STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

Sixty years after NASA astronaut Alan Shepard became the first American in space, his oldest daughter plans to blast off Saturday on a sub-orbital flight of her own, joining former NFL star and TV host Michael Strahan, two entrepreneurs and a father-and-son duo aboard a Blue Origin New Shepard spacecraft.

“It’s kind of fun for me to say an original Shepard will fly on the New Shepard,” Laura Shepard Churchley said in a video tweeted by Blue Origin.

“I’m very proud of my father’s legacy,” she added. “He was the first American in space and the fifth man on the moon and so far, has been the only man to play golf on the moon. I believe he would say the same thing as my children: Go for it, Laura.”

Blastoff from Blue Origin’s West Texas launch site, near the small town of Van Horn, is currently targeted for 9:45 a.m. EST Saturday, weather permitting. The flight was originally scheduled for Thursday but was postponed due to high winds.

If all goes well, the New Shepard rocket will propel the passengers to an altitude of just above 62 miles, the internationally recognized “boundary” between the discernible atmosphere and space.

The six crew members will enjoy three to four minutes of weightlessness — and jaw-dropping views — before a parachute descent to Earth to close out a 10-minute up-and-down flight.

The 19th New Shepard mission — NS-19 — will be Blue Origin’s third flight with passengers on board, and the first with a full six-member crew. Blue Origin owner Jeff Bezos, his brother Mark, 82-year-old aviation pioneer Wally Funk and Dutch teenager Oliver Daemen took off July 20 on the company’s first such flight.

Churchley and Strahan, a retired Hall of Fame professional football player and co-anchor of ABC’s “Good Morning America,” are flying as guests of Blue Origin. Their four crewmates — Lane Bess and his son, Cameron, Evan Dick and Dylan Taylor — bought their tickets for undisclosed amounts.

As might be expected, Strahan is the “star” of New Shepard flight 19, while Churchley’s quest to follow in her father’s footsteps is generating widespread interest among space enthusiasts and history buffs.

Alan Shepard, one of NASA’s original Mercury 7 astronauts, became the first American to fly in space when he blasted off on May 5, 1961, three weeks after cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin rocketed into history as the first human to reach orbit. Shepard went on to walk on the moon as commander of the Apollo 14 mission in 1971, famously hitting a golf ball during a moonwalk.

In an interview on “Good Morning America,” Strahan asked Churchley what she was most excited about.

“I’m excited to kind of be following in my father’s footsteps, for starters,” she said. “And I’m excited just to go up into space to see what it all looks like. I’ve been looking at stars with my father forever, and now we’re all going to get really close. And it’s just going to be thrilling.”

he other crew members are relative unknowns on the public stage, although Taylor is an active and widely respected space investor and enthusiast.

In an interview with The Miami Herald, Bess, founder of Bess Ventures and Advisory, a fund that invests in high-technology startups, said he anticipates a “Zen moment” as he soars out of the atmosphere.

“We deal with COVID, political unrest and even the challenges of a business career,” he told the Herald. “But when you look at the bigger perspective, you hopefully get this appreciation: How much do these things matter in the longer scheme of our planet and life and where we come from? … I will have the picture of the view that I’ll have looking out the window in my mind for the rest of my life.”

Taylor, one of the world’s most active private space investors and a co-founding patron of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, said on his web page he never dreamed, while growing up in rural Idaho, that he might one day fly in space himself.

“I thought spaceflight was a possibility that only a handful of astronauts could achieve, and I could have never imagined that would someday include me,” he wrote in a blog post.

“To be one of just 600 humans to (travel) into space since the beginning of time? How could this even be possible? What an extraordinary privilege. But as many of us believe, with great privilege comes great responsibility.”

He said he planned to donate the price he paid for a ticket to multiple charities and encouraged other commercial space travelers to do the same. He calls it “buy one, give one.”

“It is simple, donate to worthy causes here on Earth the equivalent of the ticket price for the spaceflight,” he wrote. “Commercial astronauts are predicted to spend several hundred million dollars in the next five years. The impact that cohort could have here on Earth if they all supported this initiative could be very substantial.”

Competition for private spaceflight

The NS-19 mission marks the seventh piloted commercial, non-government sub-orbital spaceflight in a high-stakes competition between Bezos’ Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, owned by fellow billionaire Richard Branson.

Virgin has launched four piloted flights of its winged spaceplane VSS Unity, most recently sending up Branson, two pilots and three company crewmates on July 11. It’s not clear when the company will stage its next flight, but three researchers will be on board representing the Italian air force. Commercial passenger flights are expected to begin next year.

Blue Origin followed up the Bezos flight by launching a suite of NASA experiments on an unpiloted mission August 26. Then, on October 13, actor William Shatner — Captain Kirk of “Star Trek” fame — and three crewmates were launched on the company’s 18th flight overall and the second with passengers aboard.

