The privately-funded Israeli Bersesheet lander is on course to enter orbit around the moon April 4 after another boost from its main engine Tuesday.

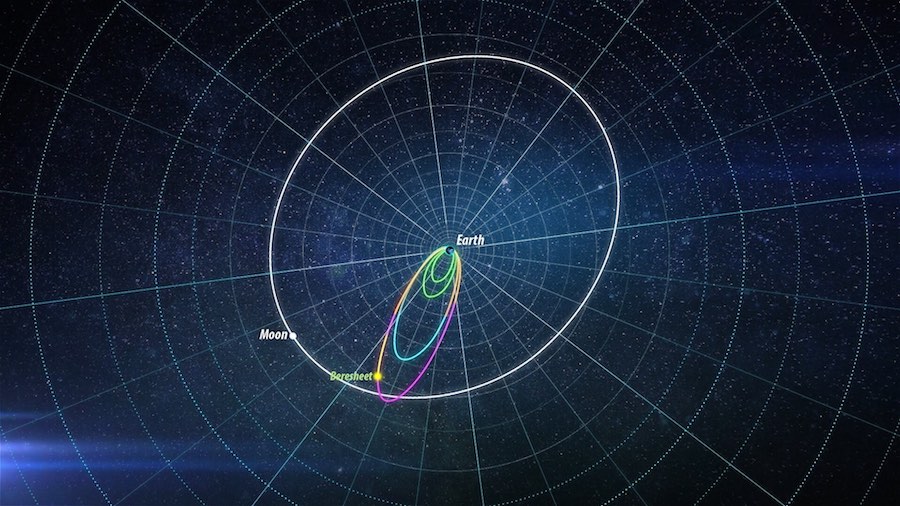

A 60-second firing by Beresheet’s 100-pound-thrust main engine at 8:30 a.m. EDT (1230 GMT) Tuesday raised the apogee, or high point, of the spacecraft’s elliptical orbit around the Earth to an altitude of more than 250,000 miles (405,000 kilometers), according to SpaceIL, the non-profit group that heads the privately-backed lunar lander mission.

“That’s enough to reach the distance of the moon from the Earth, and it’s actually our last maneuver to get closer to the moon,” said Opher Doron, general manager of Israel Aerospace Industries’ space division, which built the Beresheet spacecraft and operates the lander’s control center. “We will have a couple of more maneuvers over the following days that are small maneuvers to slightly adjust our trajectory, but we are on our way to the moon, very successfully, right now.”

Since its launch Feb. 21 from Cape Canaveral on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, the Beresheet lander has fired its main engine several times to raise its altitude closer to the moon. Beresheet, which means “genesis” or “in the beginning” in Hebrew, rode as a secondary payload on the Falcon 9 rocket, which delivered the lander, an Indonesian communications satellite and a U.S. Air Force smallsat to an egg-shaped supersynchronous transfer orbit ranging as high as 43,000 miles (69,000 kilometers) from Earth.

The Indonesian Nusantara Satu communications satellite and the Air Force’s S5 space surveillance craft maneuvered into geostationary orbit over the equator, while Beresheet began orbit-raising burns to head for the moon. Beresheet’s British-built LEROS 2b main engine, a modified version of an engine designed for commercial satellites, has conducted four orbit-raising firings since launch.

