An Israeli-built moon lander aiming to become the first privately-funded mission reach another planetary body rocketed away from Cape Canaveral on Thursday night aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, riding piggyback with an Indonesian communications spacecraft and an experimental U.S. Air Force space surveillance microsatellite.

The Falcon 9 rocket fired away from Florida’s Space Coast atop 1.7 million pounds of thrust, heading east on a trajectory arcing over the Atlantic Ocean on a thundering departure which marked the first launch of the year from Cape Canaveral.

Nine Merlin 1D main engines ignited in the final three seconds of Thursday night’s countdown, and hold-down restraints released the 229-foot-tall (70-meter) launcher at 8:45 p.m. EST (0145 GMT Friday). After turning to the east from the Florida coast, the Falcon 9 exceeded the speed of sound in less than a minute and shut down its first stage engines a little more than two-and-a-half minutes into the mission.

The booster stage jettisoned seconds later to begin a guided supersonic plunge back into the atmosphere, reigniting a subset of its engines to steer toward a landing platform in the Atlantic Ocean. The booster extended a landing gear and used one of its engines to brake for touchdown on the drone ship, named “Of Course I Still Love You.”

The on-target landing ended the third trip to space and back for the Falcon 9 booster, following a pair of missions launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California last year. It was the 34th successful landing of a Falcon booster overall.

The Falcon 9’s upper stage engine propelled the mission’s three payloads into an oval-shaped orbit using two separate firings within a half-hour of liftoff. The rocket intended to reach an orbit ranging more than 37,000 miles (60,000 kilometers) above the planet at its highest point, and SpaceX’s launch team reported the Falcon 9 achieved an on-target orbital insertion.

The Israeli moon lander, named Beresheet, was the first of the three spacecraft on the mission to separate in orbit around 33 minutes after liftoff. The Indonesian Nusantara Satu communications satellite, the mission’s heaviest payload, deployed 44 minutes into the flight, and a forward-looking camera on the Falcon 9 rocket showed the telecom craft receding into space as the vehicles soared over the Indian Ocean.

The successful launch Thursday night cleared the way for SpaceX’s first Crew Dragon capsule to blast off from the Kennedy Space Center as soon as March 2. The Crew Dragon spacecraft, developed under contract to NASA, is set for an unpiloted test flight to the International Space Station before a mission with astronauts on-board later this year.

A Flight Readiness Review for the Crew Dragon demonstration flight is scheduled Friday, when NASA and SpaceX managers will examine the mission’s flight plan and discuss any unresolved technical concerns before deciding whether to proceed with launch preparations for a March 2 liftoff.

Israel’s Beresheet mission begins seven-week trip to the moon

Within minutes of separation from the Falcon 9 rocket, the Beresheet moon probe opened its four landing legs and radioed ground controllers in Israel with a status report.

