STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

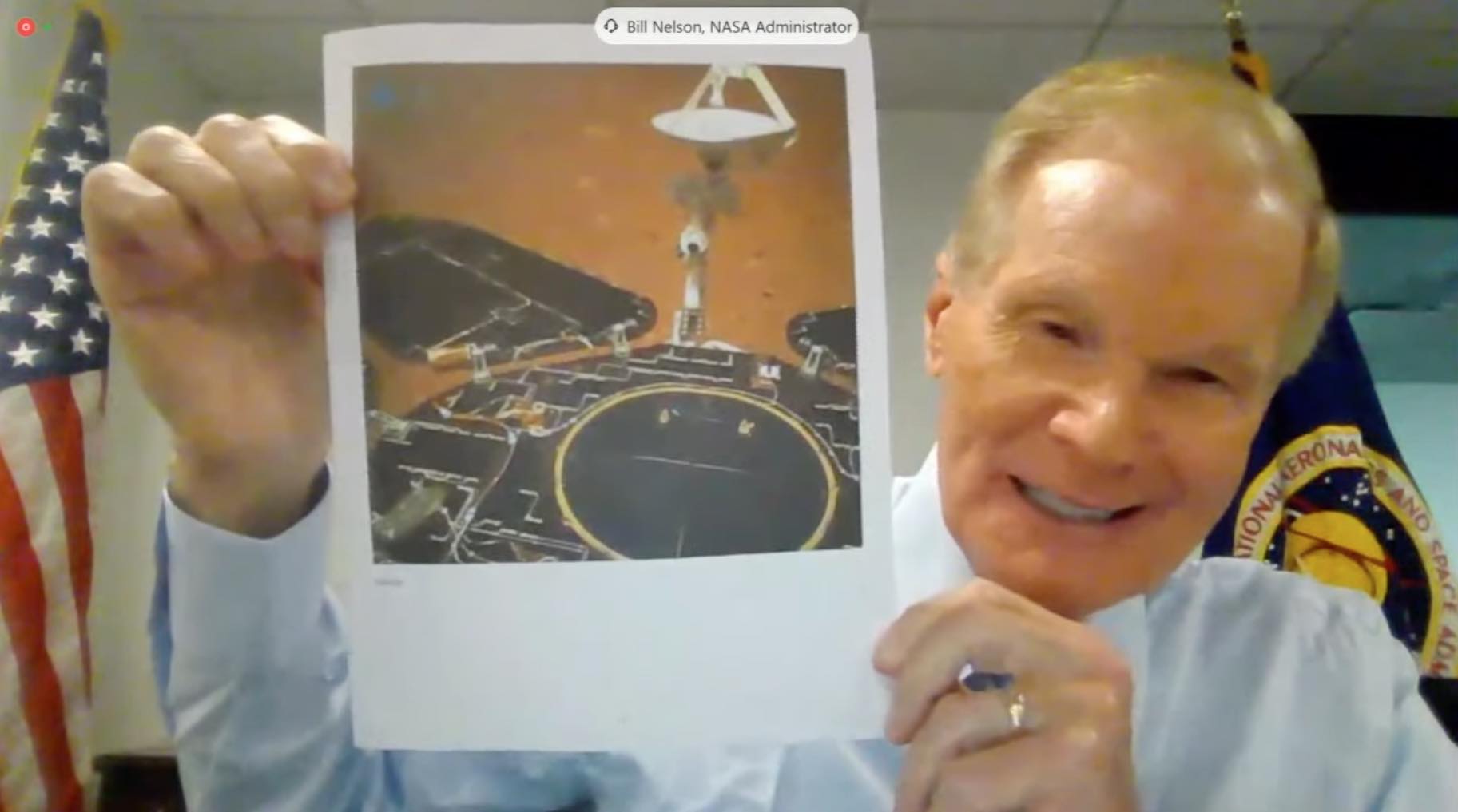

Holding up a photo taken by China’s new Mars lander, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson warned Congress Wednesday that his agency faces increasingly stiff competition on the high frontier and that sustained funding for a new moon lander, infrastructure upgrades and other critical programs is vital for America’s space program.

