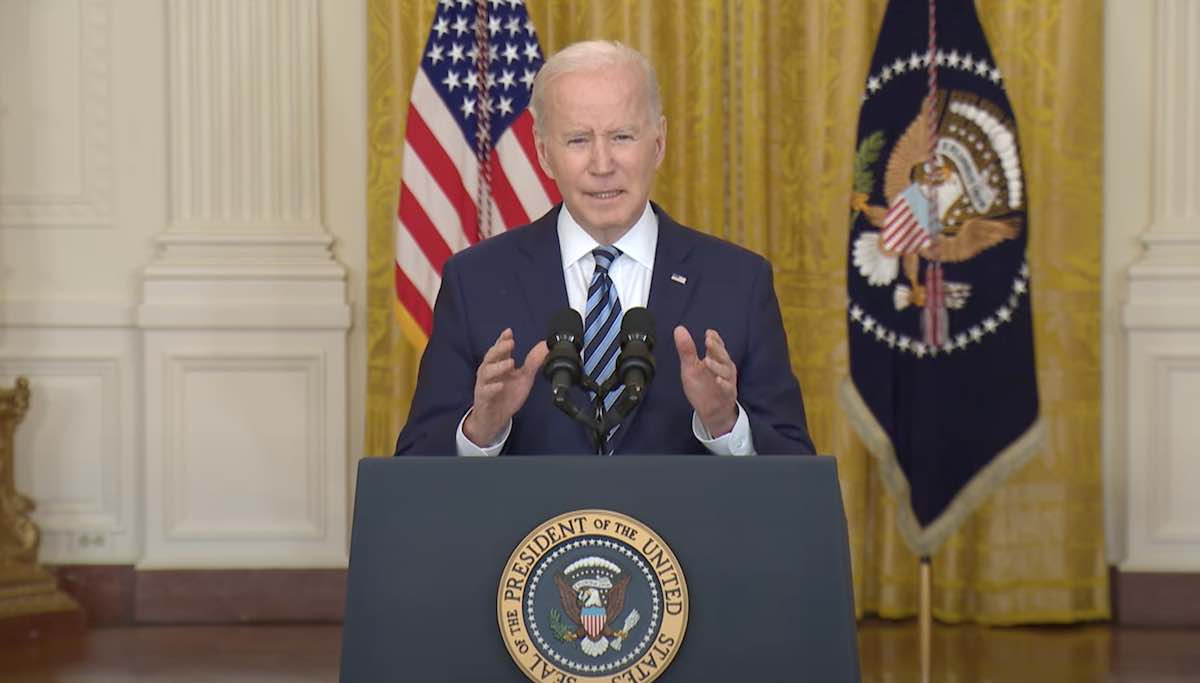

President Biden said Thursday the United States is imposing new sanctions against Russia, including measures that will “degrade” the country’s space program, in response to Russian military attacks on Ukraine.

