STORY WRITTEN FOR CBS NEWS & USED WITH PERMISSION

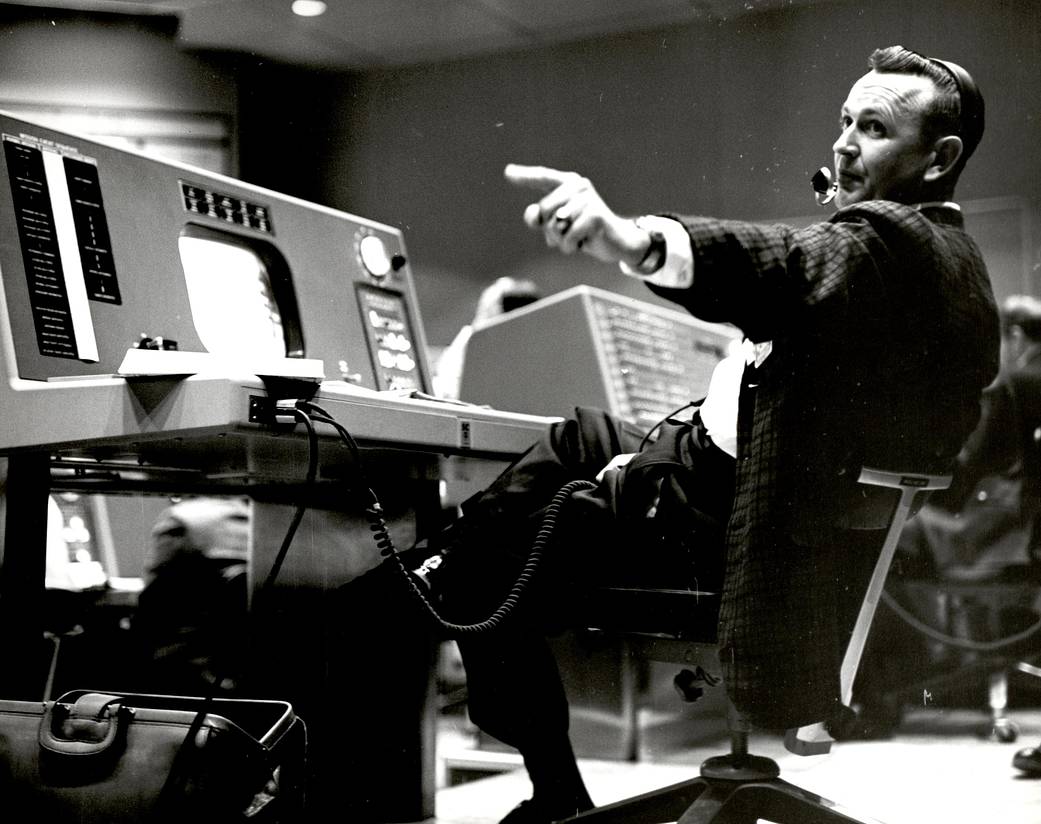

Former Johnson Space Center Director Christopher Columbus Kraft Jr., the man who created the iconic role of NASA flight director during the Mercury and Gemini programs and whose no-nonsense, uncompromising management style defined control room operations and discipline through the Apollo years and beyond, died Monday. He was 95.

“America has truly lost a national treasure today with the passing of one of NASA’s earliest pioneers – flight director Chris Kraft. We send our deepest condolences to the Kraft family,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine.

“Chris was flight director at some of the most iconic moments of space history, as humans first orbited the Earth and stepped outside of an orbiting spacecraft. … We stand on his shoulders as we reach deeper into the solar system, and he will always be with us on those journeys.”

A legendary figure at the Johnson Space Center and across the agency, Kraft once said he set up mission control to monitor spacecraft systems, interact with astronauts in space and to stand ready, spring-loaded to “figure out all the things that could go wrong and be prepared to to deal with them.”

“We called those mission rules,” he once told visitors to the Kennedy Space Center during a question-and-answer session. “And we wrote all the procedures, both for ourselves and the astronauts and called those malfunction procedures. So we each knew what was expected of each other. We depended on each other, we integrated the astronauts in to doing the job in space and we did the job on the ground to keep them there and accomplish the missions.”

At the launch site, he said, “when you’re preparing a spaceship and something goes wrong, you try to figure out how to fix it. It’s a little different for the flight control team, because they didn’t have any spares around in a spaceship. So we had to try to figure out how to accomplish the mission even though the equipment was malfunctioning.”

