Eight months after last hearing from the Opportunity rover, NASA officials announced the end of the craft’s 15-year mission Wednesday, closing out an ambitious chapter of Mars exploration that proved the Red Planet once harbored running water and demonstrated the promise of mobile robotic scouts to survey other worlds.

The rover succumbed to a sky-darkening global dust storm, and last communicated to Earth on June 10, 2018. Mission officials hoped to regain contact with Opportunity after the dust storm cleared, but daily listening sessions and more than 1,000 tries to send commands to the rover produced no results.

Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science mission directorate, declared the end of Opportunity’s mission in a press conference Wednesday at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

“I was there yesterday, and I was there with the team as these commands went out into the deep sky, and I learned this morning that we had not heard back, and our beloved Opportunity remains silent,” Zurbuchen said. “I am standing here with a sense of deep appreciation and gratitude to declare the Opportunity mission as complete, and with it the Mars Exploration Rover mission as complete.”

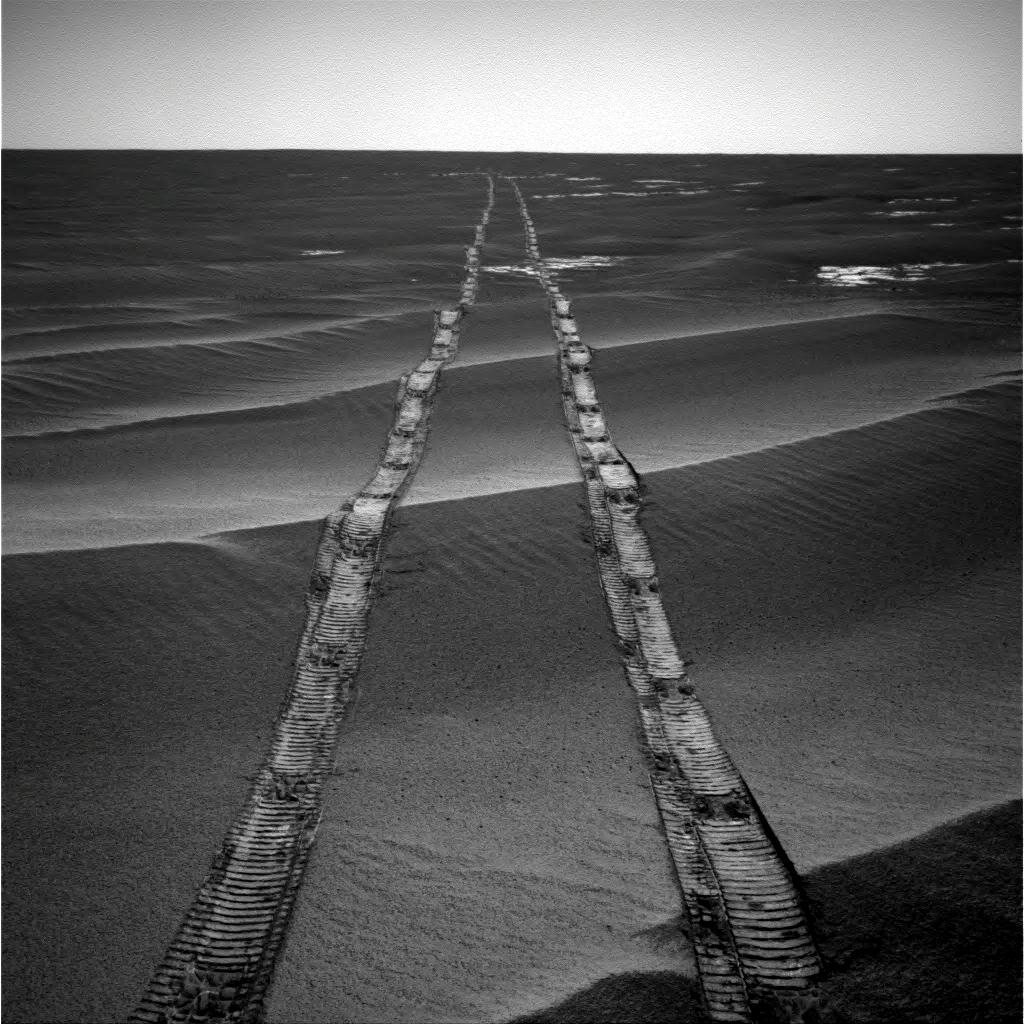

Opportunity landed on Mars on Jan. 24, 2004, to begin a mission that was not planned to last more than 90 days. Instead, Opportunity returned data for more than 14 years — nearly 60 times longer than its designed lifetime — and logged more than 28 miles (45 kilometers) on its odometer, farther than any other robot has driven on another world.

“I have to tell you, this is an emotional time,” Zurbuchen said.

