Relativity Space, a small launch startup aiming to fly its orbital rocket from Cape Canaveral for the first time next year, announced Wednesday it has signed a contract with Iridium for up to six launches of the company’s spare communications satellites.

Relativity also announced it plans to develop a second launch pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base on California’s Central Coast to allow for missions to polar orbits, including the launches carrying Iridium satellites.

The dual announcements signal a big step for Relativity, which obtained $140 million in funding last year from venture capital funds and capital investors. Coupled with $45 million from earlier funding rounds, that’s enough to carry the company through the first flight of its Terran 1 launcher from Cape Canaveral toward the end of 2021, according to Tim Ellis, Relativity’s co-founder and CEO.

Based in Los Angeles, Relativity plans to move into a new headquarters and high production rate factory later this year in Long Beach, near the headquarters of two other small satellite launch companies — Virgin Orbit and Rocket Lab.

Ellis said Relativity’s rocket development program has encountered some delays due to the coronavirus pandemic, which shut down access to NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi to non-essential personnel. Relativity is testing components of the Terran 1 rocket’s Aeon engine at Stennis, and the pandemic’s impacts there will likely push back the rocket’s inaugural launch by a month or two, Ellis said.

But production of structural components for ground testing continues in Los Angeles. Relativity says 95 percent of the Terran 1 rocket will be 3D-printed, and Ellis said the company can still operate printers with just one person inside each building.

“We’ve actually seen 3D printing, simpler supply chains, and the more autonomous nature of the technology help us remain productive during this,” Ellis said.

Although Relativity’s Terran 1 rocket has not flown yet, Iridium officials said they were satisfied with Relativity’s technical progress.

“I think we like what we see,” said Suzi McBride, Iridium’s chief operations officer. “They’re building a strong team. They’ve got good development. They’ve done some first article testing and things that give us some confidence that they’re on the right trajectory.

“They clearly have a long way to go still, and they’re in process with that, but they seem to be a good partnership,” McBride said. “We can work with them and ensure that as they develop their vehicle, they’re always considering and making sure that Iridium fits and works with it.

“Our satellites are built at this point, so we need to have partners that can handle the satellites as built without making a lot of changes,” McBride said. “That’s really important for us, so getting in at this ground level with them is a great strategic partnership to keep us aligned as they move their development forward.”

Standing around 115 feet (35 meters) tall, the Terran 1 rocket can carry up to 2,755 pounds, or 1,250 kilograms, of cargo to a low-altitude orbit. That’s significantly more than other commercial small satellite launchers, such as Rocket Lab’s Electron vehicle.

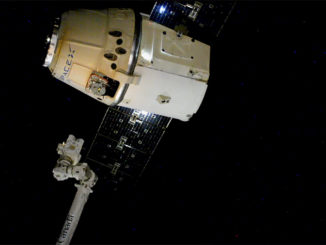

Iridium launched 75 of its new-generation Iridium NEXT voice and data relay satellites on a series of eight SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket flights from early 2017 through early 2019. Thales Alenia Space and Northrop Grumman, Iridium’s satellite production contractors, built 81 Iridium NEXT spacecraft in a factory in Gilbert, Arizona.

Iridium’s constellation includes 66 operational satellites spread across six orbital planes, providing global coverage for military, aviation, maritime, and other customers. There are nine spare Iridium satellites currently in orbit.

The Iridium NEXT satellites replaced Iridium’s previous fleet of communications satellites launched in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Most of the older satellites were guided to re-enter the atmosphere and burn up as the Iridium NEXT satellites came online, but some remain in orbit.

All 75 Iridium NEXT spacecraft currently in orbit are healthy, but McBride said Iridium wants to have a launch provider ready to launch the spare satellites if needed.

Each Iridium NEXT satellite weighs around 1,896 pounds (860 kilograms) fully fueled for launch. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 can launch up to 10 Iridium NEXT satellites on single flight, but Iridium prefers to launch the spare satellites one-at-a-time, allowing the rockets to aim for a specific orbital plane to replace a failed spacecraft.

File photo of an Iridium Next satellite. Credit: Thales Alenia Space

File photo of an Iridium Next satellite. Credit: Thales Alenia Space

“In operations, ideally you don’t want to have to launch if you don’t have to,” McBride said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “Relativity was kind of in our sweet spot because of performance and size. We’re kind of a larger satellite for the smallsat (launch capabilities, so a lot of the other emerging small satellite launch vehicles really are not capable of our size.”

