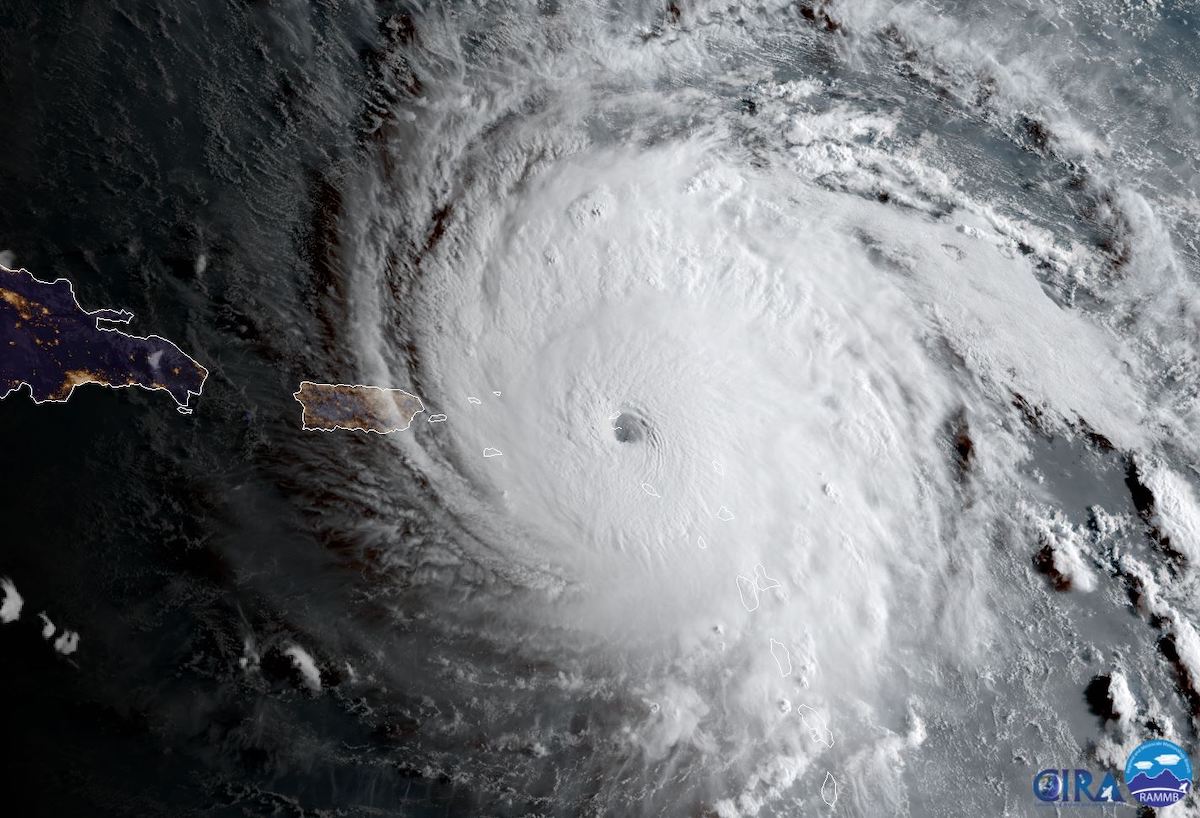

The GOES spacecraft produce the sharpest real-time weather satellite views of hurricanes and storms used in television broadcasts. The first GOES satellite launched from Cape Canaveral in 1975. NOAA also operates a constellation of lower-altitude satellites in polar orbit for aid in medium- and long-term forecasting.

“NOAA’s geostationary satellites provide the only continuous coverage of weather and hazardous environmental conditions in the Western hemisphere, protecting the lives and properties of the 1 billion people who live and work there,” said Pam Sullivan, NOAA’s director of GOES-R program, which includes the GOES-T mission. “The observations from these satellites are even more critical now when the U.S. is experiencing a record number of billion dollar disasters.”

Built by Lockheed Martin in Colorado, GOES-T is heading to the GOES-West location in NOAA’s fleet, where it will be parked at 137 degrees west longitude. NOAA will rename the satellite GOES-18. It will replace GOES-17, formerly known as GOES-S, which launched in March 2018 and has been in the GOES-West position since 2019.

The first satellite in NOAA’s latest weather satellite series — GOES-R, now GOES-16 — launched in 2016 and is operational covering the U.S. East Coast and Atlantic Ocean region, an area ripe for hurricane development.

GOES-17 suffers from degraded performance in its Advanced Baseline Imager, the satellite’s main instrument.

The ABI is made by L3Harris in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and is designed to resolve more detail in storm clouds than any previous operational weather instrument in geostationary orbit.