Opportunity and its twin rover, Spirit, launched in 2003 from Cape Canaveral aboard a pair of Delta 2 rockets. After reaching the Red Planet in January 2004, both of the 384-pound (174-kilogram) rovers — each about the size of a golf cart — set out to explore their surroundings, climbing hills and descending into craters in search of geologic clues about the ancient history of Mars.

Spirit ended its mission in March 2010, after getting stuck in sand with its solar panels in an unfavorable orientation to generate power during a harsh Martian winter.

“We were meant to get to this point, to wear these rovers out, to leave behind no unutilized capability on the surface of Mars, but we had no idea it would take this long,” said John Callas, Opportunity’s project manager at JPL. “But even still, this is a hard day, and this is hard for me because I was there at the beginning.”

“Spirit and Opportunity may be gone, but they leave us a legacy, and that’s a legacy of a new paradigm for solar system exploration,” said Mike Watkins, director of JPL. “A robotic geologist on Mars, and an integrated science and engineering (and) operations team here on Earth all set out together on a mission of discovery. They didn’t know what they would find, they didn’t know what direction they would go, sometimes from one day to the next, and they made it work. And they made it work longer than any of us thought possible, by both brilliant scientific deduction of where to go and brilliant engineering to keep the rovers alive.”

“It’s a team that makes success like this,” Zurbuchen said. “It’s a team that creates exploration, transformative exploration, for science and engineering, and it’s a team that is celebrating here today, emotionally.”