McBride declined to say how much Iridium is paying Relativity per launch, but she said Iridium got a “good price” that was lower then Relativity’s advertised launch price of $12 million per Terran 1 mission.

McBride said Iridium’s contract with Relativity allows for flexibility to launch the six satellites as needed between 2023 and 2030.

“It is a firm contract, but there’s a lot of flexibility and key terms built in for us,” McBride told Spaceflight Now. “Obviously, Relativity has a newer vehicle being developed still, so we ensure that our contract has all the right provisions to make sure that we are protected and give us time to watch them develop.”

“We don’t need them right now,” she said. “What this is bout is putting another capability into our toolbox … What’s imp for us is we only want to launch when we need to launch spares. If we launch them now, we put them up early and don’t know where we need them. So having this capability was something unique that Relativity offers to be able to launch one at a time. They have a very short call-up time given their technology with 3D printing. That allows more flexibility for us to really kind of wait and see.”

Relativity says its large-scale robotic 3D printing technology enables launches within months, instead of years.

The Iridium NEXT satellites are in storage at Northrop Grumman’s spacecraft manufacturing facility near Phoenix.

Iridium is no stranger to committing to a start-up launch provider. The company signed a contract in 2010 to launch the bulk of its new-generation satellite constellation on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets, just weeks after the Falcon 9 launched for the first time.

The first batch of Iridium NEXT satellites launched on a Falcon 9 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in January 2017.

“We’re not in a hurry right now, which is a great place to be,” McBride said. “We’re going to just kind of watch them develop and be part of their team and partner with them as they continue their development program. And we will continue to watch our constellation health and needs and base our decisions on what we’re seeing with our constellation over time. So we’ll decide when, and how many, and how to get those launched as our situation changes.”

Ellis, Relativity’s co-founder and CEO, said Iridium will be the anchor customer for the new Terran 1 launch site at Vandenberg. Iridium is the fifth customer to sign up for launches with Relativity, following agreements to launch satellites for Telesat’s low Earth orbit communications fleet, rideshare launch arrangements with Spaceflight, and other contracts.

The launch contract with Iridium was made possible by a decision last year by Relativity to expand the payload envelope on the Terran 1 rocket. The Terran 1’s payload fairing will have a diameter of nearly 10 feet, or about 3 meters, roughly 3 feet wider than the earlier design.

“The only companies that can do dedicated launches of that size payload — like a single Iridium satellite — are much closer to the Vega from Arianespace and PSLV in India, and we’re building an all-U.S.-based, built, designed, flown and funded version of that,” Ellis said. “We think that’s going to be important not just for commercial companies, but also the government in the future.”

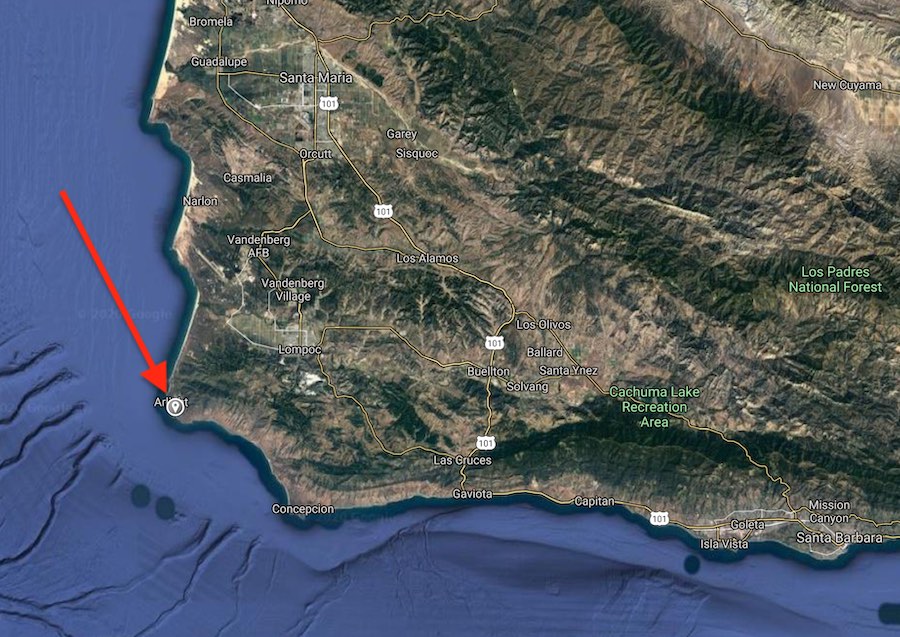

Relativity’s launch site at Vandenberg will be located near the Building 330 facility on Vandenberg’s South Base, just south of of the SLC-6 launch site currently used by United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4-Heavy rocket.

