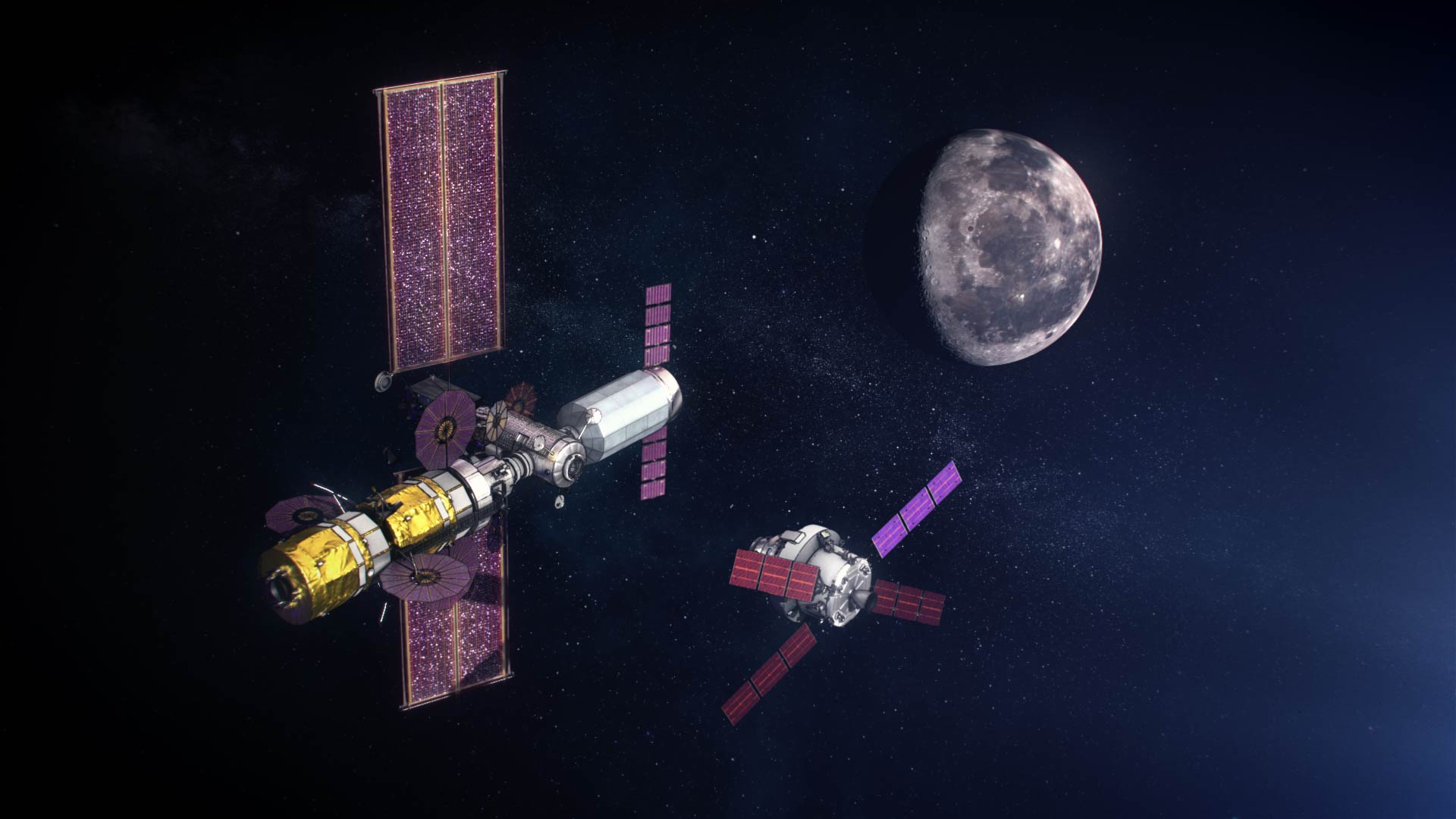

NASA has selected SpaceX to deliver supplies to the planned Gateway mini-space station in lunar orbit using a new version of the Dragon cargo vehicle launched atop Falcon Heavy rockets.