In his first congressional appearance since confirmation in the Senate, Nelson, a former lawmaker who flew aboard a space shuttle in 1986, told a House appropriations subcommittee that China plans to send multiple landers to the south pole of the moon in the not-too-distant future, the same area NASA is targeting in its Artemis program.

And the moon isn’t the only arena where NASA faces competition from China’s increasingly capable space program.

“I want you to see this photograph,” he said in the virtual hearing, holding up a photograph taken this week by China’s Zhurong rover, which successfully landed on Mars last week. “This is the Chinese rover that has now landed on Mars and has sent back this picture.”

The successful Mars landing followed the April launch of the first module of a new Chinese space station. Nelson said China is gearing up for multiple missions to the moon’s south pole, leading up to a “flyby and a lunar lander in the decade of the 2020s.”

“I think that’s now adding a new element as to whether or not we want to get serious and get a lot of activity going in landing humans back on surface of the moon,” he said.

He was speaking to a sympathetic audience.

“China’s dramatic progress with moon and Mars robotic elements, plus their space station elements, means that we cannot lose focus or momentum in developing our own programs,” said Rep. Robert Aderholt, R-Alabama, whose district includes parts of Huntsville and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

The hearing was called to discuss the Biden administration’s preliminary, or “skinny,” budget for fiscal 2022, which includes $24.7 billion for NASA, an increase of 6 percent above current funding levels.

NASA’s most ambitious program — Artemis — will consume a large fraction of the agency’s budget through the rest of the decade. The program is built around the gargantuan new Boeing-managed Space Launch System rocket, which will propel four-person astronaut crews to the moon aboard Lockheed Martin-built Orion capsules.

After braking into orbit, the astronauts will board a waiting lander and head for touchdown near the moon’s south pole where ice is believed to exist in ultra-cold, permanently shadowed craters. If ice is, in fact, present, future astronauts may be able to break it down to provide water, air and rocket propellants.

The SLS rocket is being assembled at the Kennedy Space Center for a maiden flight late this year to boost an unpiloted Orion capsule on a long looping trip around the moon. A piloted flight is planned in the 2023 timeframe followed one to two years later by what NASA bills as a mission to land the first woman and the next man to walk on the moon.

But that assumes a new lunar lander is available. Earlier this year, SpaceX won a $2.9 billion contract for the initial lander mission, beating out higher bids from a “National Team” led by Blue Origin, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, and Huntsville-based Dynetics.

Just like it did for commercial resupply missions and crew ferry flights to the International Space Station, NASA originally planned to select two winners. The goal was to ensure competition for multiple Artemis moon landings after the initial flight and provide redundancy in case of problems that might affect one company buy not the other.

But Congress only appropriated a quarter of the requested HLS funding, and NASA ultimately awarded a single contract to SpaceX on April 16.

Blue Origin and Dynetics promptly challenged the award, citing a variety of alleged improprieties and claiming NASA did not give them an opportunity to revise their bids when it became apparent the agency would not receive the requested funding.

The Government Accountability Office is reviewing the protest, forcing NASA to stop work on the lander contract until the issue is resolved.

“With China’s progress, and the lack of U.S. government ownership of the lander, it is unacceptable for the fate of the U.S. access to cislunar space to be in the hands of only one company,” said Aderholt. “I will have to admit that I have concerns about the process and how it was used to make a single award.”

Nelson told the panel he is committed to competition.

“But this is where you all become extremely important partners in this whole competition, because if we are going to the surface of the moon with humans, it is going to cost some money,” he said.

In the fiscal 2021 budget, he said, NASA asked for $3.4 billion to fund lander development but only $850 million was appropriated.

“They just simply didn’t have enough to keep going forward (with) more than one lander,” Nelson said. “If the bid protest is successful … then everything starts over, and you do (another) competition. If it is not successful … what’s been done is done.”

If so, there will still be opportunities for competitors, he said “because this first competition was only as a demonstrator to show that you can land and bring humans safely back home. There are many additional landings that are planned for on the moon.”

He said Congress could help by adding $5.4 billion to a jobs bill to help fund lander development and infrastructure upgrades to replace or repair aging NASA facilities. Such funding also could help pay for development of the spacesuits moon walkers will need and development of new propulsion technology to shorten the time needed for voyages to Mars.