EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated at 7 p.m. EST (0000 GMT) with additional photos, after the Falcon 9 rocket was raised vertical at pad 39A.

SpaceX’s first Crew Dragon spacecraft, fixed to the forward end of a Falcon 9 rocket, emerged Thursday from the company’s hangar at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the quarter-mile journey to its launch mount at pad 39A, where liftoff is scheduled early Saturday on a critical test flight before astronauts strap into the ship later this year.

The launcher was visible heading up the ramp to pad 39A shortly after 10 a.m. EST (1500 GMT) Thursday, once low-level fog began lifting at the Florida spaceport. The strongback transporter lifted the 215-foot-tall (65-meter) rocket vertical around 6 p.m. EST (2300 GMT) for final cargo loading and checkouts.

Spaceflight Now members can watch a live video feed of the rocket at pad 39A as SpaceX prepares for Saturday’s early morning launch. If you’re not a member, you can sign up today to support our coverage.

Liftoff is scheduled for 2:49 a.m. EST (0749 GMT) Saturday from Florida’s Space Coast, when Earth’s rotation brings pad 39A under the space station’s orbital plane, allowing the Crew Dragon to reach the research outpost in a little more than a day.

NASA and SpaceX officials met Wednesday for a launch readiness review, the last in a series of formal discussions on the status of the Crew Dragon, the Falcon 9 rocket, and the International Space Station, the mission’s destination. Mission managers decided to proceed with launch preparations, after a previous flight readiness review Feb. 22 gave a preliminary “go” for the flight.

The Crew Dragon is not carrying any astronauts on the upcoming mission, known as Demo-1 or DM-1, but engineers will assess the performance of the new human-rated capsule on a planned six-day flight. Docking with the International Space Station is scheduled Sunday around 6 a.m. EST (1100 GMT), assuming an on-time launch Saturday, followed by departure and splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean off of east coast of Florida on March 8 around 8:45 a.m. EST (1345 GMT).

“The task ahead of us is really historic,” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability.

The Crew Dragon will become the first human-rated spacecraft to launch from the Cape Canaveral spaceport since the last space shuttle mission lifted off in 2011. SpaceX uses the same Apollo- and shuttle-era launch facility — pad 39A — and gave the launch complex a facelift over the last few years, and began launching cargo and satellite missions there in 2017, giving the company a second launch pad in Florida.

SpaceX constructed a hangar, where Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets can be assembled, and stripped the launch pad of much of its shuttle-era equipment, including a rotating service structure no longer needed at the site. In August, ground teams installed a crew access arm, a boarding gate for astronauts. Finally, SpaceX painted the fixed tower black and added cladding, giving the historic pad a new look and providing additional protection from the seaside environment.

“Everything is in top condition,” Koenigsmann said. “Everything is freshly painted, it looks great. I’m really amazed by what this team in the past couple of weeks. I’m pretty sure we’re going to see a great launch and a great mission.”

NASA, SpaceX and Boeing — the agency’s other commercial crew partner — are on the precipice of launching astronauts. Boeing plans an unpiloted test flight — similar to the mission set for launch by SpaceX this weekend — later this spring, followed by crewed test flights by both companies later this year.

“It brings an excitement back to KSC that we haven’t seen in a while,” said Joel Montalbano, NASA’s deputy space station program manager. “You can just tell, by this last month, when people are just (excited). We’re ready, they’re looking forward to the launch this weekend.”