SpaceX is guaranteed a minimum of two supply missions under the Gateway Logistics Services contract. The cost of each SpaceX cargo mission was not disclosed by NASA.

The deal gives SpaceX its first major role in NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to land astronauts on the moon before the end of 2024. NASA envisions the Gateway as a waypoint for astronauts traveling to the moon, providing a hub for docking of Orion crew capsules, lunar landers, and research and logistics modules.

SpaceX will use a spacecraft named the Dragon XL to carry pressurized and unpressurized cargo, experiments and other supplies to the Gateway, which will be assembled in an elliptical, or egg-shaped, orbit around the moon. The equipment delivered by SpaceX’s Dragon XL missions could include sample collection materials, spacesuits and other items astronauts may need on the Gateway and on the moon’s surface, according to NASA.

The Dragon XL missions will launch on SpaceX Falcon Heavy rockets from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The first logistics mission to the Gateway is expected to launch as early as 2024, but could be delayed as NASA managers re-evaluate the Gateway’s role in the Artemis program.

“This contract award is another critical piece of our plan to return to the moon sustainably,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “The Gateway is the cornerstone of the long-term Artemis architecture and this deep space commercial cargo capability integrates yet another American industry partner into our plans for human exploration at the Moon in preparation for a future mission to Mars.”

The Dragon XL resupply spacecraft will stay at the Gateway for six to 12 months at a time, when research payloads inside and outside the cargo vessel could be operated remotely, even when crews are not present. It can carry more than 5 metric tons, or 11,000 pounds, of cargo to the Gateway, according to SpaceX.

SpaceX is building off the company’s Dragon 2 spacecraft designed to ferry crew and cargo to the International Space Station. Unlike the Dragon 2, which flies without an aerodynamic shroud on top of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, the Dragon XL will lift off inside a payload fairing on the company’s bigger Falcon Heavy launcher, according to Dan Hartman, NASA’s Gateway program manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“Returning to the moon and supporting future space exploration requires affordable delivery of significant amounts of cargo,” said Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and chief operating officer, in a statement. “Through our partnership with NASA, SpaceX has been delivering scientific research and critical supplies to the International Space Station since 2012, and we are honored to continue the work beyond Earth’s orbit and carry Artemis cargo to Gateway.”

The Dragon XL will dock autonomously with the Gateway station, using docking and navigation equipment that fly on the Dragon 2 crew and cargo vehicles.

The Dragon XL will ferry equipment inside and outside the spacecraft. The SpaceX-built cargo carrier could eventually deliver a Canadian-built robotic arm to the Gateway, Hartman said.

Mark Wiese, deep space logistics manager at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, said the agency considered selecting more than one cargo transportation provider for the Gateway, but eventually settled on picking a single contractor. NASA could open up the Gateway Logistics Services contract to more companies in the future, but there is no specific timetable to do so, he said.

Each logistics transportation provider, including SpaceX, will be guaranteed at least two missions, but NASA can order more. The maximum cumulative value of all of NASA’s Gateway Logistics Services contracts will be $7 billion over a 15-year performance period.

In an interview with Spaceflight Now, Wiese said the initial cargo missions to the Gateway will deliver supplies to the station, but won’t return hardware or lunar samples to Earth. NASA could add a request for return capability in the future, he said.

“This is an exciting new chapter for human exploration,” Wiese said in a statement. “We are bringing the innovative thinking of commercial industry into our supply chain and helping ensure we’re able to support crews preparing for lunar surface expeditions by delivering the supplies they need ahead of time.”

Doug Loverro, the associate administrator for NASA’s human exploration and operations, said earlier this month that NASA is moving the Gateway out of the critical path for the planned 2024 moon landing. Loverro, who took over as head of NASA’s human spaceflight programs last year, said he wants to minimize risks in achieving the 2024 schedule.

The 2024 moon landing goal was set by the Trump administration last year. NASA was previously aiming to return astronauts to the lunar surface in 2028.

NASA officials have said for years that the Gateway is necessary to achieve a sustainable human presence at the moon. While Loverro said NASA is “anxious” to make the moon program sustainable over the long term, the accelerated schedule for a 2024 landing required agency officials to be more “scrupulous” in their planning.

