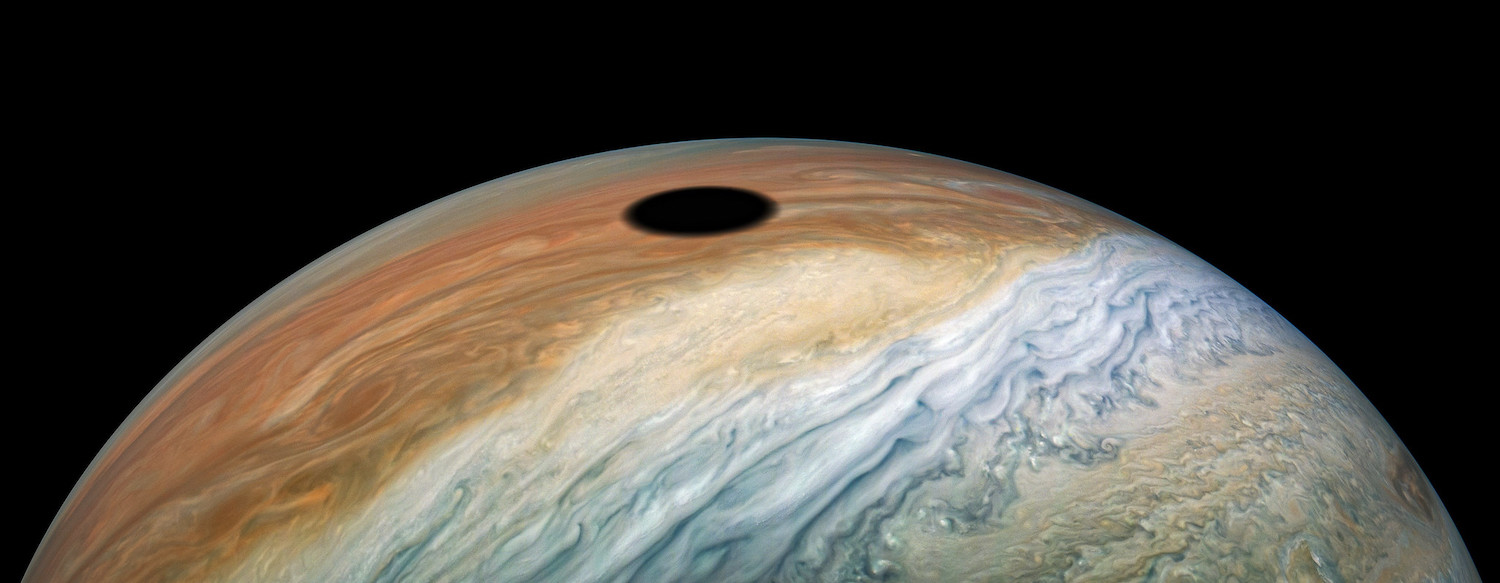

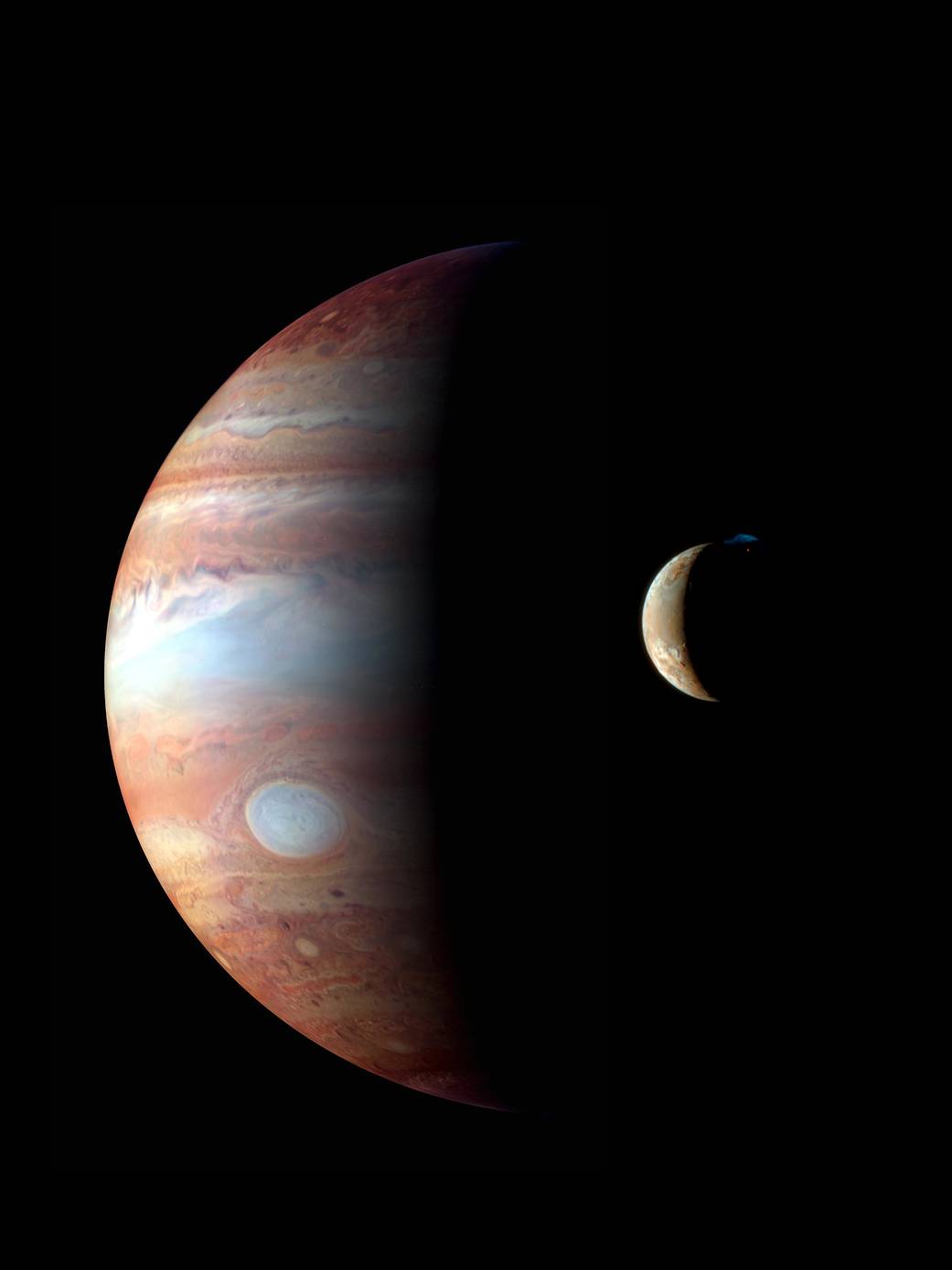

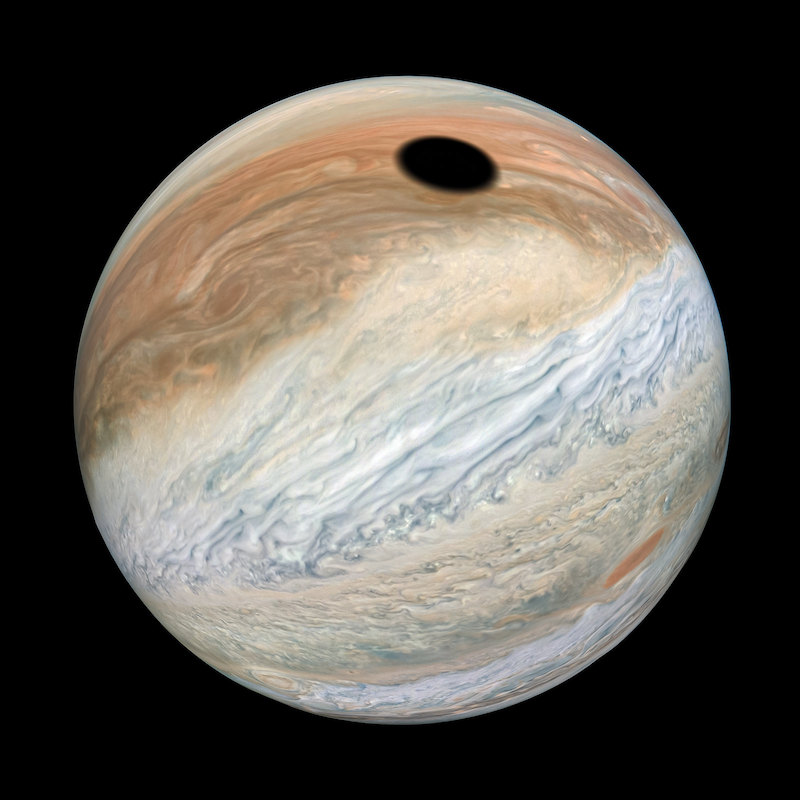

Fresh images from NASA’s Juno spacecraft show an ethereal shadow cast by Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io on the planet’s swirling cloud tops.

The JunoCam imager captured views of Io’s distinct shadow on Jupiter during its most recent passage near the giant planet, and skilled amateur image analysts immediately set to work processing the data into dazzling renderings showing a black circle amid Jupiter’s churning clouds.

Juno spotted the eclipse during a Sept. 12 encounter near Jupiter, the 22nd such flyby since arriving in orbit around the solar system’s largest planet on July 4, 2016. The spacecraft carries instruments to study Jupiter’s internal structure and weather, along with sensors to measure and map the planet’s strong magnetic field and gravity.

Io is the most volcanically active object in the solar system. Scientists have found hundreds of volcanoes on Io, many of them launching fountains of lava and gas hundreds of miles above the moon’s surface.

The volcanoes are caused by the immense pull of gravity from Jupiter, coupled with the weaker influence of gravity from Jupiter’s moon Europa. The gravitational forces tug on Io’s interior, shifting the rocky material inside the moon and generating heat from friction.

