NASA has selected Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX to move forward with development of human-rated lunar landers, committing nearly $1 billion in funding for a range of moonship concepts that include a variant of SpaceX’s next-generation Starship vehicle, officials announced Thursday.

“These are three companies that we believe have a lot of capability that are going to enable us to get to the moon,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “Each one of them is very different. They have all proposed something very different and unique, which has a lot of value to us.”

Blue Origin, founded by Amazon president and CEO Jeff Bezos, is partnering with Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman to develop and build a crewed lander. Dynetics is collaborating with Sierra Nevada Corp. on its lunar lander concept.

NASA said Blue Origin’s contract is valued at $579 million, and Dynetics will receive $253 million for the 10-month contract base period. That money covers just the first phase of a multi-year lunar lander development effort that NASA predicts could cost $18.4 billion through the end of 2024.

Each commercial lander contractor team is expected to provide private funding to support lunar lander design and development.

The $135 million contract with SpaceX marks the most significant government investment to date in SpaceX’s Starship system, but Blue Origin and Dynetics won larger lunar lander contracts from NASA.

“Looking at the different (HLS) contractors, each one of them is very different,” Bridenstine said. “Some of them are likely to be more interested in going fast, others are more likely interested in creating the breakthrough technologies that are going to drive down cost and increase access.”

“SpaceX proposed the Starship,” Bridenstine said. “It’s obviously a very different solution set than any of the others. But it also could be absolutely game-changing. So we don’t want to discount it. We want to move forward. If they can have success, we want to enjoy that success with them.”

The development of a commercial human-rated lunar lander is expected to drive NASA’s schedule for returning astronauts to the moon. Last year, the Trump administration set a 2024 goal for the first lunar landing with astronauts since the last Apollo moon mission in December 1972.