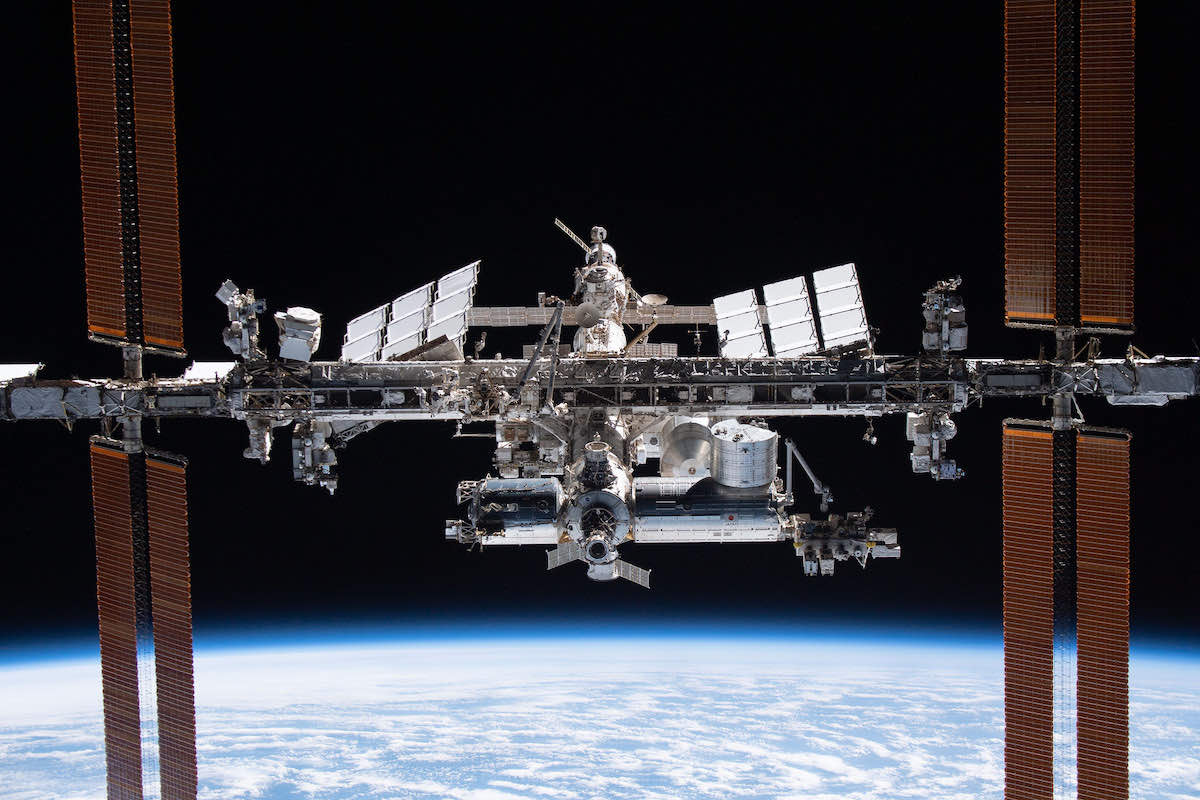

So far, operations and training for future missions on the International Space Station are proceeding without interruption, according to NASA. The space station, an investment of more than $100 billion in U.S. taxpayer funding, has been continuously staffed by U.S. and Russian crew members since 2000.

NASA said in a statement that the new export control measures against Russia announced Thursday “will continue to allow U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation.”

“No changes are planned to the agency’s support for ongoing in orbit and ground station operations,” NASA said.

Relations between the United States and Russia have frayed since the dawn of the space station program. But the space station remains one of the most significant geopolitical partnerships left between the two countries.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine Thursday could threaten the long-term future of the partnership.

Biden himself singled out Russia’s space program in a speech Thursday, alongside other sectors of the Russian economy targeted by new sanctions. Biden said the measures will have “severe costs” on the Russian economy and are “purposely designed” to maximize long-term impacts on Russia.

“Between our actions and those of our allies and partners, we estimate that we’ll cut off more than half of Russia’s high tech imports and will strike a blow to their ability to continue to modernize their military,” Biden said. “It’ll degrade their aerospace industry, including their space program.”

Biden said the sanctions also targeted Russia’s military, maritime industry, financial institutions and Russian citizens close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The sanctions, in sum, will be a “major hit to Putin’s long term strategic ambitions, and we’re preparing to do more,” Biden said.

A White House fact sheet on the new sanctions does not explicitly mention Russia’s space program, but discusses a ban on exports on “sensitive technology” to Russia’s defense, aviation, and maritime sectors.

“This includes Russia-wide restrictions on semiconductors, telecommunication, encryption security, lasers, sensors, navigation, avionics and maritime technologies,” the White House said.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who also announced his country was introducing new sanctions against Russia, was asked about the International Space Station program Thursday in the House of Commons.

He said he has been in favor of continuing “artistic and scientific collaboration” with Russia. “But in the current circumstances, it’s hard to see how even those can continue as normal,” Johnson said.

Dmitry Rogozin, head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, tweeted a series of messages Thursday shortly after Biden’s remarks, but before NASA’s clarification that the new sanctions won’t impact civilian cooperation in space.

“Biden said the new sanctions would affect the Russian space program,” Rogozin tweeted, according to an online translator. “OK. It remains to find out the details: 1. Do you want to block our access to radiation-resistant space microelectronics? So you already did it quite officially in 2014.”

Rogozin was apparently referring to sanctions introduced by the Obama administration after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

“As you noticed, we, nevertheless, continue to make our own spacecraft,” Rogozin added. “And we will do them by expanding the production of the necessary components and devices at home.

“2. Do you want to ban all countries from launching their spacecraft on the most reliable Russian rockets in the world? This is how you are already doing it and are planning to finally destroy the world market of space competition from January 1, 2023, by imposing sanctions on our launch vehicles. We are aware. This is also not news. We are ready to act here, too.

“3. Do you want to destroy our cooperation on the ISS? This is how you already do it by limiting exchanges between our cosmonaut and astronaut training centers. Or do you want to manage the ISS yourself? Maybe President Biden is off topic, so explain to him that the correction of the station’s orbit, its avoidance of dangerous rendezvous with space garbage, with which your talented businessmen have polluted the near-Earth orbit, is produced exclusively by the engines of the Russian Progress MS cargo ships.”