The super-heated molten rock, or magma, erupts through numerous geyser-like volcanoes, generating prominent plumes that reach far above Io. Jupiter’s volcanic moon is also covered in lava lakes, and has a thin atmosphere of sulfur dioxide, a gas emitted by volcanic eruptions.

NASA’s Juno spacecraft is circling Jupiter in an elliptical 53-day orbit, with a low point positioned roughly 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers) above the planet’s cloud tops.

The Lockheed Martin-built spacecraft is healthy, and all its instruments are operational, said Scott Bolton, the Juno mission’s principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, during a presentation last month to NASA’s Outer Planets Assessment Group.

Juno’s instruments have peered beneath Jupiter’s clouds to study the planet’s internal weather patterns.

Data from Juno indicate Jupiter has a fuzzy, ill-defined core that is much bigger than anticipated. The discovery has led scientists to suggest an ancient collision between a young Jupiter and another giant protoplanet could explain Jupiter’s fuzzy center.

Juno has also imaged Jupiter’s auroras, and studied lightning in the planet’s hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

NASA has approved Juno’s mission to continue through July 2021, but Juno could keep operating later into the 2020s. Juno is up for a mission extension review in 2020.

Engineers were worried intense radiation around Jupiter could damage Juno’s electronics during repeated passages through the planet’s radiation belts. The spacecraft’s computer and other sensitive electronics are surrounded by a titanium compartment, or vault, to shield the components from radiation.

Officials say they see no signs of radiation damage to the spacecraft so far.

Juno was originally supposed to maneuver into a lower, 14-day orbit around Jupiter after arriving at the planet in 2016. But a problem with the craft’s main engine prevented the orbit change from happening.

The longer 53-day orbit requires more time for Juno to obtain the mission’s required science data. The Juno mission was originally scheduled to end in 2018 with a controlled destructive plunge into Jupiter’s atmosphere.

One benefit of the longer 53-day orbit is Juno receives a lower radiation dose, alleviating some of the concerns about radiation damage to the spacecraft’s electronics.

In its current orbit, the Juno spacecraft would pass through Jupiter’s shadow in November, robbing the orbiter of sunlight for its power-generating solar arrays. Ground teams plan to use the spacecraft’s reaction control system thrusters Sept. 30 for a burn to slightly adjust its trajectory around Jupiter to avoid the eclipse.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.