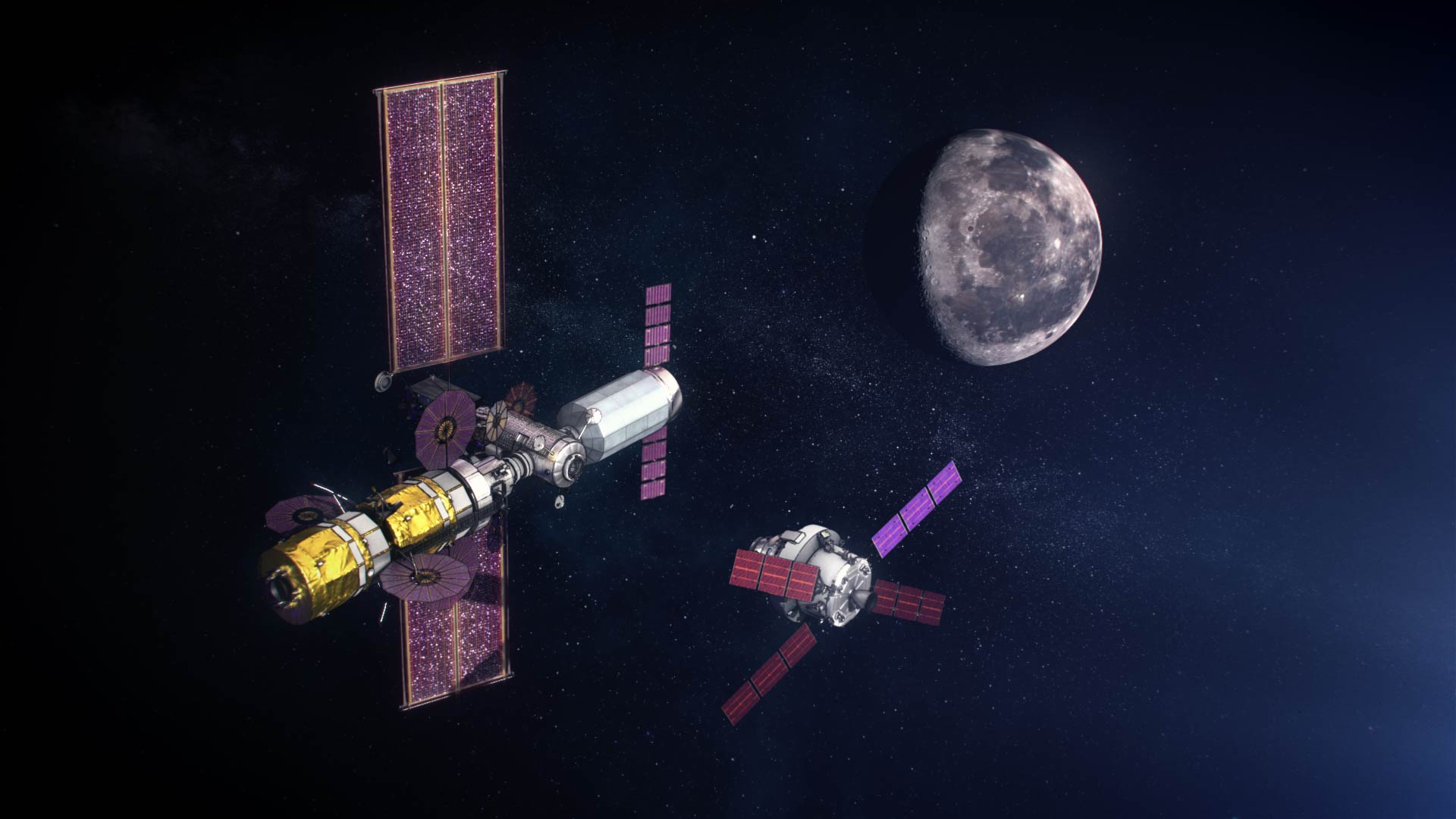

The program, named Artemis, includes the Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket and Orion crew capsule, and a mini-space station named the Gateway to be assembled in a distant, elliptical orbit around the moon.

Congress appropriated $600 million for the Human Landing System, or HLS, program in fiscal year 2020, short of the Trump administration’s $1 billion request. The White House requested more than $3.3 billion for the human-rated lander program in fiscal year 2021, which begins Oct. 1.

“We’ve selected the best of industry’s ideas to team with NASA,” said Doug Loverro, associate administrator of NASA’s human exploration and operations mission directorate. “This is really the last piece of the puzzle to go ahead and get us back to the moon. We’ve got all the other pieces in work already, and this is the last big piece. We are ready to move forward on this.

The three contractor teams will continue refining their Human Landing System concepts for the next 10 months before a “continuity review” next February. At that time, NASA could down-select to two HLS contractors, and pick one for the Artemis program’s first crewed lunar landing mission — known as Artemis 3 — before the end of 2024.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do over the next 10 months,” Loverro said. “We’ve got to go ahead and work with the contractors to define the right requirements for each of them, the right technical trades that enable one of those two important objectives — getting there fast and getting there sustainably — and to really get us pointed in the right direction.”

A key to NASA’s vision for a “sustainable” crew presence on or near the moon is the Gateway station. NASA officials originally hoped the Gateway would be in position near the moon in time for the Artemis 3 mission in 2024, allowing elements of the lunar lander to be assembled, or aggregated, at the Gateway before the arrival of astronauts on an Orion crew capsule.

Bridenstine told Spaceflight Now the Artemis 3 mission will no longer go through the Gateway, but NASA is not backing away from the program.

“When we think about a sustainable presence at the moon, we absolutely need a Gateway,” Bridenstine said. “The Gateway gives us the ability to reuse landers, over and over again, which drives down cost and it increases access. The Gateway gives us access to different orbits around the moon, so we can get to the north pole, the south pole, the equatorial regions, and everything in between.

“The Gateway is also transformable,” Bridenstine said. “We can use it eventually for our ship to Mars. The Gateway gives us the opportunity to do science, and it gives us a lot of credibility with our international partners, who are very interested in helping us build out the Gateway. I just want to emphasize … we are 100 percent committed to the Gateway.”

But the Trump administration’s goal to land astronauts on the moon by the end of 2024 has forced NASA to defer some work.

“It is also true that we’re 100 percent committed to getting to the moon as fast as possible,” Bridenstine said. “So anything that is not necessary, we intend to remove from that path for speed. So the first moon landing, we’re intending not to use the Gateway. We’re intending to basically take an Orion crew capsule and dock it to a Human Landing System that will be in orbit around the moon, and then go down to the surface of the moon.

“That means that we will not have the Gateway in place for the first landing on the surface of the moon,” he said. “The second time when we land humans on the moon, we absolutely want to have the Gateway in the mix because we need to land on the moon by 2024, and we need to have a sustainable presence by 2028.”

Boeing also submitted a proposal for NASA’s Human Landing System, but NASA ended up preferring bids from other contractor teams. NASA and government watchdog groups, such as the Government Accountability Office, have criticized Boeing’s performance on the Space Launch System, which launch Orion crew capsules with moon-bound astronauts.

The core stage of the Space Launch System is built by Boeing. Delays on the core stage have been largely responsible for delays in the first SLS test launch from 2017 until late 2021.

Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule, designed to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station, has also run into problems. The first unpiloted Starliner test flight failed to reach the space station in December, and Boeing plans to fly a previously-unplanned Starliner demonstration mission to the station without astronauts later this year before beginning crewed flights.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Human Lander System program, which is modeled on the public-private partnerships forged by NASA’s commercial cargo and crew development initiatives to transport supplies and astronauts to the International Space Station.

“Each company proposed a little bit different that they needed to do on their designs during the base period,” Loverro said. “They all proposed different amounts of money in order to go ahead and get that work done. The total amount that we awarded for all three of them together is about $967 million.”