The techniques pioneered by Kraft and young flight directors who followed in his footsteps, men like Gene “failure is not an option” Kranz, the urbane Glynn Lunney and more, saved the Apollo 13 crew from the brink of disaster in the aftermath of an explosion on the way to the moon that severely damaged the spacecraft.

Once comparing his complex work as a flight director to a conductor’s, Kraft said, ‘The conductor can’t play all the instruments, he may not even be able to play any one of them,'” Bridenstine said. “‘But, he knows when the first violin should be playing, and he knows when the trumpets should be loud or soft, and when the drummer should be drumming. He mixes all this up and out comes music. That’s what we do here.’”

Kraft was in the flight director’s chair at Cape Canaveral on May 5, 1961, when Alan Shepard blasted off aboard a Redstone rocket to become the first American in space. The flight came a month after the Soviet Union sent cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into orbit, a major psychological blow in the West at the height of the Cold War.

Shepard’s flight was a short, up-and-down suborbital mission, but it helped restore lost confidence and played a major role in President John F. Kennedy’s decision, announced on May 25, 1961, to commit the nation to sending an astronaut to the moon before the end of the decade. That promise was kept with the Apollo 11 moon landing 50 years ago on July 20, 1969.

“I had many proud moments,” Kraft recalled. “I think Alan Shepard was certainly a flight where I learned to be a flight director because until you put a human being on the end of a rocket, you don’t really understand the problem. I was pretty nervous, I was pretty exhilarated when it was over, as was Alan Shepard.

“Certainly, (John) Glenn’s flight was a great flight for all of us and then each one got better. Apollo 8 was probably my most exhilarating moment because I was the guy who had talked management into putting the vehicle around the moon and then in orbit around the moon. That was pretty exciting and pretty demanding on my heart, I suppose.”

Apollo 8 is considered one of NASA’s most daring missions. It marked only the third flight of a gargantuan Saturn 5 rocket, the first flight of the booster to carry a crew and the first mission to carry humans beyond low-Earth orbit.

“It was his legendary work to establish mission control as we know it for the earliest crewed space flights that perhaps most strongly advanced our journey of discovery,” Bridenstine said. “From that home base, America’s achievements in space were heard across the globe, and our astronauts in space were anchored to home even as they accomplished unprecedented feats.”

Born Feb. 28, 1924, in Phoebus, Virginia, Kraft earned a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering from Virginia Tech in 1944 and joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or NACA, the precursor to NASA. He later was assigned to the Space Task Group that spearheaded development of NASA’s Mercury program.

According to his book “Flight: My Life In Mission Control,” Kraft said his boss Chuck Matthews told him to “come up with a basic mission plan. You know, the bottom-line stuff on how we fly a man from a launch pad into space and back again. It would be good if you kept him alive.”

The mission control concept developed by Kraft called for a team of experts, focused on specific systems and subsystems, coordinated by a director, and all following a set of previously thought-out rules and procedures designed to handle virtually any eventuality.

“I saw a team of highly skilled engineers, each one an expert on a different piece of the Mercury capsule,” he wrote. “We’d have a flow of accurate telemetry data so the experts could monitor their systems, see and even predict problems, and pass along instructions to the astronaut.”

Kraft served as flight director for all six of the original one-man Mercury missions and seven of the 10 two-man Gemini flights that perfected the rendezvous and spacewalk techniques needed for the Apollo moon program. He served as director of flight operations until the Apollo 13 mission when he became deputy director of the Johnson Space Center.

He took over as director in 1972 and held the post until 1982, overseeing the center through the initial development of the space shuttle. He retired from NASA in 1982, but remained active as a consultant and NASA advisor. Appropriately enough, mission control at the Johnson Space Center was renamed in Kraft’s honor in 2011.

Always outspoken, in an interview for a NASA oral history project, Kraft described the space shuttle as the safest spacecraft ever built despite the booster O-ring failure that doomed the Challenger in 1986 and the foam debris that brought down Columbia in 2003.

“We had two failures, which were catastrophic. Both were the fallacies of man, not the fallacies of the machine,” he said. “(Challenger) was a failure of the human brain, not of the machine. We should have fixed it. Same is true of the debris. Eventually they were playing Russian roulette.

“So take what Chris Kraft says with a grain of salt. I say the machine has never really failed. There is no rocket, even with those two failures, that has the success rate of the space shuttle. It’ll be a cold day in hell when that is improved on.”