In this tweet, Rogozin’s reference to “space garbage” seems to be aimed at SpaceX’s Starlink internet network. More than 2,100 Starlink satellites have launched to date for the global internet network run by Elon Musk’s space company, making Starlink the largest fleet of spacecraft ever put into orbit.

SpaceX’s Starlink network, along with other commercial satellite “mega-constellations” have been criticized before. Rogozin didn’t mention a Russian anti-satellite missile test last year that added thousands of pieces of space junk to busy orbital traffic lanes a few hundred miles above Earth.

NASA and Roscosmos are the two largest partners on the International Space Station, which could not easily operate without critical contributions from U.S. and Russian modules. The U.S. segment of the station generates the bulk of the lab’s electrical power and maintains the pointing of the complex in orbit.

Russia’s modules and Progress supply ships are the primary source of propulsion, maintaining the lab’s altitude and occasionally steering the space station out of the way of space debris. Russia is also planning to oversee the de-orbiting and disposal of the huge station — the largest spacecraft ever put into orbit — into the unpopulated ocean at the end of its service life, currently expected around 2030.

A Northrop Grumman Cygnus cargo freighter that arrived at the space station Monday will debut a new U.S. capability to reboost the orbit of the complex. But the Cygnus spacecraft is not intended to maneuver the space station away from space junk, or make major orbit adjustments.

“If you block cooperation with us, who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit and fall into the United States or Europe? There is also the option of dropping a 500-ton structure to India and China. Do you want to threaten them with such a prospect? The ISS does not fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours,” Rogozon tweeted Thursday. “Are you ready for them? Gentlemen, when planning sanctions, check those who generate them for illness Alzheimer’s. Just in case. To prevent your sanctions from falling on your head. And not only in a figurative sense.”

“Therefore, for the time being, as a partner, I suggest that you do not behave like an irresponsible gamer, disavow the statement about ‘Alzheimer’s sanctions.’ Friendly advice.”

Early Friday, after NASA signaled its intention to continue with Russia on the space station program, Rogozin tweeted: “As diplomats say, ‘our concerns have been heard.’”

“NASA confirmed its willingness to continue to cooperate with Roscosmos through ISS,” Rogozin tweeted. “In the meantime, we continue to analyze the new U.S. sanctions to detail our response.”

Rogozin’s aggressive and sarcastic tone is nothing new.

In 2014, in the wake of sanctions levied following Russia’s earlier incursion into Ukraine, Rogozin ridiculed claims that he personally profited from Russia’s space industry. Rogozin was placed on the U.S. sanctions list at the time, when was a Russian deputy prime minister overseeing the country’s defense and aerospace industries.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 helped trigger a review of the the U.S. space industry’s use of Russian components.

The crisis hastened a move away from the U.S. military’s use of United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rockets, which are powered by Russian RD-180 main engines. ULA is retiring the Atlas 5 and is developing a replacement rocket, Vulcan Centaur, with U.S.-made engines produced by Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’s space company.

NASA was already working with SpaceX and Boeing on new human-rated crew ferry capsules.

“After analyzing the sanctions against our space industry, I suggest the U.S. delivers its astronauts to the ISS with a trampoline,” Rogozin tweeted in 2014.

Rogozin was referring to NASA’s use of Russian Soyuz spacecraft to ferry U.S. and allied astronauts to and from the International Space Station. During a gap on U.S. human spaceflight capability following the retirement of the space shuttle, NASA purchased seats on Soyuz crew capsules to transport astronauts until SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spaceship began launching crews to the station in 2020.

“The trampoline is working!” Musk joked after SpaceX’s first crew launch.

With SpaceX’s crew transportation capability now operational, and a Boeing crew capsule in testing, NASA is less reliant on Russia’s space program than it was in 2014, but is not entirely free of Russian influence.

NASA said in a statement Thursday that it continues working with international partners, including Russia, “to maintain safe and continuous International Space Station operations.”