- Burn 1: Feb. 24 at 1129 GMT (6:29 a.m. EST); 30 seconds

- Burn 2: Feb. 28 at 1930 GMT (2:30 p.m. EST); 4 minutes

- Burn 3: March 7 at 1311 GMT (8:11 a.m. EST); 2 minutes, 32 seconds

- Burn 4: March 19 at 1230 GMT (8:30 a.m. EDT); 1 minute

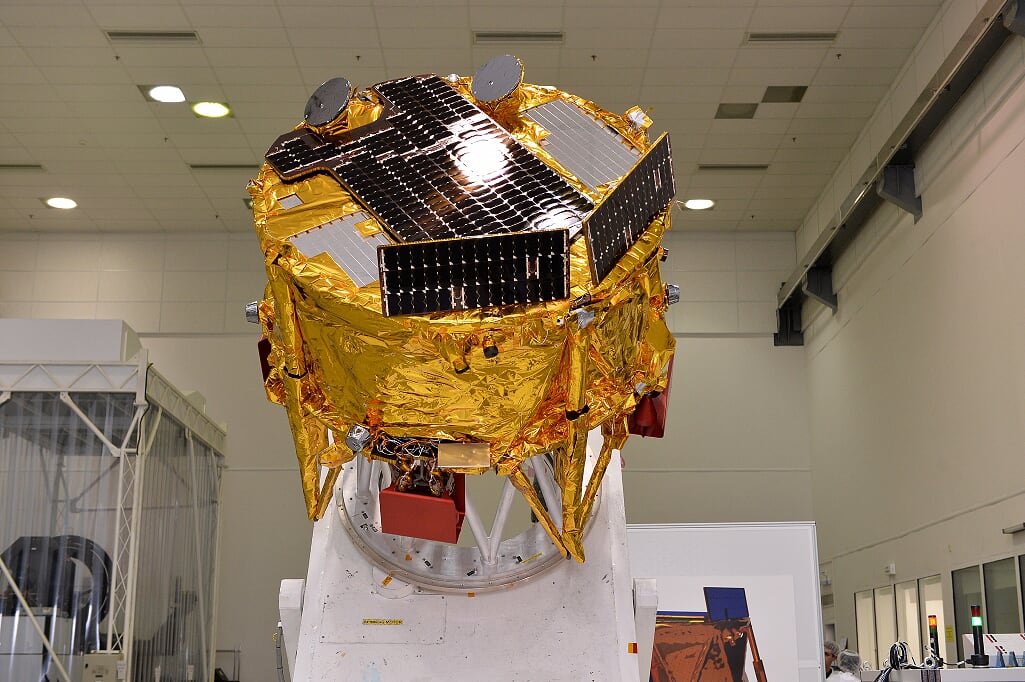

Ground controllers identified an issue with the spacecraft’s star tracker cameras shortly after launch. The cameras are used to locate the positions of stars in the sky, helping determine Beresheet’s orientation in space. SpaceIL says the star trackers are too sensitive to blinding by bright sunlight.

“We’ve learned to deal with difficulties we’ve been having with the star trackers, and what that entails in maneuvering the spacecraft in a non-nominal fashion,” Doron said Tuesday. “So that was working quite well today. We were lucky to have the engine firing in a communications pass. We actually saw it in real-time.”

With its four landing legs extended, Beresheet has a diameter of around 7.5 feet (2.3 meters), and measures 4.9 feet (1.5 meters) tall.

Beresheet’s main engine will fire again April 4 to steer into a preliminary orbit around the moon, followed by additional rocket burns to spiral closer to the lunar surface, setting up for landing April 11 on the moon’s Mare Serenitatis region.

The landing site is in the northern hemisphere of the moon’s near side, where cameras will capture panoramic views of the lunar surface, and a science instrument will measure the magnetic field. NASA also provided a laser reflector on the solar-powered spacecraft, which scientists will use to determine the exact distance to the moon.

The U.S. space agency is also providing communications and tracking support to the mission, and the German space agency, DLR, provided facilities for Israeli engineers to simulate Beresheet’s landing on the moon.

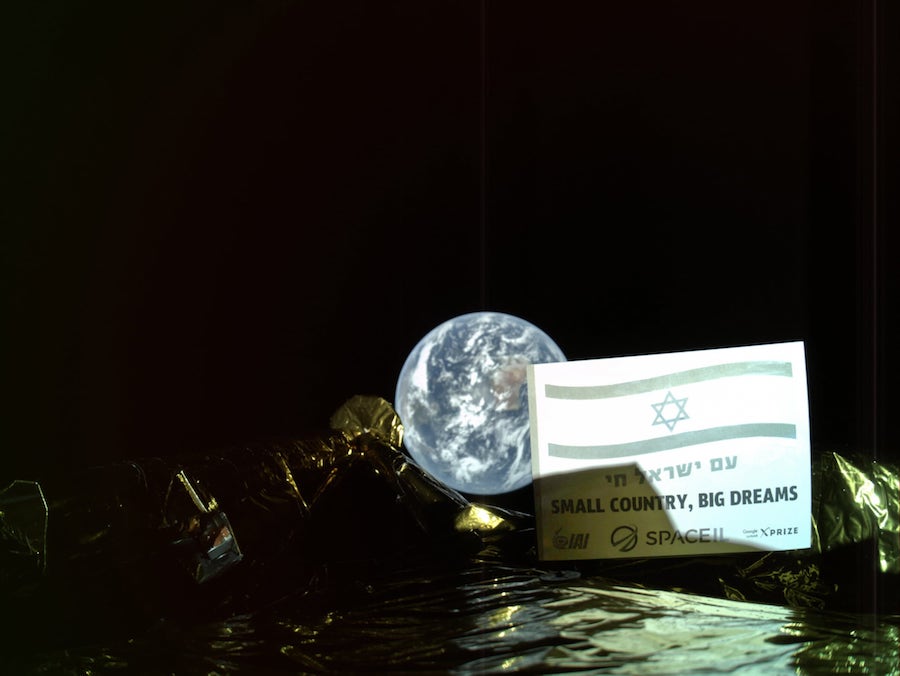

But Beresheet is privately-funded, and the mission aims to become the first to reach the moon without government backing. Billionaire philanthropists supported the $100 million mission’s development through financial contributions.

“We have a vision to show off Israel’s best qualities to the entire world,” said Sylvan Adams, a Canadian-Israeli businessman who contributed to the mission, in a press conference before Beresheet’s launch. “Tiny Israel, tiny, tiny Israel, is about to become the fourth nation to land on the moon. And this is a remarkable thing, because we continue to demonstrate our ability to punch far, far, far above our weight, and to show off our skills, our innovation, our creativity in tackling any difficult problem that could possibly exist.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.