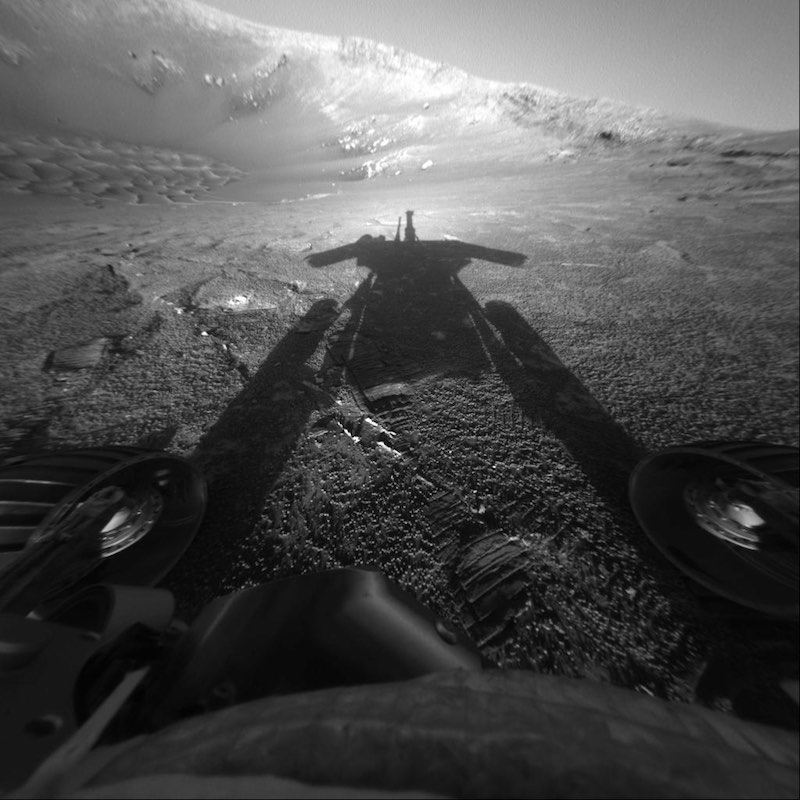

Skies over the Opportunity rover blackened last June as a global dust storm enveloped Mars and starved the robot’s solar panels of sunlight. It was the most extreme dust storm observed by Spirit or Opportunity since their landings in 2004.

Ground controllers regularly listened for a call from Opportunity after losing communications with the rover, using giant dish antennas from NASA’s Deep Space Network to try and detect a signal. Engineers hoped the rover would automatically wake up and radio Earth when the dust storm cleared, but that did not happen. Managers then prepared commands to send up to Opportunity “in the blind,” hoping that a gust of wind would clear the solar panels of dust and bring the robot back to life.

Opportunity’s ground team sent up the last such command Tuesday night. After the signal took 13-and-a-half minutes to reach Mars — traveling at the speed of light — Opportunity should have sent a response back to engineers keeping vigil in a control room at JPL. Silence reigned.

“We tried valiantly over these last eight months to try to recover the rover, to get from signal from it,” Callas said Wednesday. “We’ve listened every single day with the Deep Space Network, with our sensitive receivers, and we sent over 1,000 recovery commands trying to exercise every possibility of getting a signal from the rover. But with time, the skies are darkening, it’s getting colder on Mars, we recently passed through the historic dust-cleaning season on Mars to see if that would help … That brought us to last night, we sent our final commands, and we heard nothing, so it comes time to say goodbye.”

NASA spent around $800 million — in 2003 economic conditions — to build and launch the Spirit and Opportunity rovers.

“Spirit and Opportunity were robotic field geologists,” said Steve Squyres, lead scientist for the twin rovers from Cornell University. “Geology is a forensic science. A geologist is like a detective at the scene of a crime. Something happened at this place on Mars billions of years ago. What was it? What was it like there back then? And you’re looking for clues, and the clues are in the rocks. So we equipped these vehicles with the tools that they needed to read those clues.”

After a six-month journey from launch, Opportunity dropped to an airbag-cushioned landing at Meridiani Planum, a smooth equatorial plain, and rolled into a 72-foot-wide (22-meter) crater, a fortuitous interplanetary “hole-in-one” that presented scientists with a treasure trove of layered bedrock exposed by an ancient asteroid impact.

“The first day that we landed, it was geologic pay dirt right from the very beginning,” Squyres said.

“I remember the emotions,” Zurbuchen said. “I saw that Cornell professor (Squyres) jumping up and down like my 4-year-old on his birthday when entry, descent and landing was complete, and the rover said, ‘I’m here.'”

Within weeks, Opportunity discovered evidence that liquid water once flowed across the Martian surface at the Eagle Crater site.

“But it wasn’t nice stuff,” Squyres said Wednesday. “You know, we were running around saying, ‘Water on Mars! Water on Mars!’ It was really sulfuric acid on Mars. The pH was very low, this was very acidic stuff, it was very salty. This was not evidence of an evolutionary paradise, but it was a fascinating, fascinating environment.”

Opportunity drove to two bigger nearby craters — Endurance and Victoria — for an extended mission, then Squyres and his deputies decided to dispatch the rover across a barren stretch of Meridiani Planum, riddled with sand dunes, toward 14-mile-wide (22-kilometer) Endeavour Crater.

The cross-country trip took three years.