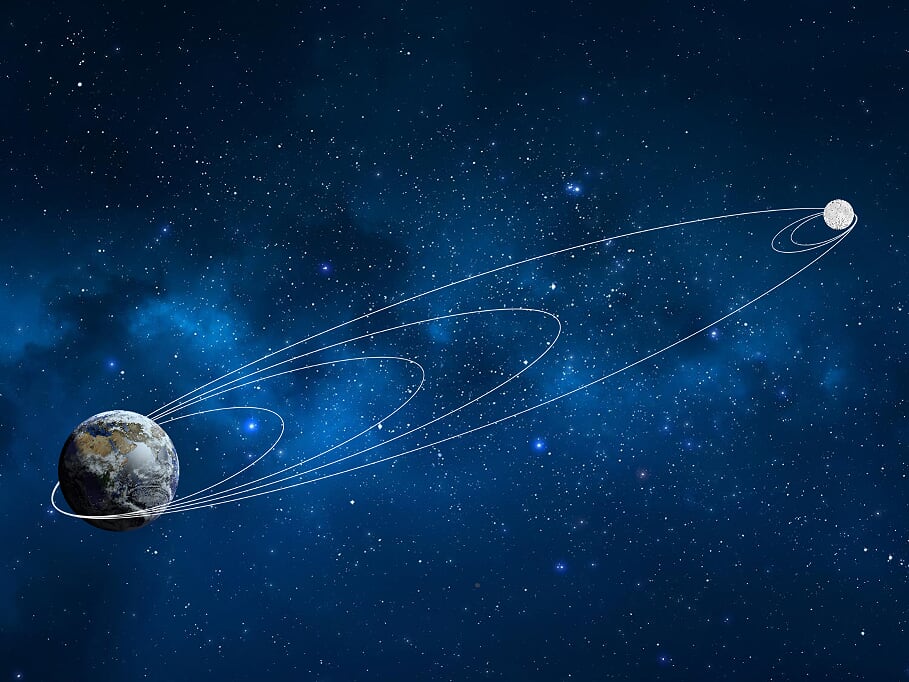

The moon-bound lander will fire its main engine several times in the coming weeks, beginning as soon as Friday, to raise its altitude with a series of ever-growing loops around the Earth, setting up for a maneuver to wring into lunar orbit April 4. Touchdown in the moon’s Mare Serenitatis region is scheduled for April 11.

Funded by philanthropists and donors, the mission could make history and become the first privately-funded spacecraft to reach the moon.

A non-profit group named SpaceIL spearheaded the project, which officials said cost less than $100 million from conception through the launch.

“This is going to be the first private interplanetary mission that’s going to go to the moon,” said Yonatan Winetraub, a co-founder of SpaceIL, which had its origin in a brainstorming meeting in a Tel Aviv bar. “This is a big milestone. This is going to be the first time that it’s not going to be a superpower that’s going to go to the moon. This is a huge step for Israel.

“Until today, three superpowers have soft landed on the moon — the United States, the Soviet Union and recently, China,” Winetraub said in a news conference Wednesday night in Orlando. “And (we) thought it’s about time for a change. We want to get little Israel all the way to the moon. This is the purpose of SpaceIL.”

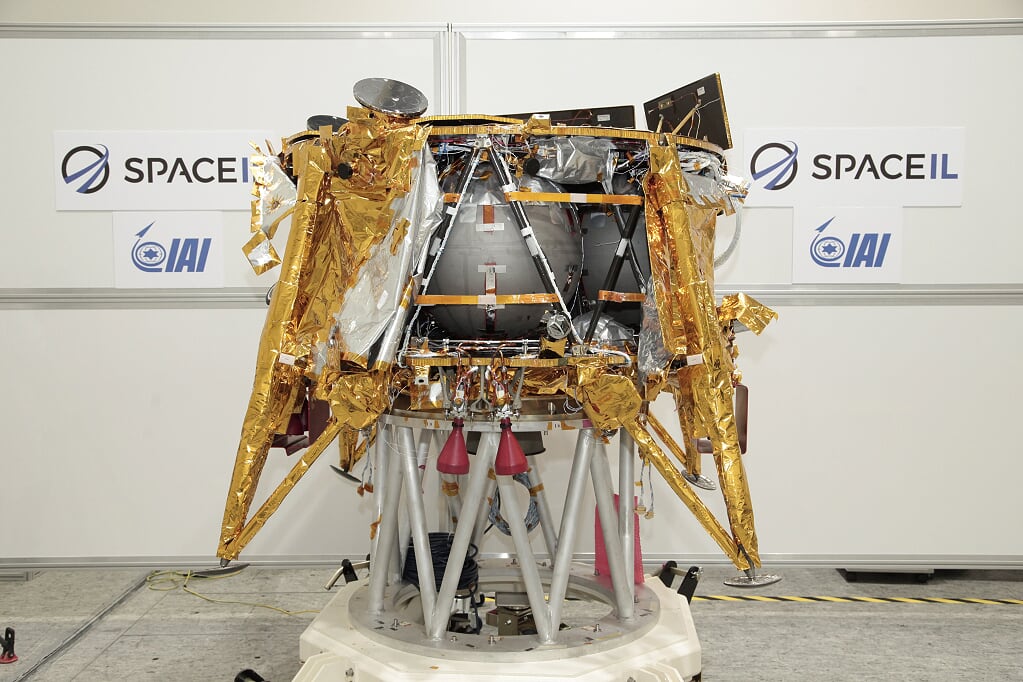

Beresheet, which means “genesis” or “in the beginning” in Hebrew, is covered in gold insulation. Nearly three-quarters of the spacecraft’s 1,290-pound (585-kilogram) launch mass is hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide propellant contained within tanks inside the lander’s body.

The propellants will feed a 100-pound-thrust main engine adapted from communications satellite buses, along with eight control jets to keep the Beresheet lander properly pointed.