The camera can capture images at a faster cadence than previous GOES satellites — hemispheric views every 15 minutes, and imagery of the continental United States every five minutes. The GOES-R series of satellites can return pictures of hotspots like hurricanes at a cadence of once every 30 seconds, an improvement from the five-minute rapid scans available before 2016.

It is also able to see in 16 channels, ranging from infrared to visible wavelengths, up from five channels on the imager carried aboard the previous generation of GOES satellites.

Engineers noticed degraded vision in the imager on GOES-17 a couple of months following its launch. An investigation traced the most likely cause of the problem to foreign object debris blocking the flow of coolant in the instrument’s thermal control system. The cooling system malfunction means the instrument’s detectors are unable to stay at the proper temperatures at certain times, leading to intermittent loss of some infrared imagery.

Ground teams were able to recover some of the instrument’s lost function. NOAA now says the imager is collecting about 97% of its planned data, with most image problems confined to times when the satellite is exposed to specific thermal conditions.

“GOES-17 is still a very capable satellite,” Sullivan said in a pre-launch press conference.

Despite the imager problem, NOAA activated GOES-17 in the GOES-West position because it still outclassed the older satellite previously occupying that location in the fleet. But GOES-T, soon to be GOES-18, will offer even better coverage.

GOES-17 will be transitioned to a backup satellite in NOAA’s fleet.

The imagers on GOES-T and the next satellite in the series, GOES-U, have been modified to prevent a recurrence of the foreign object debris, or FOD, problem. Engineers changed the radiator design to eliminate filters where foreign object debris can become trapped.

After the problem on GOES-17, managers sent the already-finished ABI on GOES-T back to L3Harris for rework.

“Basically, the hardware that was at fault, or we determined was the most likely cause for that FOD, has been eliminated from that design,” said Larry Crawford, ABI program manager at L3Harris.

“The GOES-T satellite is very similar to its older siblings but has design changes incorporating lessons learned from GOES-R and -S on orbit,” Sullivan said.

The GOES-T satellite has an upgraded magnetometer instrument provided by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and instruments to monitor solar flares and radiation in the space environment near Earth.

Like the most recent two GOES spacecraft, GOES-T also carries a lightning mapper to detect and locate lightning strikes within the satellite’s field-of-view. The spacecraft hosts a transponder to receive and relay distress messages, part of a global space-based search and rescue repeater network.

NASA partners with NOAA on development of weather satellites, overseeing contracts to develop the spacecraft, instruments, and procure launch vehicles. NOAA operates and owns the satellites.

The GOES-R program is costing $11.7 billion, including expenditures for four satellites, instruments, launch services, and operations, according to Sullivan.

From its location with visibility over the Western United States, GOES-T will be able to detect thermal signatures and smoke plumes from wildfires, which have ravaged large areas of territory during recent fire seasons.

“GOES-West is in an ideal position out there to get a really close look at those fires,” said Dan Lindsey, NOAA’s GOES-R program scientist.

“It’s almost impossible to overstate what a significant factor GOES-T will be in the forecasting and responding to wildfires,” said James Yoe, chief administrator for the Joint Center for Satellite Data Assimilation.

The satellite’s instruments can monitor the health of vegetation before and after fires. The lightning mapper will help analysts locate where fires might occur. Lightning is a common natural cause of brush and grass fires in dry regions.

GOES-T will also be well positioned for tracking volcanic plumes over the West Coast and the Pacific Ocean, and will allow meteorologists to follow “atmospheric rivers,” huge plumes of moisture that stream across the Pacific toward North America, the source of floods, which can ultimately spawn natural disasters like landslides.

The satellite will also be useful for gathering data for numerical weather models used in global forecasting. And because most weather systems move west to east, GOES-T will see weather systems before they affect other parts of the United States east from its coverage zone.

The GOES-T satellite will ride ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket into an elongated, or elliptical, transfer orbit using three burns of the launcher’s Centaur upper stage. Deployment of the GOES-T spacecraft from the Atlas 5 rocket is planned around three-and-a-half hours into the mission, then GOES-T will use its own engine to reach a circular geostationary orbit.

The new spacecraft begin a nearly year-long series of checkouts and tests before NOAA declares it operational. The first weather images from GOES-T — the future GOES-18 — could come down in May, and data from the new satellite could be provided to National Weather Service forecasters on a provisional basis as soon as July.

The satellite should be fully operational by early 2023.

GOES-T is designed for a service life of at least 15 years, and the four GOES-R series satellites will extend NOAA’s geostationary weather satellite coverage capability through the 2030s. GOES-U, the final satellite of the current batch, is scheduled to launch in 2024 on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.