“What you have given me is the most profound experience I can imagine,” he told Bezos, on the verge of tears, after the flight. “I’m so filled with emotion about what just happened. I just, it’s extraordinary, extraordinary. I hope I never recover from this, I hope that I can maintain what I feel now, I don’t want to lose it.

“It’s so, so much larger than the me and life. It hasn’t got anything to do with a little green planet, a blue orb, it has to do with the enormity and the quickness and the suddenness of life and death. Oh my God.”

As celebrity endorsements go, Shatner’s flight and his post-landing comments were in a class by themselves and no doubt music to the ears of Bezos as he battles Branson and Virgin Galactic for market share in the growing commercial space marketplace

Branson won the commercial sub-orbital space race in 2018 when his company launched its first piloted test flight above 50 miles, the boundary of space recognized by NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration.

While Branson’s July 11 sub-orbital hop was Virgin’s fourth carrying pilots, it was the first with a full six-person crew and the first with the company owner on board.

Branson announced his flight after Bezos had already selected his July 20 launch date, upstaging the Amazon founder and grabbing headlines in the battle to sell a product — spaceflight — as a for-profit enterprise.

“I truly believe that space belongs to all of us,” Branson said before his flight. “After more than 16 years of research, engineering and testing, Virgin Galactic stands at the vanguard of a new commercial space industry, which is set to open space to humankind and change the world for good.”

New Shepard’s path to space

Unlike Virgin’s VSS Unity spaceplane, which is launched from a carrier jet and glides to a runway landing after a brief visit to the lower edge of space, Blue Origin’s New Shepard is a much more traditional rocket and capsule.

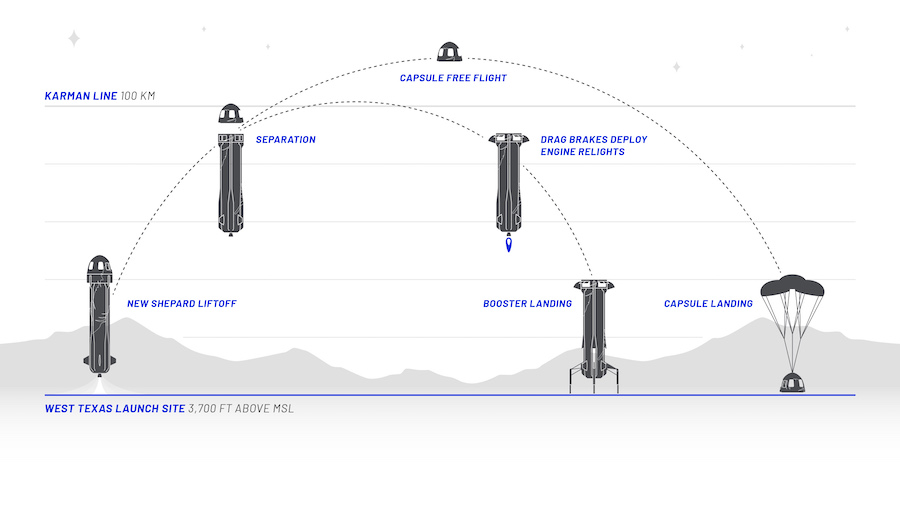

In a little more than two minutes, the single-stage booster propels the capsule and its crew straight up to an altitude of about 32 miles and a velocity of some 2,200 mph before main engine shutdown.

Less than 30 seconds later, at an altitude of about 45 miles, the crew capsule is released to fly on its own.

While the reusable booster heads back to landing on a nearby pad, the crew capsule continues upward on an unpowered, ballistic trajectory, reaching a maximum altitude of just above 62 miles three-and-a-half minutes after takeoff.

The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), an international body based in Switzerland that certifies aerospace records, considers an altitude of 100 kilometers, or 62 miles, as the dividing line between the discernible atmosphere and space.

NASA and the FAA say 50 miles is the point where wings and aerosurfaces no longer have any effect on a vehicle’s motion and thus defines the starting point of “space.” Virgin Galactic uses that guideline while Blue Origin meets both standards.

In any case, approaching the top of the trajectory, Churchley, Strahan and their crewmates will experience about three minutes of weightlessness, enough time to unstrap and float about the cabin while enjoying spectacular views of Earth through six windows more than a three feet tall and nearly two-and-a-half feet wide.

Plunging back into the lower atmosphere, the capsule will rapidly decelerate, briefly subjecting the passengers to more than five times the normal force of gravity, before three large parachutes unfurl, lowering the craft to a gentle touchdown a few miles from the launch pad.

From liftoff to landing: about 10 minutes. Virgin passengers enjoy a longer flight, about 90 minutes from carrier jet takeoff to spaceplane landing, but the time spent “in space” is roughly the same.