“Israel is a very small country, as small as New Jersey, and we’re shooting for the moon,” said Yigal Harel, head of SpaceIL’s spacecraft development team. “It’s the first time a small country has aimed to reach the moon and land safely. We are the first non-governmental mission to the moon, and we’re the first ever moon mission to use a commercial launch, which is very unique.”

Originally conceived as a competitor for the Google Lunar X Prize, the SpaceIL lunar lander was manufactured by Israel Aerospace Industries, an Israeli defense contractor, and delivered to Cape Canaveral in January for the rideshare launch on the Falcon 9 rocket.

The Google Lunar X Prize, which promised a multimillion-dollar cash payout to the first team that put a privately-funded spacecraft on the moon, ended last year without a winner.

Morris Kahn, an Israeli billionaire, put $40 million of his fortune toward the mission, and serves as SpaceIL’s president. Other donors include Miriam and Sheldon Adelson, a casino and resort magnate who lives in Las Vegas, and Sylvan Adams, a Canadian-Israeli businessman.

The financial backers decided to keep SpaceIL going after the Google Lunar X Prize ended.

“We have a vision to show off Israel’s best qualities to the entire world,” Adams said Wednesday. “Tiny Israel, tiny, tiny Israel, is about to become the fourth nation to land on the moon. And this is a remarkable thing, because we continue to demonstrate our ability to punch far, far, far above our weight, and to show off our skills, our innovation, our creativity in tackling any difficult problem that could possibly exist.”

“We’ve been at it for six, seven, or eight years low-key, and for about four years at full rate,” said Opher Doron, general manager of IAI’s space division. “That’s what it took to develop the spacecraft. So it’s a new business model, and it’s a totally new way of getting to the moon.”

Because of the project’s limited budget — a fraction of the cost of government-funded lunar landers — the Israeli team had to adapt technology designed for other purposes to the moon mission. For example, the main thruster on the lander is an off-the-shelf engine typically used to adjust the orbits of large communications satellites.

The engine can’t be throttled, so it will fire in short bursts — as needed — to control the lander’s descent rate, before shutting off around 16 feet (5 meters) above the moon, allowing the probe to fall to the surface.

“It’s extremely exciting, and quite risky,” Doron said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “There’s no guarantee of success. There never is in space, but there’s even less so in this case. But we’ve done a lot of testing, a lot of engineering, and now we’ll be doing a lot of praying.

“We have to live in space for a month-and-a-half without redundancies,” Doron said. “That’s never trivial, when we have so many new systems on-board. But the riskiest part is the lunar capture, and by far the riskiest is the landing itself. We’ll be doing more than a week in lunar orbit. We will raise our apogee until we get to the distance of the moon, and we have to time that so that when the moon is crossing our plane, that’s when we get there. We have to time our orbit-raising maneuvers so that when the moon is at that spot, we get there as well.”

“What we are trying to do here is take $100 million and put a few kilograms on the moon, but we are doing it at a certain level of reliability, which we currently don’t know,” Harel said. “For sure, it’s not 100 percent. This mission is very, very ambitious.”

“I think it’s an extraordinary success right where we stand right now,” Doron said. “We have designed and built and shipped a spacecraft ready to launch on the way to the moon. As someone from NASA told me, even if we don’t make it, we’ll be the first ones to figure out what went wrong and try to fix it.”

If the touchdown is successful, Beresheet will collect data on the magnetic field at the landing site. NASA also provided a laser reflector on the spacecraft, which scientists will use to determine the exact distance to the moon. The U.S. space agency is also providing communications and tracking support to the mission.

The German space agency — DLR — also helped the SpaceIL team with drop testing to simulate the conditions the spacecraft will encounter at the moment of landing.

But Doron said the Beresheet spacecraft is largely home-grown, with Israeli designers, builders and operators.

“When you zoom out a little bit and you remember what the Google Lunar X Prize — rest in peace — wanted to achieve, we’ve actually achieved it,” Doron said. “We’re actually managing to do what they wanted to show was possible, a non-government mission to get to the moon.”

The Israeli-built lander is designed to function at least two days on the moon, enough time to beam back basic scientific data and a series of panoramic images, plus a selfie. The laser reflector is a passive payload, and will be useful long after the spacecraft stops operating.

Beresheet also aims to deliver a time capsule to the moon with the Israeli flag, and digital copies of the Israeli national anthem, the Bible, and other national and cultural artifacts.

