A ship carrying the $10 billion James Webb Space Telescope left a port in Southern California last weekend to begin a nearly two-week journey to Kourou, French Guiana, where it will begin final preparations for launch Dec. 18 on a European Ariane 5 rocket.

“The James Webb Space Telescope is finished,” said Paul Hertz, head of NASA’s astrophysics division, in a presentation to the Astronomy and Astrophysics Advisory Committee earlier this week. “We’ve stopped working on it. It’s on the way to the launch pad for a launch on Dec. 18.”

Eric Smith, NASA’s program scientist for the Webb telescope, confirmed Wednesday the observatory has departed the United States after completing final testing at a Northrop Grumman facility in Redondo Beach, California.

“We are in transit to Kourou, having left the continental United States now,” Smith said in the advisory committee meeting.

NASA is keeping specific schedule details about the observatory’s journey under wraps for security reasons. The vessel carrying the Webb telescope will traverse the Panama Canal to cross from the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea, then complete the voyage to Kourou, French Guiana.

Smith said mission managers have 13 days of schedule margin to have Webb ready for launch Dec. 18. Liftoff is scheduled in the mid-morning, local time, in French Guiana.

Besides the hands-on work on Webb itself, Smith said NASA and ESA will closely watch the launch of an Ariane 5 rocket next month with an SES commercial communications satellite and a French military spacecraft. Webb’s launch date of Dec. 18 hinges a successful outcome of that mission.

The shipment of the Webb telescope to French Guiana follows a series of tests at Northrop Grumman to ensure the spacecraft can withstand the rigors of launch. The testing subjected the observatory to the vibrations and sound energy it will see inside the payload shroud of its Ariane 5 launcher.

Then engineers performed final tests to unfurl the observatory’s mirrors and sunshield, checking that the deployment mechanisms are ready to go. It was the last time Webb’s components will deploy into flight configuration before liftoff.

With those tests complete, crews at Northrop Grumman folded up the observatory and put it in a climate-controlled shipping container for the trip to French Guiana.

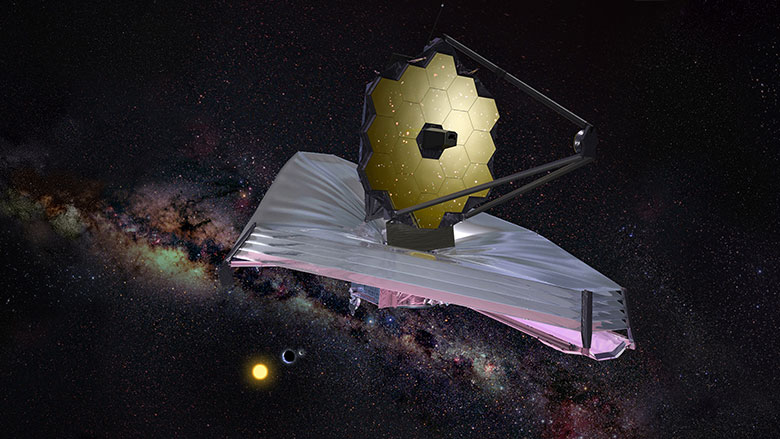

Webb, a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, is a joint project between NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency. The observatory’s total cost is near $10 billion, making Webb the most expensive and complex science mission ever launched.

Design work on Webb began in the 1990s, and NASA awarded a contract to Northrop Grumman in 2002 to oversee construction of the observatory. With the shipment of Webb to Kourou, the project is in the home stretch before launch.

One of ESA’s contributions is the Ariane 5 rocket that will launch Webb toward its operating post nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

After launch, the observatory will begin a make-or-break sequence of deployments to extend its solar array, high-gain antenna, and mirror segments. Webb also has a five-layer sunshield to shade its mirrors, detectors and science instruments, keeping the telescope colder than minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 223 degrees Celsius.

Made of aluminum-coated Kapton, each sunshield layer is as thin as a human hair. The sunshade will expand to the size of a tennis court once Webb is in space.

The observatory’s infrared instruments will peer into the oldest, most distant reaches of the universe to study some of the first stars and galaxies that formed after the Big Bang more than 13.5 billion years ago.

Astronomers will also use Webb to look at how galaxies form and evolve, to study the birth of stars, and to learn more about the atmospheres of planets that may be hospitable for life outside our solar system.

Once Webb arrives at the Guiana Space Center, the Ariane 5 launch site in South America, teams will unpack the observatory from its shipping crate and begin “aliveness” and systems tests to make sure the spacecraft weathered the intercontinental journey from California.

Ground support equipment for Webb has already arrived at the Guiana Space Center.

“They’re beginning to assemble the HEPA filter walls,” Smith said. “That will give us an extra clean environment in the processing facilities. So folks have been on the ground at Kourou now for about a week for us setting up.”

Controllers at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore will take command of Webb after it separates from the Ariane 5 rocket about a half-hour after liftoff. Smith said the control team in Baltimore will conduct a final readiness exercise for Webb’s launch and commissioning next month.

“This will be Launch Readiness Exercise No. 6,” Smith said. “Through all of them, all aspects observatory deployments and commissioning will have been exercised.”

Other work planned at the Guiana Space Center includes mounting of Webb to its payload adapter, the structure that will attach it to the top of the Ariane 5 rocket. Then technicians will load toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants into the spacecraft.

The liquid propellants will feed Webb’s maneuvering thrusters to keep the spacecraft on course toward its destination a million miles from Earth, and maintain its trajectory around the second Lagrange point, or L2. In orbit around L2, the balance of the gravitational pull from the Earth and sun will keep Webb in a relatively stable region, giving the observatory unimpeded views of deep space.

Ground crews in French Guiana will next move the spacecraft to the Ariane 5 rocket’s final assembly building for stacking on top of the launcher. The fully-assembled Ariane 5 will roll out to the launch pad at the Guiana Space Center one day before liftoff.

Webb’s post-launch commissioning will last around six months, Smith said. That time includes all the observatory deployments, the cruise to Webb’s observing location beyond the moon’s orbit, and the gradual chill down of the telescope’s infrared detectors to cryogenic temperatures.

The super-cold conditions will allow the telescope’s instruments to be sensitive enough to detect the faint ancient light from some of the universe’s oldest objects.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.