For the first 10 months, Blue Origin’s team will get about 60 percent of the total funding amount.

“They’re all proposing a different amount of their own corporate investment within those figures as well,” Loverro said. “We felt that all the prices were reasonable for what the companies proposed to do.”

Bezos, Blue Origin’s founder, announced last year that Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman will build elements of the company’s human-rated lunar lander, and Draper will lead development of the lander’s avionics and guidance systems.

Bezos said Blue Origin has assembled a “national team” of aerospace contractors to develop, build and fly the three-stage spacecraft, which is based on Blue Origin’s previous work on the Blue Moon cargo landing system.

Northrop Grumman will supply a transfer stage to maneuver the lunar lander from a high orbit around the moon — where the Orion and Gateway will be located — to a lower altitude in preparation for landing. Blue Origin will oversee the development of a descent stage to perform a precision landing with the astronauts.

The descent stage will be powered by Blue Origin’s BE-7 engine, a deeply throttleable engine fed by cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

Lockheed Martin will build an ascent stage to boost the crew off the moon’s surface back toward the Orion spacecraft, which will be flying on its own for the Artemis 3 mission, or docked at the Gateway on subsequent flights. The ascent module could eventually be reused for multiple trips to the moon’s surface and back.

Elements of Blue Origin’s Integrated Lander Vehicle, or ILV, would launch on the company’s own New Glenn rocket and United Launch Alliance’s next-generation Vulcan rocket, according to NASA.

“For these initial contracts … given what the contractors proposed, both Blue Origin and Dynetics proposed solutions that could use Gateway or could go directly to Orion,” Loverro said. “SpaceX proposed a solution for this base period that they’re working on that would just go to Orion.”

Elements of lunar landing vehicles will launch separate from the SLS and Orion flight that will carry the astronauts. In the case of Blue Origin and Dynetics, the lander elements would depart Earth on commercial rockets and then be “aggregated” in lunar orbit to await the arrival of the Orion astronauts, according to Loverro.

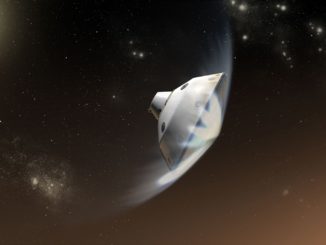

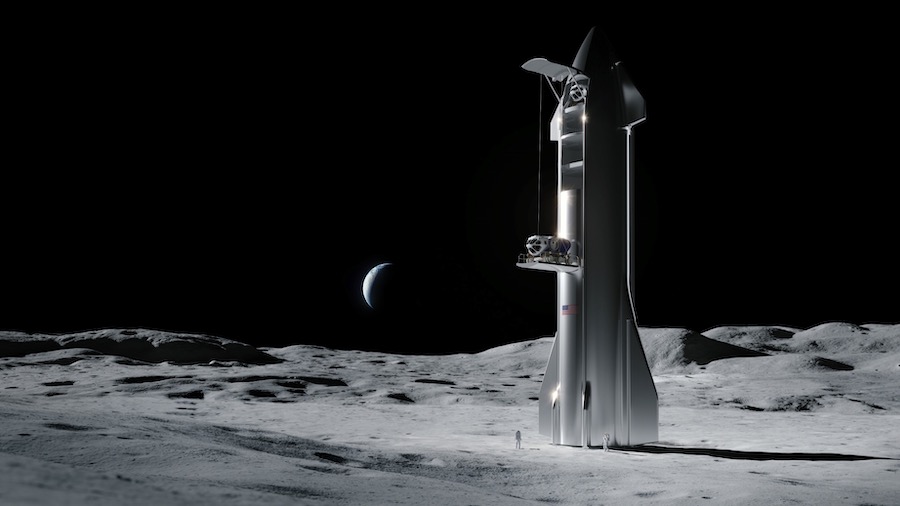

SpaceX’s reusable Starship will launch on top of a giant booster named the Super Heavy. The Starship vehicle, which serves as the upper stage on top of the Super Heavy booster, is designed to be refueled in space, enabling it to carry people and cargo to the moon, Mars and other solar system destinations.

“Utilizing parking orbit refueling, Starship is able to deliver unprecedented payload mass to a variety of Earth, cislunar, and interplanetary trajectories,” SpaceX wrote in a Starship user’s guide.

The user’s guide published by SpaceX indicates the vehicle can deliver more than 100 metric tons to the lunar surface, assuming in-orbit refueling for its methane-fueled Raptor engines. In that case, a separate craft would have to launch to deliver the fresh propellant to the Starship.

“SpaceX is more of an aggregation in Earth orbit,” Loverro said. “But they still have to meet up with Orion in lunar orbit.”