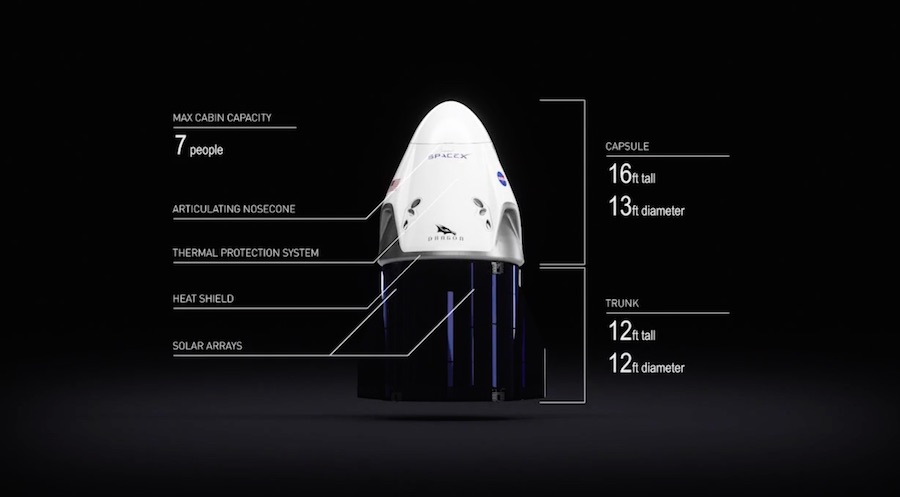

The long-delayed Crew Dragon test flight will wring out the capsule’s systems, ranging from life support to propulsion, power, navigation, and safety technology. While it shares some design history with SpaceX’s Dragon cargo capsule, which has launched 18 times — including on a failed mission and two test flights — the Crew Dragon is essentially a new spacecraft.

For the first time, SpaceX will fly a spacecraft with crew displays, seats, and the air revitalization system necessary to sustain crews during the trip from Earth to the space station and back. The Crew Dragon also carries a new docking system, a redesigned power generation system with body-mounted solar panels, an upgraded cooling system with a radiator, and new SuperDraco thrusters designed to propel the capsule away from an exploding rocket.

SpaceX also added a crew hatch, and the Crew Dragon has a different outer mold line, giving it a different aerodynamic shape.

Filled with hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellants, the Crew Dragon will be the heaviest payload ever launched by SpaceX. Here are some statistics on the Demo-1 mission and the Crew Dragon spacecraft, provided by NASA:

- Crew Dragon Mass at ISS Docking: 26,577 pounds (12,055 kilograms)

- Crew Dragon Total Height: 26.7 feet (8.1 meters)

- Falcon 9/Crew Dragon Total Height: 215 feet (65 meters)

- Crew Dragon Capacity: 7 astronauts (4 astronauts plus cargo for NASA missions)

- Crew Dragon Design Life: At least 210 days (when docked to ISS)

- Cargo on Demo-1: 449.7 pounds (204 kilograms)

- Demo-1’s Planned Mission Duration: 6 days, 5 hours, 55 minutes

“From a NASA perspective, we’re really wanting to see the on-orbit performance, how the systems are going to be working together, the key avionics and docking, making sure communications and telemetry with the International Space Station is working properly,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA’s commercial crew program manager. “We’re going to be learning from the ECLSS (environmental control and life support) systems and the power systems.”

A spacesuit-clad anthropomorphic test device — which SpaceX officials prefer to call a “smarty” and not a “dummy” — is sitting in one of the four seats inside the Crew Dragon.

SpaceX has named the mannequin “Ripley,” after Sigourney Weaver’s character in the “Alien” films.

According to SpaceX, Ripley is fitted with sensors around its head, neck and spine to gather data on the environments astronauts will experience when they ride the Crew Dragon, beginning later this year on the capsule’s second test flight.

“The goal is to get an idea of how humans would feel in her place, basically,” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability. “I don’t expect, actually a lot of surprises there. But it’s better to verify, make sure that it’s safe and everything is comfortable for our astronauts going on the next flight of our capsule.”

Musk tweeted that cameras inside the spacecraft will provide views during the Crew Dragon’s trip to the International Space Station, including views from Ripley’s perspective, with cockpit display panels within reach.

The start of regular crew rotation service by SpaceX and Boeing will allow NASA to stop buying seats for U.S. and partner astronauts on Russian Soyuz spacecraft, the only vehicle currently capable of carrying humans to space station. After completing their test flights, the SpaceX Crew Dragon and Boeing CST-100 Starliner spacecraft will ferry astronauts to and from the station for six-month stays, and remain docked at the research complex to serve as emergency lifeboats.

NASA started paying companies to develop commercial crew vehicles in 2010. After several funding rounds, the space agency selected Boeing and SpaceX in 2014 to complete their human-rated Starliner and Crew Dragon capsules.