Loverro said earlier this month that there was a “high possibility” of delays in the Gateway program, and he added that schedule slips in the Gateway could force the crewed lunar landing to miss the 2024 goal.

NASA plans to launch astronauts on Orion crew capsules atop the agency’s Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket, then rendezvous with a lunar lander in orbit around the moon. Under the previous architecture, elements of a commercially-built lunar lander would launch on multiple commercial rockets and rendezvous together for assembly at the Gateway, then astronauts on the arriving Orion spacecraft would float into the lander for descent to the moon’s surface.

While development of the Gateway continues, Loverro suggested it’s no longer up against a 2024 deadline for the Artemis 3 mission, the first flight to attempt a crewed lunar landing.

“By taking Gateway out of the critical path for a lunar landing in ’24, I believe what we have done is create a far batter Gateway program out of it,” Loverro said.

Space agencies in Europe, Canada, Japan and Russia have proposed elements to join the Gateway, all launching after 2024.

NASA’s most recent schedule for building the Gateway called for a launching the facility’s power and propulsion module, to be built by Maxar Technologies, on a commercial launch vehicle at the end of 2022. A pressurized habitation element built by Northrop Grumman would launch on another commercial rocket in late 2023, giving the Gateway a minimal capability to host astronauts on the Artemis 3 mission on the way to the lunar surface.

Lockheed Martin is prime contractor on the Orion crew capsule, and Boeing builds the core stage of the Space Launch System. Study contracts for a human-rated lunar lander are expected to be announced soon.

The logistics contract gives SpaceX its first stake in the Artemis program.

The first logistics mission to the Gateway was planned to launch in 2024, before the Artemis 3 mission. With NASA’s decision to take the Gateway out of the critical path for the Artemis 3 mission, the first logistics delivery could be delayed.

Hartman said the Gateway program is currently on track to be ready in time for a 2024 lunar landing mission.

“We certainly believe we can get ready for the 2024 mission if called up in that scenario, and if not, we can adjust accordingly,” Hartman told Spaceflight Now on Friday.

A formal update on NASA’s Artemis mission architecture is expected to be announced some time in April.

NASA says one standard logistics mission is anticipated before each SLS/Orion crewed mission to the Gateway. Once at full capacity, and with pre-staged supplies, the Gateway could accommodate crews for 30 to 60 days, according to Hartman.

“We’re making significant progress moving from our concept of the Gateway to reality,” Hartman said in a statement. “Bringing a logistics provider onboard ensures we can transport all the critical supplies we need for the Gateway and on the lunar surface to do research and technology demonstrations in space that we can’t do anywhere else. We also anticipate performing a variety of research on and within the logistics module.”

Contributions from international partners, such as a Canadian robotic arm and a European communications and refueling module, would not arrive at the Gateway until after the 2024 moon landing attempt.

The Gateway will not be continuously staffed like the International Space Station. Instead, crews will rotate to and from the Gateway for a few weeks at a time.

Even though the Gateway is off the critical path for the 2024 lunar landing, the Orion spacecraft on the Artemis 3 mission will still use a similar elliptical near rectilinear halo orbit around the moon. That’s because the Orion spacecraft’s propulsion system does not have the ability to insert the capsule into a low-altitude lunar orbit like that used on the Apollo missions.

The lunar lander’s propulsion system will carry the astronauts from the elliptical lunar orbit, to the moon’s surface, and back to the Orion spacecraft.

Loverro said NASA remains committed to the Gateway program for lunar missions later in the 2020s, just not in 2024. He said the decision to remove the Gateway from the scope of the Artemis 3 mission will help NASA to keep from cutting technologies and capabilities to keep the program on track for the 2024 lunar landing.

“I do fundamentally believe you cannot do sustainable presence on the moon without Gateway,” Loverro said March 13. “You need an assembly point in the low gravity well of a near rectilinear halo orbit. You need an assembly place to go ahead and bring down the equipment that will be necessary for extended lunar durations.”

“So there’s no question that Gateway is part of that plan, and I think what we’re doing with Gateway makes sure that it does not get threatened by future cuts — or future budget overruns, more likely — on human landers, or Space Launch Systems, and Orion capsules, and those kind of things,” Loverro said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.