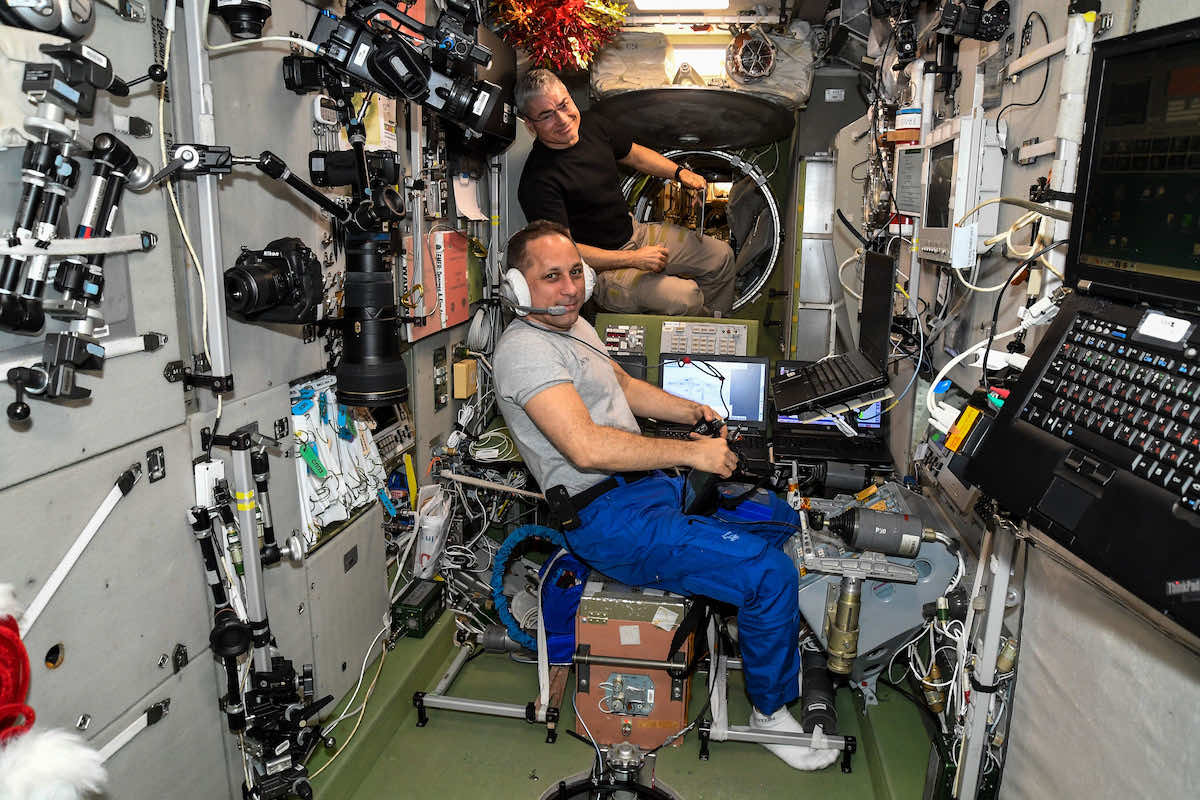

A crew of seven is currently living and working on the station — four U.S. astronauts, two Russian cosmonauts, and a European Space Agency flight engineer.

A team of three Russian cosmonauts is scheduled to launch to the space station March 18 on a Soyuz rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. They will replace NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei, current station commander Anton Shkaplerov, and cosmonaut Pyotr Dubrov scheduled to return to Earth on a different Russian Soyuz spacecraft March 30.

Vande Hei and Dubrov will close out a 355-day mission on the space station, a record for a single spaceflight by a U.S. astronaut.

Training continues for future space station expeditions, NASA said.

“Two NASA astronauts completed training in Russia earlier in February prior to returning home,” the agency said in a statement. “As scheduled, there are three cosmonauts currently training at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston for space station missions.”

David Burbach, a professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College, said near-term ISS operations are not likely to be impacted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“The station is so interconnected, the two countries so interdependent, there’s not much middle ground between cooperating or irreversibly abandoning ISS (and as Roscosmos head Dmitiry Rogozin tweeted today, then the 500 ton station reentering uncontrolled),” Burbach wrote in an email to Spaceflight Now.

“I’m sure the U.S. doesn’t want that, and I don’t think Putin wants it,” Burbach wrote, noting he was commenting on a personal basis, and not on behalf of the Navy. “That said, Putin is not much worried about international prestige, and Russia’s human spaceflight program does not pay off in prestige or in cash the way it used to. I suspect ISS is less important to Russia today than Americans are used to thinking, but still somewhat important.”

But the deterioration in U.S.-Russia relations could drive the countries’ space programs apart over time, and make the start of future cooperative projects unlikely, he said.

“Longer term, this change in relations makes it somewhat more likely that ISS is terminated sooner than 2030, and I’m sure will raise interest in the U.S. in encouraging the development of commercial stations,” Burbach wrote.

“Sanctions and the break in relations are likely to impact commercial and scientific engagement with Russia,” he wrote. “I can’t imagine ESA or NASA agreeing to new joint projects with Roscosmos anytime soon. Russia was already a declining presence in the commercial launch market, and whether due to sanctions or avoiding political risk, it’s unlikely they’ll get new business from Western companies.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.