Several prototypes of the Starship vehicle have been built by SpaceX for testing at the company’s launch site in South Texas. After clearing a pressure test earlier this week, a Starship test vehicle could be test-fired in the coming days ahead of a 500-foot (150-meter) up-and-down hop test.

“I think Starship … will be flying quite soon,” said Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, earlier this week. “I think you’ll see regular flights within a couple of years, and that’s a very big rocket.”

By itself, the Starship vehicle will stand around 160 feet (50 meters) tall with a diameter of roughly 30 feet (9 meters), dwarfing the other human-rated lunar lander concepts. It will land and take off vertically, powered by Raptor engines each capable of generating nearly a half-million pounds of thrust at full power.

Last year, SpaceX signed an agreement with NASA to use the Starship to potentially carry robotic rovers, science experiments and other cargo to the moon’s surface. Now it could carry people.

While the Starship is designed as an all-purpose vehicle — capable of deploying satellites, science probes and crews — it would launch from Earth without a crew for NASA’s Artemis missions.

“In all architectures, the Orion capsule with the crew are launched on an SLS … and meet up with the Human Landing Systems at the moon,” Loverro said. “For the first mission, we’re doing that just directly between Orion and the Human Landing System. For the follow-on missions, we will then use Gateway as the intermediary.”

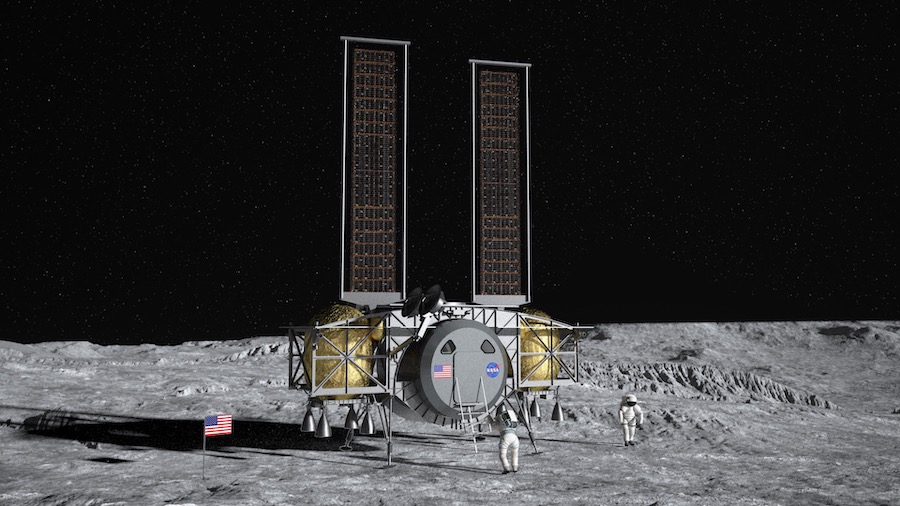

Dynetics has released little information about its proposed lunar lander, which would be developed in partnership with Sierra Nevada Corp.

The Dynetics Human Landing System would launch as a single structure providing ascent and descent capabilities, according to NASA. It would lift off from Earth on ULA’s Vulcan rocket.

Based in Alabama, Dynetics released an artist’s illustration of its human-rated lander in January that appears to show a large pressurized compartment, two large propellant tanks and power-generating solar panels extending vertically from spacecraft on the lunar surface.

A Dynetics spokesperson said in January that the company “put together a very impressive team of experienced small and mid-sized companies” for the HLS proposal.

Bridenstine said NASA hopes to move forward with all three landers after the continuity review next year. But it depends on the budget Congress appropriates for the program.

“We are hopeful that we can go forward with all three,” Bridenstine said. “It doesn’t mean that we will, but I think that each one of them is so unique and different, that we want to see what are the best capabilities that each of these companies bring to the table that we can take advantage of. That’s what this base period is really all about.

“If we did down-select, we would probably down-select to two,” Bridenstine said. “We wouldn’t probably go below two. That’s because there’s a difference between going fast and going sustainably, and a lot of these different companies have different solution sets for achieving each of those requirements.”

Loverro said NASA wants to evaluate how each lander concept evolves before picking a final design.

“We definitely want to keep as many companies in the mix as we can,” Loverro said. “We know that likely we will begin to point at different objectives, or different approaches, because the approaches are so different. That’s the advantage of trying to keep as many of them. We can both make sure that we are focused on both the fast objectives and the sustainable objectives, and at the same time allow multiple approaches for those objectives.

“Clearly, we’d love to go ahead and keep three on-board, but the budget will probably require that we go ahead and move to fewer contractors,” Loverro said. “Two is probably the least that we’ll get to. We need to keep competition going. Obviously, that’s critically important as well. And we need to make sure that we are able to focus each contractor on the objectives that we believe are most important for them.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.