Originally developed to support the Air Force’s plans to launch space shuttles from Vandenberg, the Building 330 site is currently vacant and available for development. Ellis said the Space Force’s 30th Space Wing, which oversees operations at Vandenberg, selected the Building 330 site for Relativity.

Relativity has obtained a “right of entry” approval for Building 330, and the launch site will now undergo an environmental review progress.

“That will culminate in a site license that will allow us to do all the heavy construction to build the site up,” Ellis said.

The launch site at Vandenberg will give Relativity’s rockets access to reach north-south polar and sun-synchronous orbits. Launches from Cape Canaveral will deliver payloads into lower inclination orbits, medium-altitude orbits, and geostationary orbits, according to Ellis.

Relativity chose to launch from Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg because the company’s prospective customers — commercial satellite operators, the U.S. military and NASA — are “used to launching from those facilities,” Ellis said. “There’s a lot of deep expertise there in how to have robust government and commercial operations.”

While Iridium does not plan to launch its spare satellites before 2023, Relativity says its Vandenberg launch site could be operational before then.

“Quite a bit of the market for these small to medium payloads is in polar and sun-synchronous orbit, so that was actually really critical to open up the rest of the market, culminating with Iridium as the first announced anchor customer,” Ellis said.

The Terran 1 launch pad’s location at the far southern edge of Vandenberg’s Pacific coastline comes with some advantages.

“It’s on the far south side of the base, so since all Vandenberg launches are southerly, that’s actually a prime location because we don’t overfly any of the major existing launch sites,” Ellis said. “Since we don’t overfly them, we believe we’re going to have far fewer scheduling conflicts and more launch availability.”

Building 330 is “an old processing facility, so we are going to be removing that and building more of our own launch tower, lightning protection system, payload processing, that type of infrastructure,” Ellis said.

Relativity is building its Cape Canaveral launch facility at Launch Complex 16 first, aiming for a first flight of the Terran 1 there in late 2021. The company announced in January 2019 that it obtained right of entry approval for Launch Complex 16 from the 45th Space Wing at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

Ellis said the public comment period for the environmental review at Launch Complex 16 recently completed, and he expects a site license to be issued to Relativity there “imminently.”

Meanwhile, demolition of some infrastructure at Launch Complex 16 — a long-dormant facility once used for Titan and Pershing missile tests — has gotten underway recently, Ellis said.

“We started tearing down some of the concrete,” he said. “All of the long-lead items (for the launch pad) are on order, the lightning protection system, water tanks, propellant tanks, all of that stuff is coming. The design is done, and once we get the site license in hand, we’re going to really double down on the construction efforts, and I think we’ll make progress very quickly.

“We’re building a launch vehicle integration horizontal hangar,” he said. The (rocket) will just roll straight out onto the top of the pad with a horizontal transporter erector. All of that stuff is in design finalization now and will come together in real hardware quite soon.”

More construction will be required to ready the Vandenberg site for launches, according to Ellis.

Relativity aims to have a fully-assembled Aeon engine ready for test-firings at Stennis before the end of this year. The methane-fueled Aeon engine produces about 23,000 pounds of thrust at sea level, and nine Aeons clustered on the Terran 1’s first stage will generate more than 200,000 pounds of thrust at liftoff.

A full-up test firing of a second stage, with a single Aeon engine, is planned at the Stennis Space Center in early 2021. The first fully integrated firing of all nine Aeon engines on a Terran 1 booster will occur on Relativity’s launch pad next year at Cape Canaveral, according to Ellis.

Ellis said Relativity — now with a staff of about 165 employees — has not encountered any major difficulties due to the economic downturn stemming from the coronavirus pandemic. Military officials have singled out the small satellite industry as a sector that could be susceptible to adverse impacts from the economic slump.

“We’ve seen more customer inquiries in-bound, and are working on more potential contracts than we ever have,” Ellis said. “Even with certain high-profile bankruptcies like OneWeb and Intelsat, which are unfortunate, we’ve seen no slowdown in the overall satellite market.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.