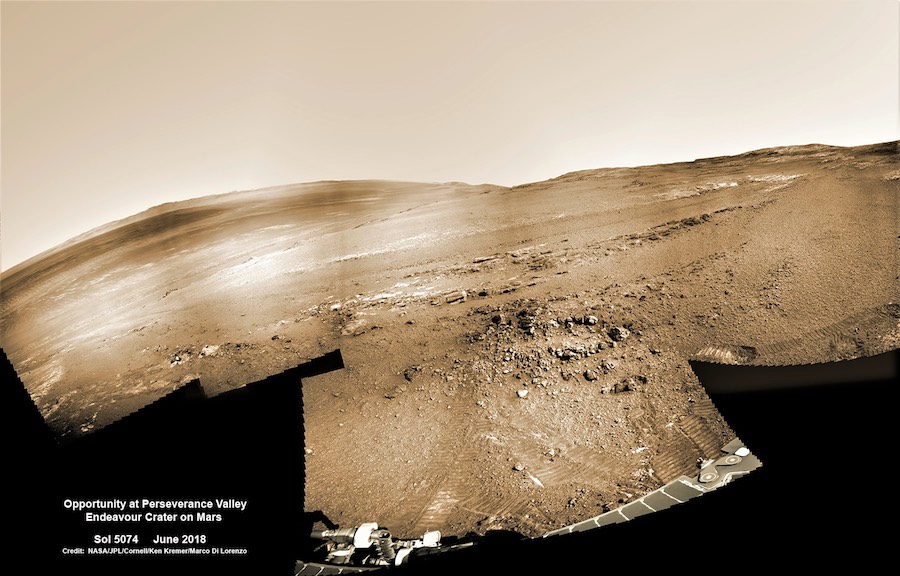

“When we got there, the mission started all over again,” Squyres said “New rocks, new stories, looking in the very distant past.”

“We were able, at the rim of Endeavour Crater, to find rocks that were probably the oldest observed by either one of the rovers,” he said. “And those told a story of water coursing through the rocks, but with a neutral pH. It was water you could drink, so we were about to piece together a new story there. That was one of the mission’s most significant discoveries, and it came 11 years into our 90-day mission.”

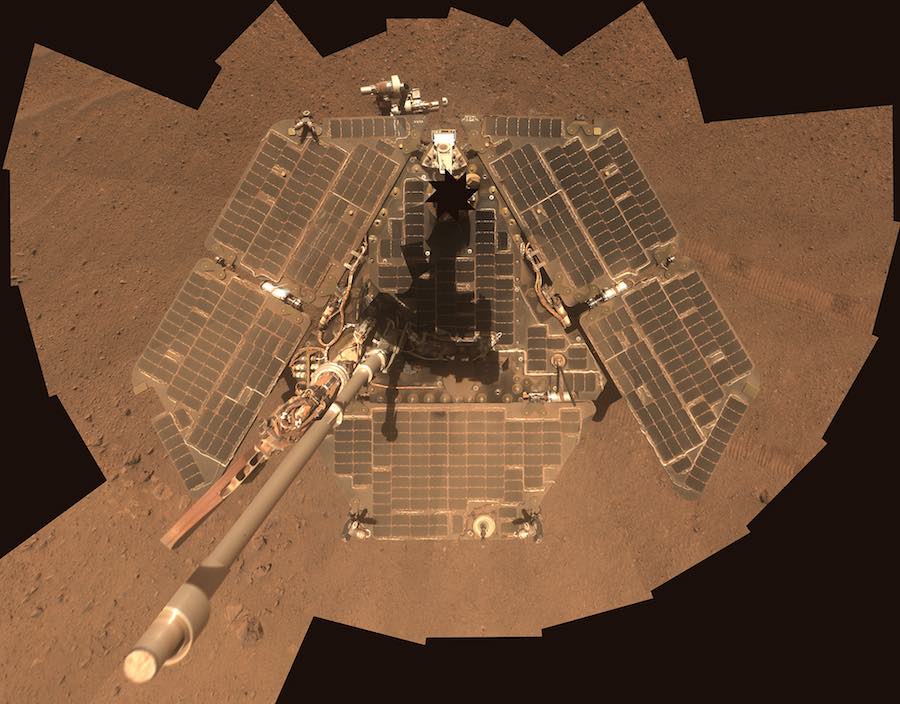

Opportunity took 217,594 raw images on Mars, nearly double the number captured by Spirit.