“People say during the ’60s, Russia and the United States landed on the moon, so what’s the big deal now?” Harel said. “The tooling of development changed a lot, but the physics of nature is still very harsh and very, very complex, and to take something so tiny and so fragile and to put it on the moon is a very complex and ambitious mission. So we have redundancy only on things we decided must have it, but most of the systems have no redundancy.

“We need to be creative, when we encounter problems — and for sure, we will encounter problems because this is the space arena — we will have to send commands to the software of the spacecraft to do things differently.”

IAI and OHB, a German aerospace company, signed an agreement in January that could build on the Beresheet mission by constructing future commercial landers to ferry scientific instruments and other payloads to the moon’s surface for the European Space Agency.

According to Doron, IAI is also in discussions with U.S. companies to use Israeli technology developed for the Beresheet project on commercial lunar landers for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. NASA selected nine companies last year to be eligible to compete for contracts to transport science and tech demo payloads to the lunar surface.

SpaceIL and IAI were not among the winners, but Israeli engineers could partner with U.S. firms to meet NASA’s requirements.

“There may be opportunities in the United States,” Doron said. “There’s the CLPS program in the United States, and we are talking to different U.S. companies about how we can join in that.”

Indonesian telecom satellite, U.S. Air Force experiment on the way to geosynchronous orbit

The Indonesian Nusantara Satu communications satellite, built by SSL in Palo Alto, California, was the the primary passenger on the Falcon 9 launcher. A U.S. Air Force satellite, known as S5, will also ride piggyback on an adapter attached to the top of Nusantara Satu.

The entire spacecraft stack weighed about 10,700 pounds (4,850 kilograms), according to SSL, which sold some of capacity it purchased on the Falcon 9 rocket to Spaceflight, a company that offers rideshare launch opportunities to small satellites that do not require the full capability of a large rocket.

Spaceflight booked contracts with SpaceIL and the U.S. Air Force to give the Beresheet lander and the S5 space surveillance satellite rides into space. The launch marks the first rideshare to a geostationary-type orbit for Spaceflight, which until now has launch smallsats into low Earth orbits a few hundred miles above the planet.

While Beresheet separated from the multi-satellite stack Falcon 9 soon after launch, the Air Force’s S5 smallsat will remain attached to the Nusantara Satu spacecraft until it reaches an orbit near geostationary altitude more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) above the equator, where S5 will deploy to begin its mission.

Nusantara Satu will then continue to its final orbital position in geostationary orbit to begin a 15-year telecommunications mission over Indonesia and Southeast Asia.

The satellite, with a fueled weight of more than 9,000 pounds (4,100 kilograms), is owned by PT Pasifik Satelit Nusantara, or PSN, an Indonesian telecom company. Formerly known as PSN 6, the satellite carries C-band and Ku-band transponders, along with a high-throughput payload for broadband services.

“(The) Nusantara Satu satellite is a very important infrastructure for Indonesia,” said Adi Rahman Adiwoso, CEO of PSN. “As the first Indonesian High Throughput Satellite, it is another monumental step for PSN to realize its dream and carry on its commitment to provide broadband services across the vast archipelago of Indonesia.”

A mix of conventional liquid-fueled thrusters and an electric propulsion system will push the Nusantara Satu spacecraft toward its final perch in geostationary orbit at 146 degrees east longitude.

S5 was described as a space situational awareness mission in a 2017 press release from Blue Canyon Technologies, a smallsat manufacturer in Colorado.

According to Blue Canyon Technologies, the spacecraft weighs about 132 pounds (60 kilograms), and carries a payload provided by Applied Defense Systems.

The U.S. military has launched several missions in recent years with optical sensors to scan geostationary orbit, where ground-based radars used to track satellites and space junk in low Earth orbit have difficulty detecting objects.

One such mission was SensorSat, which launched from Cape Canaveral in August 2017 to look up toward geostationary orbit from a low-altitude orbit hugging the equator. The Air Force has also launched four space surveillance satellites to rove geostationary orbit, with the ability to approach and inspect objects there.

S5 will demonstrate the capability of a small satellite to find objects in geostationary orbit, allowing the military to update its database, which is relied upon by commercial companies and international space agencies.

“The objective of the S5 mission is to measure the feasibility and affordability of developing low cost constellations for routine and frequent updates to the GEO (geostationary) space catalog,” Blue Canyon Technologies said in the 2017 statement.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.