At that time, SpaceX said the Crew Dragon’s unpiloted demonstration flight could be ready to take off by the end of 2016. After more than two years of delays, during which SpaceX redesigned the craft to return to Earth in the ocean rather than on land, the Crew Dragon is ready for blastoff Saturday.

Through several funding agreements and contracts, NASA has paid SpaceX more than $3.14 billion over the last decade to work on the Crew Dragon spacecraft, human-rate the Falcon 9 launcher, and ready the company’s launch pad and control center for astronaut missions.

Boeing has received $4.82 billion in that time to design, develop and test the Starliner spacecraft, which will lift off on United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rockets and return to Earth with a airbag-cushioned landings in the Western United States, likely in New Mexico for the first test flights. The Starliner has also encountered delays, stemming from issues with the capsule’s aerodynamics, abort thrusters, and other issues.

Once the Crew Dragon splashes down in the Atlantic — around 240 miles (390 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral — a SpaceX recovery ship will retrieve the capsule from the sea and return it to port. SpaceX aims to reuse the capsule for an in-flight abort test, tentatively scheduled for June, to verify the performance of the ship’s escape engines.

The in-flight abort test will verify the Crew Dragon’s SuperDraco escape thrusters can push the capsule away from a failing rocket, a safety feature designed to ensure astronauts survive a launch accident.

Eight SuperDraco rocket engines mounted in pods around the circumference of the Crew Dragon are programmed to quickly fire if computers detect an emergency during launch. NASA and SpaceX want to ensure the escape system is up to the job before putting astronauts on the spacecraft.

SpaceX tested the abort system during an on-pad test in 2015, demonstrating the SuperDracos have the power to drive the spacecraft off its rocket sitting on the ground in the event of an accident during the countdown.

For the Demo-1 mission, the escape system is operating with reduced functionality to gather data.

The second Crew Dragon test flight, with two NASA astronauts on-board, is planned as soon as July. But that’s a best-case scenario, and sources familiar with the program suggest the mission is likely to be pushed back until later in the year.

SpaceX plans to retire its first-generation Dragon cargo capsule next year, and move all of its space station flights — carrying crew and supplies — to the new-generation Crew Dragon design.

“It’ll be more exciting when we come back for DM-2, when we put Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley on top of that rocket for their test mission,” said Pat Forrester, a three-time space shuttle flier and chief of NASA’s astronaut corps. “But even though a lot of progress has been made, there’s still a lot of work that we need to do. We’re looking forward to working as a team with SpaceX to get that done.”

Under the terms of its contract with NASA, SpaceX also designed new sleek-looking spacesuit for astronauts riding on Crew Dragon.

There’s still work to complete on qualifying the Crew Dragon’s four landing parachutes for crewed flights, and engineers are modifying part of the capsule’s propulsion system to address a vibration concern with the ship’s Draco thrusters.

“The launch early in the morning on Saturday is definitely a milestone,” Forrester said. “There’s another milestone … and that’s on Sunday when this thing docks to the International Space Station. Because although we don’t have any astronauts on DM-1, we do have them on the space station.”

The station astronauts will have the ability to send the Crew Dragon away if it runs into problems during the rendezvous. The capsule will attempt SpaceX’s first docking with another object in space, targeting arrival at a new docking port delivered to the station by a SpaceX cargo capsule in 2016.

One safety concern about the docking voiced by Russian officials at a readiness review last week as closed out Wednesday, according to Montalbano. Russian engineers were concerned that the Crew Dragon does not have an independent command chain to safely fly away from the station if it suffers a total computer failure during the final approach for docking.

Montalbano said NASA assuaged Russian worries by instructing the space station crew to close hatches inside the complex during Crew Dragon’s rendezvous, allowing the astronauts to quickly seal off any air leak in the event of a collision. The station crew will also have a clear path to their Soyuz return craft to evacuate if necessary.

“Despite the fact that there’s no one launching, there is always human life at risk,” Forrester said. “So we want to stay focused, we want to stay vigilant, and we want to continue to move down this path that we’ve started.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.