Abigail Fraeman, Opportunity’s deputy project scientist, was a junior in high school when the rover returned the first set of images soon after landing in Eagle Crater. She was at JPL for the landing, thanks to an educational project provided by the Planetary Society.

“It was those first images from Opportunity that inspired me to become a planetary scientist,” she said. “They revealed a view of Mars that we had never seen before.

“I’ve been hearing a lot of people’s stories,” Fraeman said. “What strikes me as so cool is that this story is not unique for me. There really are hundreds, if not thousands, of students who were just like me, who witnessed these rovers and followed along (with) their mission from the images they released to the public over the last 15 years, and because of that went to pursue careers in science, education and math.”

Callas counted the intergenerational team as “one of the most rewarding legacies” of the Spirit and Opportunity rovers. Scientists and engineers brought up with the Mars rovers will go on to support future space missions, such as the Curiosity rover still exploring Mars, or the Mars 2020 mission set for departure to the Red Planet next year, he said.

“We built them for Mars. That’s the place where they were designed to go. That’s their home, that’s where I would like them to stay. Also, if you had the opportunity to bring 180 kilograms of stuff back from the surface of Mars, the last thing I want to bring is something I know exactly what it’s made of,” joked Steve Squyres, Mars Exploration Rover principal investigator from Cornell University, in response to a question about retrieving the rovers and returning them to Earth.

“Why did these rovers last so long? Why did Opportunity last so long? There are two main technical reasons,” Callas said. “One is that we had expected that dust falling out of the air would accumulate on the solar arrays and eventually choke off power after about 90 days. But what we didn’t expect that wind would come along periodically and blow the dust off the arrays. This on a seasonal cycle actually became pretty reliable, and allowed us to survive not just the first winter, but all the winters we experienced on Mars, and to keep going and exploring.

“The other thing was that these rovers actually have the finest batteries in the solar system,” Callas said. “They had over 5,000 charge-discharge cycles on them, and they still had about 85 percent of their capacity. I mean, we’d all love it our cell phone batteries lasted this long, but that really was an enabling capability, that with the dust cleaning and the batteries allowed us to have that critical energy that we needed to get through the coldest, darkest parts of the winter on Mars, and to keep exploring.”

Opportunity suffered from a type of amnesia. A flaw in the rover’s flash memory forced ground controllers to retrieve imagery, science data and housekeeping telemetry before Opportunity went into hibernation every night, then start fresh again the next morning.

“We had many challenges along the way,” Callas said. “When we first landed on Mars, one of the things that happened was we had a heater on the robotic arm on the rover that got stuck on. So every night that heater would come on and waste energy from the rover. If we left it alone like that, the mission wouldn’t have lasted long beyond the 90 days.

“So we developed this technique called deep sleep, which is every night we would turn everything off on the rover, including all the survival heaters, and the rover would get cold, but it would stay just warm enough that in the morning when the sun would come up, we would power everything back up,” he said. “It never got below its allowable temperatures.

“This is kind of like if you have a light in your bedroom stuck on, and you can’t sleep, so what you do is you go outside and you turn off the master breaker for your house,” Callas said. “But that means your refrigerator starts to warm up, but by the morning time when you wake up and you turn the breaker back on, the ice cream hasn’t melted too badly. And you do that every single night. Now imagine doing that for 5,000 nights. That’s what we had to do for this vehicle. But it also, partially perhaps, explains why we weren’t able to recover the rover.

If the rover’s batteries were fully depleted, its internal clock would have reset.

“With a loss of power, the clock in the rover gets scrambled, and it wouldn’t know when to deep sleep,” Callas said. “So it probably wasn’t sleeping at night when it needed to, and that heater was stuck on, draining away whatever energy the solar arrays were accumulating from the sun to charge those batteries. So that might be part of this explanation, in addition to the fact that now it’s much colder and darker on Mars (as winter approaches).”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.